Charles McNary, a Republican with Progressive Credentials

Oregon’s most important political figure during the first half of the twentieth century was Salem-born Charles McNary, whose political ideology bridged William U’Ren’s direct-legislation reform measures and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. Educated at Stanford University, McNary served as dean of Willamette University’s law school and was on the Oregon supreme court, where he gained a reputation for writing legal opinions upholding the state's Progressive reform measures.

When Senator Harry Lane died in the spring of 1917, Governor James Withycombe appointed McNary to the U.S. Senate. In the general election, he survived a tough primary campaign against a conservative Republican and defeated his Democratic opponent and friend Oswald West, garnering over 54 percent of the vote. Labor unions, the Farmers’ Union, the Grange, and remnants of the Progressive Party provided important support in his successful campaign.

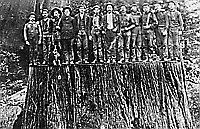

McNary spoke for prominent political and development groups in the Pacific Northwest, especially the region’s powerful lumber industry. Although he billed himself as a Teddy Roosevelt conservationist, McNary effectively opposed efforts by Gifford Pinchot and others to impose federal regulations on private forestry practices. With New York Congressman John D. Clarke, he co-sponsored the most significant piece of forestry legislation in the first half of the twentieth century.

Passed in 1924 and signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge, the Clarke-McNary Act made federal aid available to states for fire prevention on all classes of land. The act also included provisions for reforestation work and set aside funds to purchase cutover lands for the national forest system. The lumber industry praised the act for its cooperative principles and for avoiding the federal regulation of harvesting practices. McNary also cosponsored the McSweeney-McNary Act in 1928, an initiative that authorized federal support for a wide array of forest research programs.

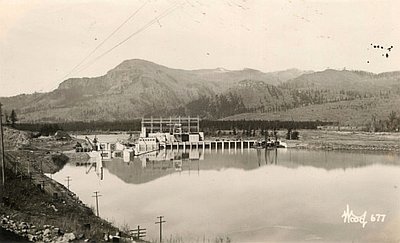

Along with influential senators from Washington State, McNary consistently supported Columbia River development projects. As Republican minority leader of the Democrat-controlled Senate in 1933, McNary urged President Franklin D. Roosevelt to support the building of Bonneville Dam on the lower Columbia. Such a dam, he told the president, “would mark the first step in the complete utilization of this great river for navigation, flood control and erosion with a wholesome quantity of electrical power as an incident thereto.”

McNary was also an early supporter of the multipurpose dams on the Willamette River system. In 1935, he joined Washington senators Homer Bone and Lewis Schwellenbach in calling for a high dam at Grand Coulee to maximize the production of inexpensive public hydropower. In his so-called secret diaries, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes credited McNary with being the leading force behind the Columbia River projects.

Some historians argue that Charles McNary should be best remembered for his sponsorship of farm-relief legislation, which was designed to alleviate depressed prices in the agricultural sector during the 1920s. The McNary-Haugen bills called for the federal government to purchase surplus agricultural commodities and to set price supports for domestic and international sales. The Wall Street Journal dubbed the McNary-Haugen measures “an unwise experiment in socialism and government price-fixing.”

The issue became a factor in the Republican presidential primaries in 1924, when California’s senator Hiram Johnson backed the McNary-Haugen idea in his effort to unseat President Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge won the primary and the general election and then appointed a secretary of agriculture who opposed McNary-Haugen. Congress finally passed a McNary-Haugen bill in 1927 only to have the president veto the measure in a sharply worded message. When Congress forwarded a slightly modified bill the following year, Coolidge again used his veto power. The principle of government price supports would surface again during the Great Depression in the form of several New Deal reform proposals.

As Senate minority leader, Charles McNary enjoyed cordial relations with Franklin Roosevelt. He helped push through the most famous schedule of reform legislation in American history, supporting the creation of the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and the Farm Credit Administration (FCA) because they created public works jobs and provided support for beleaguered farmers.

The Oregon senator also got along well with key Roosevelt officials, including Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and Secretary of the Interior Ickes, and he was a key supporter of the New Deal’s most enduring legacy, the Social Security Act of 1935. In Oregon, however, McNary barely survived a challenge by radical Democrat Willis E. Mahoney in the 1936 election. Although he remained mute about the Republican presidential candidate, Kansas Governor Alf Landon, McNary squeaked through with a plurality of 5,510 votes. It was clear that the Roosevelt landslide in 1936 had made it difficult to elect a Republican.

Although his key legislative achievements were behind him, the ambitious McNary remained at the center of national Republican politics. During the midterm elections in 1938, he believed that divisiveness in the Democratic Party offered Republicans an opportunity to reclaim some congressional seats. McNary’s predictions proved accurate when Republicans won eight senatorial races and regained eighty-one House seats. Two years later, he sought the Republican presidential nomination, but his reputation during the 1930s as an isolationist hurt his prospects. In the midst of the growing international crisis, he accepted the vice-presidential nomination on the Wendell Wilkie ticket in 1940. With war heating up in both Europe and Asia, Roosevelt easily prevailed in his unprecedented third run for the presidency.

McNary supported most of the administration’s war preparation measures. When President Roosevelt signed the declaration of war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, McNary, then Senate minority leader, stood directly behind him. The president offered McNary a Supreme Court seat early in the war, but the Oregonian turned him down.

As the Allies began to prevail in Europe and the Pacific, McNary worked with the Roosevelt Administration to shape a strategy for the postwar era. His work was cut short when he became ill from a brain tumor in the fall of 1943. McNary served in the Senate until his death in February 1944, a remarkably productive twenty-six years in which he practiced the nonpartisan politics that earned him great popularity in his home state.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

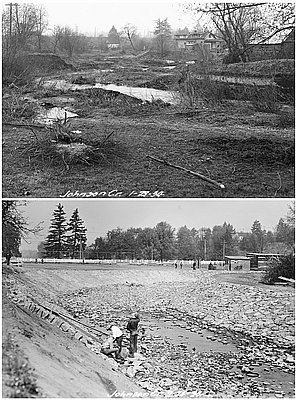

Johnson Creek Flood Control

These photographs show two contrasting views of Johnson Creek. The top photograph, dated January 29, 1934, was taken just prior to the start of flood control work on …

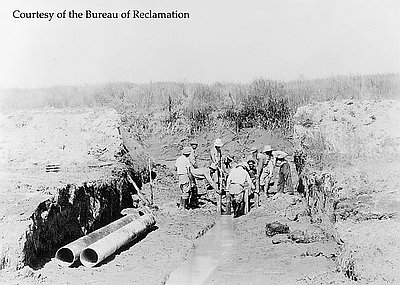

Laborers on the Klamath Project

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a New Deal program proposed in 1933 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide jobs for unemployed Americans during the Depression. This …

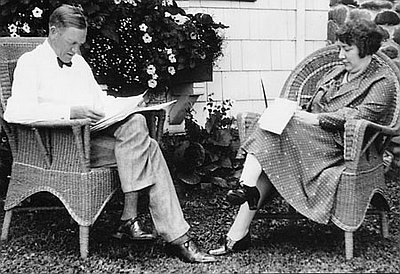

Charles McNary

1874-1944 Charles Linza McNary was not considered much of a campaigner. He gave one or two speeches when he ran for office, preferring to spend the campaign season …