Oregon’s Political Landscape

The Civil War and the Republican Party’s rise to power and influence shaped Oregon’s political landscape between 1860 and 1920. The legislature ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which prohibited slavery, in 1865, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship to all American-born people, in 1866. A revitalized Democratic Party made a futile gesture to rescind the state’s approval of the Fourteenth Amendment in an Oregon Senate resolution in 1868.

Although a majority of Oregonians voted for Republican Party candidates in every presidential election between 1872 and 1908, the two major parties traded gubernatorial elections and contests for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives for much of the second half of the nineteenth century. Beginning in 1880, Republicans began a long period of dominating the state legislature, controlling the state House of Representatives until 1935 and the state Senate until 1957. But Oregon’s political culture was more complex than electoral contests between Democrats and Republicans, especially during periods of economic depression.

When the national and regional economy floundered in 1873 and the mid 1880s, and then descended into even greater turmoil during the depression of the 1890s, rural and urban protesters and reformers challenged conventional politics. The woman’s suffrage movement added to those activities in Oregon, especially through the influence of writer and reformer Abigail Scott Duniway. Beginning in the early 1870s and for the next forty years, Duniway worked with local and national suffrage leaders, including Esther Pohl Lovejoy and Emma Smith DeVoe, in the struggle to achieve rights to property and the vote. For much of that time, she battled her powerful brother, Harvey W. Scott, editor and publisher of the Oregonian. From 1871 to 1887, Duniway published the New Northwest, a newspaper devoted to the suffrage cause.

Oregon farmers also joined forces, responding to charges that local merchants were colluding with the O&C Railroad to unfairly raise shipping rates. They organized chapters of the Grange (Patrons of Husbandry) in the western valleys and issued calls for an independent congressional candidate who would promote Oregon’s agricultural interests. With the rural economy suffering through the mid 1870s, farmers succeeded in getting their candidates elected to county offices.

Temperance societies also proliferated during the 1870s, occasionally joining forces with anti-monopoly organizations to push for the prohibition of alcohol, restructured tax policies, and railroad regulations. With another economic downturn in the mid 1880s, these diverse reform factions coalesced into a powerful statewide insurgency.

The social and political turmoil in Oregon was linked directly to events, circumstances, and economic conditions elsewhere in the United States. The Knights of Labor affiliate in Portland, for example, followed the precepts of the national organization: “To secure the toilers a proper share of the wealth they create.” Although Grange membership declined nationally, Oregon had 86 chapters, with 3,140 members in 1890.

State chapters of the Farmers Alliances had been active during the 1880s, providing a forum for rural discontent in the state. Although Oregon and Washington Alliances differed in their ideological approaches, both found the power of trusts and corporations intolerable and sharply criticized the developing land-fraud cases. High railroad rates, heavy taxes on farmland, and a short money supply filled out their list of grievances. Because they represented a broad spectrum of Oregon’s male voters, prohibitionists used the reform agenda to promote their own ends.

Grangers, prohibitionists, the Union Labor Party, and Oregon affiliates of the Knights of Labor convened in Salem in 1889 to address common grievances: “The power of the saloon in politics is continually increasing….The power of the trusts and corporations has become an intolerable tyranny, the encroachments of landgrabbers have almost exhausted the public domain, and the corruption of the ballot box has rendered our elections little less than a disgraceful force.”

The convention and subsequent meetings led to the formation of the Union Party, the predecessor to the People’s Party of Oregon. Democratic governor Sylvester Pennoyer gained the backing of the Union Party when he supported the secret ballot and an investigation of the Oregon Land Board during his second successful campaign for governor in 1890. By the time the People’s Party (also known as the Populist Party) was formally organized in 1892, a merger of the Farmers’ Alliance and the Knights of Labor, Pennoyer had become Populist.

The most influential voice for Oregon Populism and the early twentieth-century reforms known as the Oregon System was lawyer William S. U’Ren, who served one term in the legislature (1897-1898). Between 1902 and 1908, U’Ren and his People’s Power League would push through a remarkable series of measures designed to remove corruption from the political process.

The Populists’ Omaha Platform, which they called “The Second Declaration of Independence,” served as a catalyst for Oregon’s reform groups, who found much to their liking in the manifesto of the new People’s Party: (1) the free and unlimited coinage of silver; (2) government ownership of railroads; (3) returning railroad and other land grants to the public domain; and (4) political reforms such as the secret ballot, the initiative and referendum, and the direct election of U.S. senators.

Populists formed organizations across the state. In the fall of 1892, Kansas firebrand Mary Ellen (Elizabeth) Lease, whose slogan was “Raise less corn and more hell,” campaigned for the national ticket in Portland with Abigail Scott Duniway. In the wake of the national industrial depression, Oregon voters elected four Populists to the legislature in 1893 and ten in 1895. The strength of the People’s Party in Oregon and elsewhere was in rural areas.

Political ferment of another kind was brewing as information was leaked to the public about the fraudulent use of federal land policies. Oregon was at the center of a national inquiry in the early twentieth century, with much of the attention focused on the manner in which the legislature disposed of the state’s land grant. The legislature directed the State Land Board to dispose of its “school lands” for $1.25 an acre, a practice that invited wholesale fraud because the lands in question were unsurveyed and state and federal land offices were overburdened with work.

When the land-ring scandals broke in 1903, the most valuable of the state’s timberland had already passed into private ownership. Governors William Lord (1895-1899) and T.T. Geer (1899-1903) were aware of the fraudulent practices but argued that legislative policy hampered the State Land Board in properly managing the grant. Federal policies, too, were subject to widespread dishonesty, especially those associated with disposing of railroad and wagon-road land grants.

The looming federal land-fraud debacle helped elect Democrat George Chamberlain to the governorship in 1902. Oswald West, the new land agent, completed an investigation of the land ring in 1905 and delivered a report that led to the trial of several perpetrators who were convicted of fraud and conspiracy. Those convicted included Oregon Congressman John N. Williamson (whose conviction was later overturned) and the state’s longtime United States senator, John H. Mitchell.

George Chamberlain’s election as governor in 1902 and the emergence of Oswald West as a reformer marked a new direction in Oregon politics. As governor from 1903 to 1909, Chamberlain supported the Oregon System’s reforms: the initiative, referendum, and recall and the direct election of U.S. senators. He also backed the conservation policies of President Theodore Roosevelt and the nation’s chief forester, Gifford Pinchot. Chamberlain pushed other Progressive Era measures through the legislature, including prison reform, state railway and library commissions, and a child labor law.

After Chamberlain’s election to the U.S. Senate in 1909, voters elevated Democrat Oswald West to the governor’s office in 1910. With the exception of Tom McCall (1967-1975), no Oregon governor has enjoyed a more favorable historical reputation. A progressive reformer, West was courageous and seemingly willing to take on all comers. During the 1911 legislative session, for example, he faced off against a Republican-dominated legislature and vetoed sixty-three bills.

Although Republicans controlled the 1913 legislative session as well, West was successful in advancing his own legislation, including tougher banking regulations, protections against fraudulent securities, reform of the state’s railroad commission, modernized state budgeting policies, a minimum wage law, and a workmen’s compensation system and Industrial Accident Commission. In 1913, in his biennial message to the legislature, West insisted that Oregon’s beaches be declared a public highway, accessible to all citizens. Within a month, the legislature had approved a bill to that effect.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

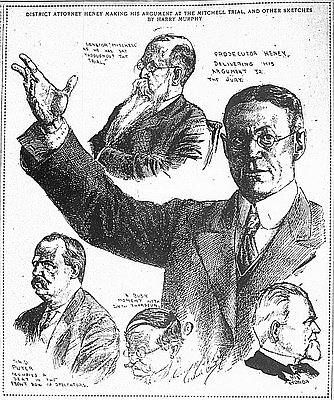

Land Fraud Trial of Senator John Mitchell

This sketch by Harry Murphy was published in the Oregonian on June 29, 1905. It shows United States District Attorney Francis J. Heney making an argument in the …

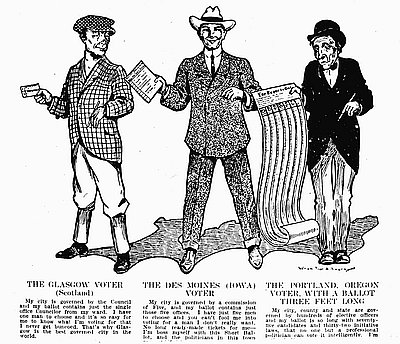

Oregon System Cartoon

This political cartoon from Joseph Gaston’s Centennial History of Oregon depicts a befuddled Portland voter holding a lengthy ballot in one hand standing next to two other men …

Oregon Cavalry Volunteers Uniform

This uniform, belonging to Col. Thomas R. Cornelius of Company “D,” First Regiment in the Oregon Cavalry Volunteers, is representative of those worn by soldiers in the Union …