Resettlement

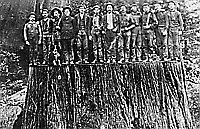

During the 1860s and 1870s, non-Indian migrants established a few small settlements across central and eastern Oregon. The gold-seekers were first, setting up camps in narrow canyons in the Blue Mountains. Because of the increasing demand for meat products, western valley stockgrowers began moving their herds of cattle and sheep east of the Cascades to graze on sage grasslands in the Deschutes, John Day, and Umatilla valleys.

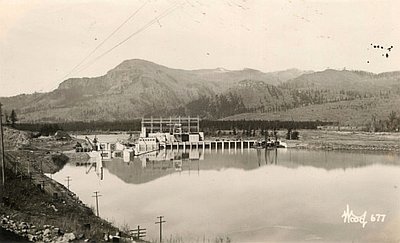

By the 1870s, cattle and sheep grazed across the region, with the largest and most spectacular herds in Oregon’s southeastern quadrant. For the upland areas south and east of the Columbia River—along the Deschutes–Umatilla Plateau—the era of range cattle was relatively brief. With the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad along the Columbia River in 1883 and the Oregon Short Line across northeastern Oregon the next year, the rolling hills of Sherman and Umatilla Counties were turned to wheat production. With sufficient seasonal precipitation during most years, the district’s loess soils were ideally suited to growing winter wheat. Within two decades, farmers had greatly expanded the area planted to wheat, establishing the single cash crop that continues to dominate the region's economy.

As farmers in the northern districts turned sage country to the plow, grazers increasingly concentrated their herds in more marginal areas, especially in the Harney Basin and the Malheur and lower Owyhee river valleys. The coming of the range-cattle industry to southeastern Oregon was tied to events in California, where the legislature enacted a series of herd and fence laws in the 1860s that sharply restricted access to the open range.

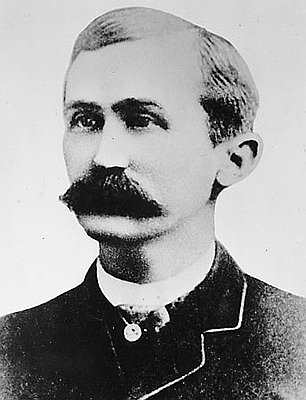

Two streams of people moved into the Harney Basin in the late 1860s: subsistence farmers from the Willamette Valley and California and cattlemen in search of reliable water and grasslands. Representing large corporate interests, foremen for the cattlemen staked out claims along streams that drained the northern and southern slopes of Steens Mountain. Through such methods, cattle barons such as Peter French and his California backer, Hugh Glenn, developed largely self-sufficient empires centered on controlling the few streams that emptied into the Harney Basin.

The rapidly growing livestock herds, including thousands of sheep driven into southeastern Oregon in the 1880s, brought systemic ecological change to the region. With the building of the Oregon Short Line along the Snake River in 1884, cattle interests shifted some of their sales to Huntington and Ontario, and ultimately to Chicago, rather than Winnemucca, Nevada, and the regional market in San Francisco. With the new rail line in place, livestock barons greatly increased the number of cattle grazed in southeastern Oregon.

Todhunter and Devine, for example, grazed 40,000 cattle; the French-Glenn and Thomas Overfelt operations had 30,000 head each; and Riley and Hardin had 25,000. These were speculative enterprises, designed to maximize profits at the lowest cost possible. In 1880, the federal census for agriculture identified the cattlemen’s monopoly on water supplies as the region’s major problem. By the turn of the century, a series of scientific surveys clearly indicated that the grazing practices of the large cattle interests were unsustainable.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.