A Framework for Learning

The non-Indian educational systems in the Pacific Northwest began with the Hudson’s Bay Company and New Englander John Ball, who taught the children of fur trappers who frequented Fort Vancouver. The missionary schools established during the 1830s signaled the first American effort. The Methodists’ Willamette Mission, an enterprise of the ecumenical American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and more than two dozen Roman Catholic ventures (Franciscans and Jesuits) extended educational activity and religious proselytizing throughout the region.

Those early influences helped shape Oregon’s educational system through the turn of the twentieth century, with nearly thirty parochial schools operating across the state by the early 1880s. In addition, many of the region’s universities and colleges were rooted in Christian precepts, including the Oregon Institute (present-day Willamette University) founded in 1842 as part of the Methodist Mission and Pacific University in Forest Grove founded in 1849 by members of the Congregational Church.

Oregon’s public schools also owe their beginnings to missionary influences, especially in the person of Rev. George Atkinson, who wrote Oregon Territory’s first school law in 1849. Reflecting the chief characteristics of New England educational systems, the territory’s organic school legislation included these principles: (1) education should be free; (2) control should be decentralized and local; (3) a permanent school fund should be established; (4) professional standards should be established to provide for the certification of teachers; (5) schools should be tax-supported; and (6) educational institutions should practice religious freedom. Except for its inspirational objectives, the legislation had little effect, and Oregon’s public education would show little improvement for more than twenty years.

The Oregon Constitution, which Congress approved in 1859, chartered the fundamental body of school law that has guided public education in the state every since. Embodying the principle of free public schools, Article 8 declared that the governor would serve as superintendent of public instruction for the five years, after which the legislature would create a position for an elected superintendent with specified powers and responsibilities. In addition, “the Legislative Assembly shall provide by law for the establishment of a uniform and general system of Common schools.”/

Article 8 also mandated that all proceeds from the state’s school lands be used for educational purposes and that the State Land Board—composed of the governor, the secretary of state, and the state treasurer—“shall manage lands under its jurisdiction with the intent of obtaining the greatest benefit for the people of this state.”

Some influential people in Oregon acted to obstruct the constitutional provisions that called for free public education for all school-age children. Oregon Statesman editor Asahel Bush, for example, wrote that common schools could not be justified because the state was too sparsely populated. Harvey W. Scott, the editor of the Oregonian from 1865 until his death in 1910, was outspoken in his opposition to free textbooks and warned of the evils of using tax money to support high schools. In lieu of financing such a “cumbrous and expensive system,” he wrote, parents who wanted to educate their children “beyond the common branches of the old fashioned common school should pay for it.”

Governor W.W. Thayer (1878-1882) believed that education beyond elementary school should focus on teaching students a trade, and Portland businessman William S. Ladd argued that public money should not be used to teach academic subjects. Populist governor Sylvester Pennoyer (1887-1895) insisted that public taxes should be used only to teach the three Rs (reading, writing, and arithmetic); and Simeon Reed, the chief benefactor of Reed College, thought children should be taught “useful industry” and kept in school for fewer hours.

Effective and comprehensive public-school education was not achieved in Oregon until the early twentieth century. High schools were established on a district-by-district basis from 1880 until 1901, when the state legislature mandated that all districts had to provide students a high school education. Oregon was little different from other states with similar geographic and demographic profiles: vast distances, lack of transportation, insufficient funding, insufficient school buildings, abbreviated school terms, and inadequate and shoddy equipment. There were also questions about low salaries paid to teachers, the absence of uniform instructional materials, and common standards for teacher certification. In matters of equity—that is, providing children in rich and poor districts with the same quality of education—there were no standards for employment, with district superintendents making most of the hires.

Teachers’ organizations and teacher training institutes led the effort to establish professional certification standards and improved teaching methods and to provide higher salaries and better textbooks. Although the legislature established the office of Superintendent of Public Instruction and a Board of Education in 1872, local districts did little to improve conditions for its teachers. The Oregon Teachers’ Monthly urged its members to organize unions to push the issue of improved salaries, and teachers’ groups influenced the change in the high school curricula from the classics to courses in history, trigonometry, physics, and the practical sciences.

During this period, Oregon’s private academies and parochial schools continued to flourish. Portland residents supported Roman Catholic, Protestant, Hebrew, and German schools that provided religious or language instruction to students. The Portland Academy and Female Seminary, originally established in 1854 as a Methodist institution, reopened in 1889 as the Portland Academy. The private school provided an advanced curriculum for the children of Portland’s elite, eventually offering courses equivalent to the first two years of college. According to historian E. Kimbark MacColl, the academy was one of the few social and cultural opportunities in Portland at the time. Boasting that wealth and status were the pathways to success, the Academy flourished until improvements in Portland’s public high schools began to siphon students away during World War I.

During the nineteenth century, Oregon’s denominational academies and colleges were obstacles to the establishment of tax-supported institutions of higher learning. Prominent Oregonians like Judge Matthew P. Deady initially opposed publicly supported colleges because of competition from private schools, and it was not until the 1870s that the legislature appropriated funds to establish a state university in Eugene. With contributions from local benefactors, the city constructed the University of Oregon’s first building, named Deady Hall after the judge who served as chairman of its board of regents. With a limited student enrollment, the university opened in the fall of 1876.

Oregon State University’s institutional lineage can be traced to Methodist Episcopal-supported Corvallis College, first incorporated in 1858. When the church relinquished control in 1885, the school became Oregon Agricultural College, the state's land-grant institution.

Western Oregon University in Monmouth has a similar story, beginning in 1855 as Bethel Institute operated by the Disciples of Christ north of Rickreall. The school merged with Christian College in 1864 to become Monmouth University. In 1883, it became the Oregon State Normal School, a publicly supported teacher-training academy. The Oregon Legislature later supported the establishment of additional normal schools, Southern Oregon University (1909) and Eastern Oregon University (1929).

Other colleges and universities in Oregon began as religious institutions. Linfield College was established in 1858 as the Baptist College of McMinnville. The school later expanded its focus from the liberal arts to the sciences, establishing the Linfield Research Institute and absorbing the Good Samaritan School of Nursing in Portland. In 1891, the Methodist Episcopal Church founded Portland University, which operated until 1900. The Archdiocese of Portland purchased the abandoned school facility and surrounding acreage, establishing Columbia University, later renamed the University of Portland. Prior to the university becoming co-educational in 1951, Marylhurst University (1893) was the only Catholic school of higher learning open to women in Oregon.

Oregon Health & Science University, the state’s only academic health center, began as a small medical school in Salem. When Willamette University faculty organized a medical department in 1867, it became the first in the Pacific Northwest. In 1887, the University of Oregon established a rival school. The two schools merged in 1913. In 1974, the medical school united with schools of dentistry and nursing to become the University of Oregon Health Sciences Center. It was renamed Oregon Health & Science University in 2001, after merging with the Oregon Graduate Institute.

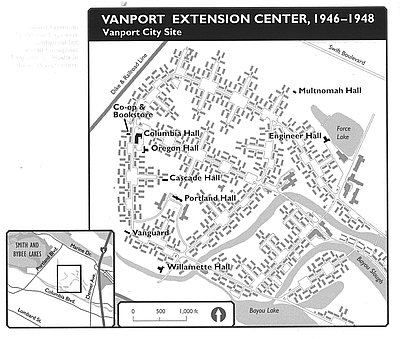

Oregon Institute of Technology, the only public institute of its kind in the state, was established in Klamath Falls in 1947. The school was created, in part, to help returning veterans reintegrate into a peacetime economy. During its first year, veterans comprised 98 percent of the student enrollment. The institution that became Portland State University also had high veteran enrollment during its first years. Established in 1946 as the Vanport Extension Center, it was organized to help relieve the state’s colleges by accepting the increasing numbers of veterans who took advantage of the GI Bill. When a flood destroyed Vanport in 1948, the school moved to Portland. In 1955, it became a four-year college, the first publicly supported institution of higher learning in the city.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Central School

Civic leaders demonstrated their commitment to an educated populace by opening Central School, shown here in 1858, and located originally at Southwest Sixth and Morrison. With tax dollars …

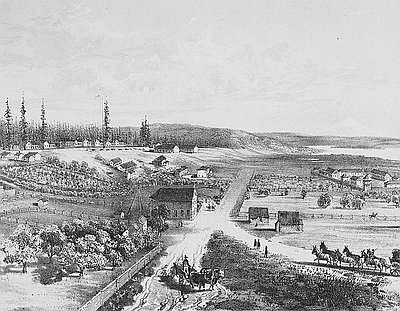

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad …

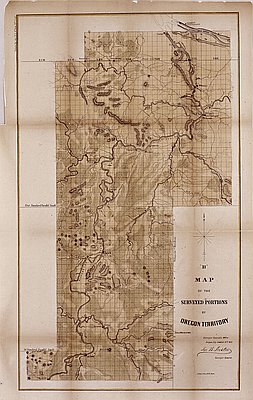

Surveyed Portions of the Oregon Territory, 1852

The map above shows the surveyed portion of the Oregon Territory as of October 21, 1852. It was prepared by John B. Preston, first surveyor general of Oregon. …