The First Peoples

The places and stories that became Oregon had their beginnings amid cataclysmic volcanic eruptions, basalt lava flows, and powerful floods that shaped and reshaped the Columbia River landscape. The archaeological record places humans in Oregon sometime toward the close of the Pleistocene, a time when ice-age glaciers were retreating from the mountain interior of the Northwest. Archaeological finds in the Fort Rock area in central Oregon, The Dalles on the Columbia River, and on the Oregon Coast indicate that Homo sapiens were beginning to occupy several places in the region during the early Holocene epoch, from at least 12,000 years ago.

Scientific evidence demonstrates that Native Americans descended from Asian populations that migrated to North America by way of the Bering Land Bridge some 16,000 to 14,000 BP (before present). In 2008, archaeologists discovered human feces at the Paisley Cave in central Oregon, dating to approximately 12,300 BP. Additional early human evidence include dozens of sagebark sandals uncovered by University of Oregon archaeologist Luther Cressman in 1938 and later revealed to be more than 9,000 years old.

Indigenous peoples have another explanation for how people came to this place—origin stories that vary with place and circumstance and that usually involve supernatural forces. The Chinook people on the lower Columbia River, for example, tell several stories about the origin of their people. While chronicler James Swan was living in the Pacific Northwest, from 1852 to 1855, he recorded a number of stories the Chinooks told him. One involves an old man who is a giant and an old woman who is an ogress. When the old man catches a fish and attempts to cut it sideways, the woman cries out that he must cut the fish down the back. The man ignores her and cuts the fish crossways. The fish changes into a giant bird that flies toward Saddle Mountain on the northern Oregon Coast. The man and woman go in search of the bird. One day, while picking berries, the woman discovers a nest full of thunderbird eggs. As she begins to break the eggs, humans appear out of the broken shells.

In his work Coyote Was Going There: Indian Literature of the Oregon Country, Jarold Ramsey sharing a creation story from the Klamath Tribes describing the origins of Klamath country. The Klamath and Modoc creator Kamukamts floats on a great lake in a canoe and runs aground on top of the house of Pocket Gopher. While the two discuss who will become the elder brother, Gopher creates hills, mountains, fish, roots, and berries. Kamukamts names all the animals that will live on the land and walks around the earth selecting homes for the tribes. When Kamukamts sees smoke, Gopher admits defeat, declaring him the elder brother as the smoke comes from the people Kamukamts brought into being.

All Native peoples of Oregon have stories that describe how the world came to be—stories that have been passed from generation to generation. Some stories were recorded by anthropologists such as Franz Boas, whose 1894 Chinook Texts, for example, includes an account of Coyote transforming surf to land and learning how to fish.

By the sixteenth century, dozens of bands of people lived in present-day Oregon, with concentrated populations along the Columbia River, in the western valleys, and around coastal estuaries and inlets. Before 1750, according to ethnologist Melville Jacobs, the Pacific Northwest was home to approximately 200,000 people, who spoke sixty to seventy languages. In the interior valleys, especially east of the Cascade Range, people shared common language patterns across a large geographic area. The greatest linguistic diversity existed on the coast, where people spoke several languages, including Chinookan, Salishan, Siuslawan, and Athpaskan-Yeak. Northern Paiutes, who lived in what is now eastern Oregon, spoke languages in the Numic family,while Chinookan and Sahaptian speakers lived on the Columbia Plateau. The western interior was home to people who spoke languages that included Kalapuyan, Siuslawan, Molala, Takelman, and Klamath-Modoc.

People living in the Great Basin, the Columbia Plateau, and the valleys between the Coast and Cascade Ranges practiced a seasonal round, subsistence way of life, moving to specific locations throughout the year to harvest, process, and preserve particular plants and animals. In eastern Oregon, for example, the Wada Tika of the Northern Paiutes dug bitterroots and fished for salmon in the spring, hunted deer and elk in the summer, and gathered chokecherries in the fall. People on the coast did not have as extensive a seasonal round, relying on the abundance of food from the ocean. In winter, all people in present-day Oregon lived in permanent villages, which typically consisted of related families. Bands were composed of closely related villages that shared a common territory.

Because food sources were so abundant, coastal groups tended to live in fixed village sites, with some seasonal movement to upstream places to gather berries, camas, and other plants. The winters were relatively mild, and fish and shellfish were easily harvested from streams and estuaries. In the western interior valleys, a transition zone between the coast and the region east of the Cascades, people gathered roots, nuts, seeds, and berries that were available seasonally from the prairies, oak savannas, and foothills. They hunted deer, elk, and waterfowl and fished local streams for salmon and freshwater fish. In the interior plateau, people lived in fixed winter villages and followed seasonal rounds to gather plants and to fish and hunt. In the spring and fall, when salmon ran heavy in the Columbia River, bands came together at fishing places such as Celilo Falls, near present-day The Dalles. The people who lived in the basin and range country moved seasonally to favored fishing spots and hunting and gathering places. More than any other human group in early Oregon, people who lived in the High Desert had to travel considerable distances to good hunting and gathering sites.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Paiute Water Basket

The Paiute peoples of the Great Basin are widely known for their basketry, a fine example of which is shown above. This basket, probably made in the nineteenth …

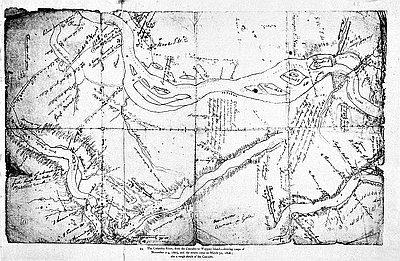

Columbia River from the Cascades to Wappato

This map, sketched by explorer Captain William Clark in early November 1805, shows the Columbia River between the Cascade Rapids and Sauvie Island — which Clark called “Wappato Island” …

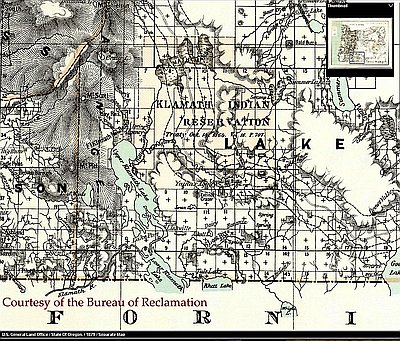

Klamath Indian Reservation

When white explorers entered the Klamath Basin in the 1820s, the Klamath Indians occupied the Upper Klamath Lake area, which included Klamath Marsh and the Sprague and Williamson …