A New Legal Landscape

Joel Palmer (1810-1881)

The presence of Americans to the Oregon Country in the early 1840s led to a new legal landscape, imposed first in the Willamette Valley and then to other areas. The earliest Euro-American settlers in the valley—French Canadians, retired Hudson’s Bay Company personnel, and people associated with the Methodist mission—held land through simple preemption and occupation. HBC officials feared that the growing number of Americans would form a colony on the lower Columbia, and they began a search for legal mechanisms to protect existing land claims.

Forewarned that a large group of emigrants would arrive in the Oregon Country in the fall of 1843, Euro-American residents came together in a series of meetings in the spring and early summer. They created the Provisional Government, which existed independently of both the United States and Great Britain. Article 3 of its Organic Code established the basis for landownership: “No individual shall be allowed to hold a claim of more than a square mile, of 640 acres in a square or oblong form, according to the natural situation of the premises; nor shall any individual be allowed to hold more than one claim at the time.”

In addition, “every free male descendant of a white man who has resided in the territory for 6 months” would be a citizen, which enfranchised the sons of white males with Indian wives. The newly adopted legal principles also prohibited slavery, although they required all African Americans to leave the territory within three years. The territory’s first exclusion law passed three years later, making it illegal for any Blacks to reside in Oregon.

In 1846, a treaty between the United States and Great Britain established a national boundary along the forty-ninth parallel, exclusive of the southern tip of Vancouver Island, which remained in Canada. With beaver largely trapped out south of the Columbia River, the influential HBC did not pressure the British to strike a more favorable agreement. The company had already moved its Columbia Department headquarters from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island.

Settlement of the boundary issue left law and governance to the Provisional Government. The issue of territorial status for the American Northwest remained in limbo, as the slavery issue delayed congressional action to create a new territory. Congress finally took action following the attack on the Whitman Mission in November 1847, when Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and eleven others were killed. The Oregon Territorial Act, passed in 1848, prohibited slavery by acknowledging an anti-slavery section of the Ordinance of 1787. The act simply ignored the Provisional Government’s generous land-law arrangements.

Slavery and race were more than academic issues in early Oregon. While many Oregon Trail emigrants were from slave-holding or border states, the great majority did not own slaves and did not belong to the slave-holding class. That said, most of them carried cultural baggage that included deeply held prejudices against African Americans, and a small number traveled to Oregon with their human chattel. Hundreds of free Blacks, some of them fleeing racial riots in the North, also migrated west on the Oregon Trail before the Civil War; most did not end up in Oregon because of the territory’s exclusion laws.

In 1844, the Provisional Government passed the first exclusion law in Oregon, which directed that any free Black would be whipped and expelled from the territory. That law was soon amended, substituting hard labor for whipping, and was repealed in 1845 before it went into effect. Another exclusion law was passed in 1849, applied to any new immigration of Blacks to the territory; that law was repealed in 1854.

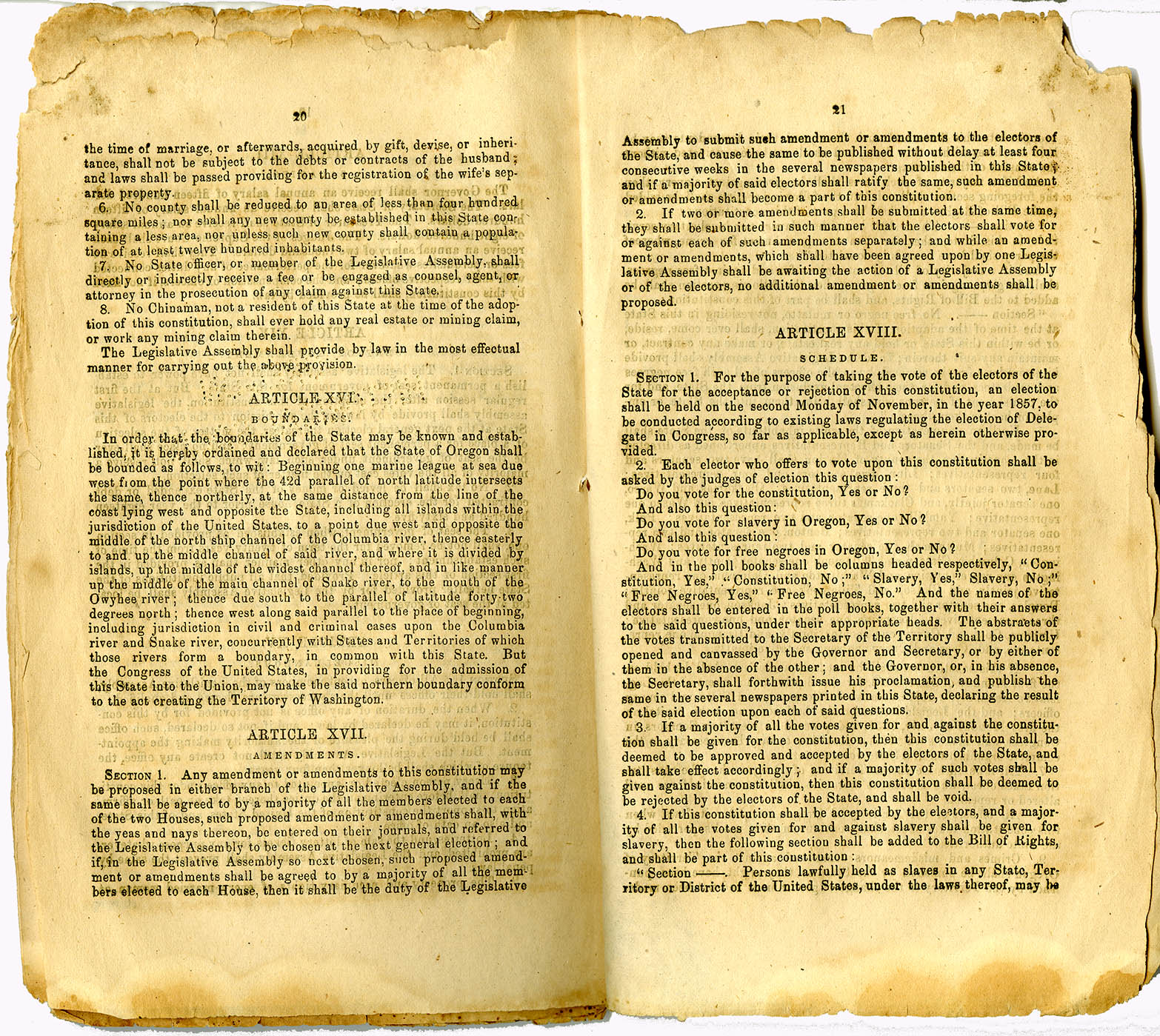

Statehood initiatives in Oregon were defeated three times before voters successfully called for a constitutional convention in June 1857. Then, on November 9, 1857, the new state constitution went before voters. Oregon Territory’s electorate—all white males—voted in favor of the constitution (7,195 to 3,195), against slavery (7,727 to 2,645), and in favor of excluding African Americans (8,640 to 1,081). The constitution was ratified by Congress on February 12, 1859, and signed by President James Buchanan two days later.

There was nothing particularly innovative in the state’s founding constitutional charter, and most of its legal principles were modeled after the constitutions of Indiana, Iowa, and Michigan. One distinction was that Oregon was the first state admitted to the Union with an exclusion clause against African Americans. The state did not eliminate that provision from the constitution until a successful referendum passed in 1926; additional racist language was not removed until 2001.

The race question was also part of the single-most important piece of land legislation to permanently inscribe itself on the Oregon landscape. Because the territorial legislature in 1848 said nothing about the existing land situation, Willamette Valley settlers commissioned their elected territorial delegate, Samuel Thurston, to secure the passage of a federal law that would legitimate existing land claims in Oregon. The problem for Congress—which traditionally had been tied to 160-acre grants—was the size of the Provisional Government claims of 640 acres.

Thurston achieved remarkable success when Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law in September 1850. With some modifications, the act recognized the Provisional Government’s claims of 640 acres. For settlers in Oregon, white male citizens were eligible to hold 320 acres. If a man was married, his wife could claim an additional 320 acres in her own right. For citizens arriving after 1850, the acreage limitation was halved to 320 acres for a married couple. To gain title, a person had to live on and make improvements to a claim for four years. Section 4 of the law established eligibility: the land was “granted to every white settler or occupant of the public lands, American half-breed Indians included, above the age of 18 years, being a citizen of the United States, or having made a declaration according to law, of his intention to become a citizen.”

The Oregon Donation Land Law benefited incoming whites and dispossessed Native people; it also prevented African Americans and Hawai’ians from owning land. Approximately a thousand indigenous Hawai’ians traveled to the Pacific Northwest between 1787 and 1898, when the islands were incorporated into the United States, working primarily in the fur trade for the Pacific Fur Company, HBC, and other enterprises.

In his lobbying efforts, Thurston informed Congress that the “first prerequisite step” to settling the land issue was the removal of Indians. To meet constitutional requirements, he advised, Indian title to land had to be extinguished before it could become part of the public domain. Moreover, the Oregon Territorial Act guaranteed Indians rights to their homelands “so long as such rights shall remain unextinguished by treaty between the United States and such Indians.”

Before debating the law, Congress authorized the appointment of commissioners to negotiate treaties with Oregon tribes “for the Extinguishment of their claims to lands lying west of the Cascade Mountains.” The commissioners were empowered to negotiate treaties, “and if they find it practicable, they shall remove all these small tribes and leave the whole of the most desirable portion open to white settlers.”

By expropriating Indian land through the treaty process, much of Oregon was made part of the public domain and was available to settlers under federal land laws. In brief, the Oregon Donation Land Law validated white settlers’ claims in the Willamette Valley and brought a rush of people into the Umpqua and Rogue valleys. Before the law lapsed in 1855, 25,000 to 30,000 people had entered the Oregon Territory, a population increase of close to 300 percent. Seven thousand of them made claims to 2.5 million acres of land. Until the 1870s, the law had a greater influence in shaping the course of Oregon history than any other event or piece of legislation.

By attracting large numbers of settlers to the Umpqua and Rogue valleys, the Oregon Donation Land Law helped trigger something akin to a race war. Prospecting miners working the tributaries of the Rogue River joined with white settler-farmers to drive the Rogue Indians from their gathering grounds, forcing their removal after a series of bloody hunt-and-destroy forays. For Native people in the Willamette, Rogue, and Umpqua valleys, the 1850s proved tragic, eventually leading to their relocation to the Siletz and Grand Ronde reservations.

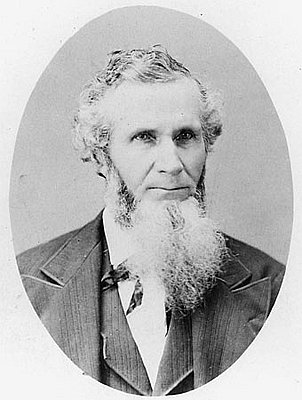

The two reservations were established by presidential executive order and were not subject to treaty stipulations. As a result, only a presidential decree was required to open the lands to settlement. The architect of the coastal reservations was Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer. He argued that the reserves were isolated and distant from the Willamette Valley and the ocean and that they lacked agricultural potential. The establishment of the reservations effectively marginalized these peoples, further limiting their access to traditional hunting and gathering locations and threatening their way of life. The removal policy opened millions of acres to market forces under federal land laws—and eventually into private, non-Indian ownership.

Confined to reservations and suffering the persisting ravages of disease, Native populations continued to spiral downward. Those whose homelands were the interior Rogue and Umpqua valleys found the coastal reservation wet and cold and lacking in traditional food sources. Because the Indian Bureau failed to provide adequate food and shelter, the reservation brought suffering, starvation, and disease to those who lived there. Until the early twentieth century, annual deaths on the Siletz and Grand Ronde reservations exceeded birth rates. The decreasing numbers offer striking testimony to the inhumanity of reservation policy: the number of enrolled members of the Siletz Reservation dropped from 2,026 in 1856 to 438 in 1900; at Grand Ronde, the population declined from 1,826 in 1857 to 298 in 1902.

Before reservations were established, some Native people worked in the non-Indian economy. As early as the 1860s, people began taking seasonal leaves from reservations as a kind of migratory work force in the Willamette Valley agricultural fields and in Portland’s small service sector.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

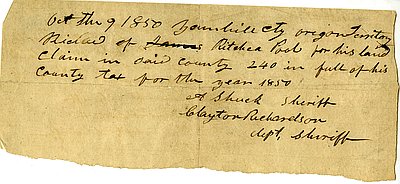

Related Historical Records

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad …

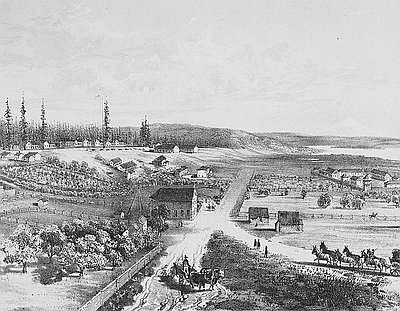

Settlers to Siletz Reservation Agent Fairchild

This letter is indicative of the hostility that some early settlers had for Native people. A band of Athapaskan Indians, known as the Kwatami, lived near the Sixes …

Debate Over Oregon Constitution

This document is an excerpt from a speech by Missouri congressman John B. Clarke in the U.S. House of Representatives supporting the admission of Oregon. He outlines the main objections …