The Growth of Portland

Before the railroad reached Puget Sound, nearly all trade from the Columbia Basin was channeled through Portland, the region's leading seaport and reputedly one of the wealthiest cities of its size on the West Coast. The building of the Northern Pacific to Portland and Puget Sound in 1883 and the extension of the Great Northern Railway to Everett and Seattle, Washington, a decade later boosted Seattle to a preeminent position.

Seattle’s emergence as a major urban center, however, did not diminish Portland’s aspirations. The city’s boosters were at one with the Oregonian, which observed in 1888 that Portland was the “Railroad Cross-Roads” of the Pacific Northwest, a place where great transport routes arrived as naturally as “the physical law which makes water run down hill.” Because of “the great natural channels” that led to the city, the Oregonian declared in 1890, every productive section of the Columbia region enjoyed a level route to Portland. To further the city's economic interests, boosters began promoting improvements in the Columbia River to provide “a deep and safe channel to the Sea.”

Developing Portland’s transportation infrastructure included more than railroad connections. The city completed the Morrison Bridge across the Willamette River in 1885 to reduce Portland’s reliance on the numerous ferries that plied the waterway. At the outset of the 1890s, the city built an electrical transmission line to Portland from the Willamette River Falls at Oregon City to power streetcars. Portland also invested $6 million to build the first Bull Run Reservoir east of the city, to take advantage of the clear waters on the western slopes of the Cascades.

Beginning in the early 1870s, the city began acquiring lands in its western hills that would eventually become Washington and Forest Parks, the largest urban park system in the United States. In the spirit of civic promotion, Portland citizens initiated the annual Rose Festivals, a June celebration that has become the city’s signature event.

By the turn of the century, the city’s rival on Puget Sound had made the business community nervous, and local bankers and the Portland Board of Trade moved aggressively to reassert Portland’s position as the preeminent city in the Pacific Northwest. The result was the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, which ran from June 1 to October 15, 1905. The fair was a civic and commercial success. More than 1.5 million people entered the Exposition through paid admissions and another 900,000 through courtesy passes.

Around Guild’s Lake in northwest Portland, elaborately columned buildings sheltered exhibits from every American state and several foreign countries. The U.S. government appropriated $1.7 million for its building‚ located at the center of pools and fountains and radiating streets and walkways lined with roses. The two dozen Filipinos were on display as part of the entertainment. Described and housed as savages, the Igorrote tribal members were an example of new colonial attitudes in the United States in the early twentieth century. Native Americans were also featured as curiosities, and a bronze statue of Sacagawea was forged to celebrate the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Indian exhibit showcased assimilation efforts at schools like the Chemawa Indian School.

The Oregonian praised the Exposition for being “a great financial success” and for surpassing its planners’ expectations. A year after the event, the paper reported: “the Lewis and Clark Exposition officially marked the end of the old and the beginning of the new Oregon.” The Exposition helped boost the city’s population from 90,000 to 207,000 between 1900 and 1910; during the same period, the state’s population increased by 70 percent.

Following the Exposition, the Portland Board of Trade and its successors continued to push railroad extensions to Oregon’s hinterland, proposals that the business community believed would benefit the city. When rumors surfaced that the Southern Pacific Railroad planned to build a line north to Klamath Falls, the Oregonian worried that the route would “drain away to California the rich and rapidly growing traffic of the Klamath country.”

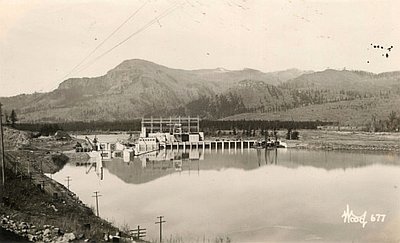

The newspaper took a different view a few years later when the Southern Pacific announced that it would build a rail line from Eugene to Coos Bay, a prospect that would enable Portland to benefit from trade that otherwise would be lost to San Francisco. Chamber of Commerce publications also promoted efforts to improve navigation on the Columbia River, proposals that included deepening the river and the shipping channel to the Portland Harbor and building a canal between The Dalles and Celilo Falls. The Portland business community and upriver shippers argued that improving Columbia River navigation would develop the hinterland and advance the city’s prospects as a trading center. Laborers on improvement projects such as the Cascades Canal included Chinese, who were paid 85 cents a day, significantly less than the $1.75 their white counterparts earned.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

The Igorrote [sic] Tribe from the Philippines

This article was published in the Lewis and Clark Journal in October 1905. It discusses the exhibition of Igorot people at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition and …

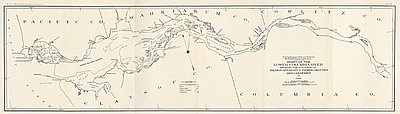

Chart of the Lower Columbia River

This map was published in an 1894 report by the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries. It shows the distribution of canneries and fishing gear by type in …

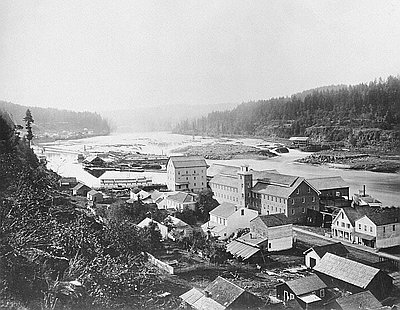

Oregon City and Willamette Falls

This 1867 photograph, taken by Carleton Eugene Watkins, shows Oregon City and the Willamette Falls soon after the first portage railroad was built there. Oregon City had been incorporated …