- Catalog No. —

- Lewis & Clark Journal October, 1905

- Date —

- October, 1905

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Arts, Government, Law, and Politics, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Lewis and Clark Journal

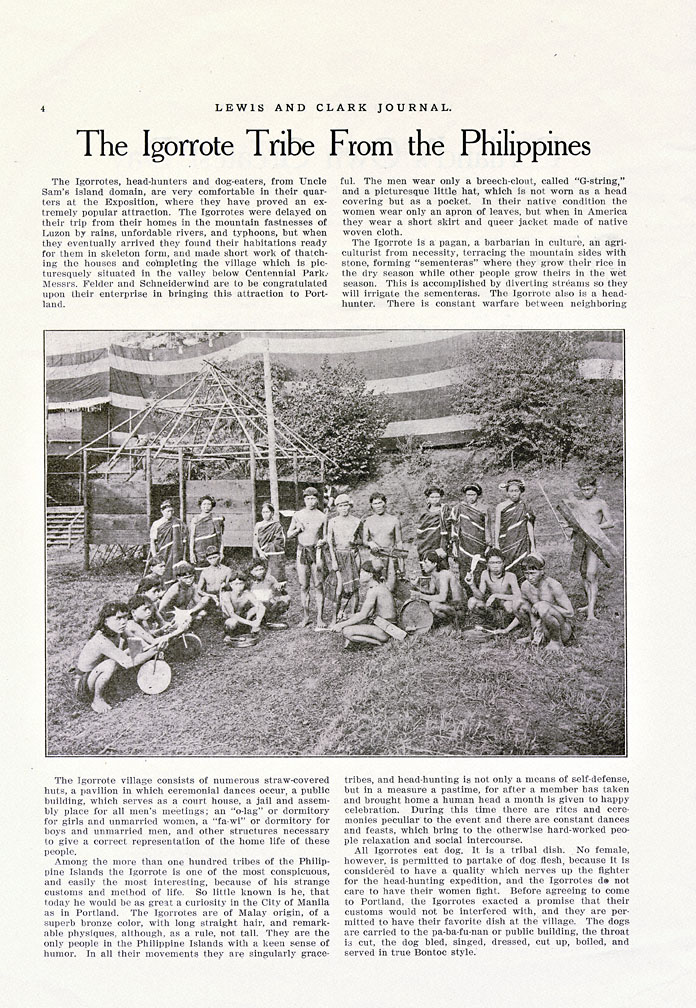

The Igorrote [sic] Tribe from the Philippines

This article was published in the Lewis and Clark Journal in October 1905. It discusses the exhibition of Igorot people at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition and Oriental Fair, held in Portland in 1905.

The term Igorot refers to a group of related village-based societies in the mountainous country of central and northern Luzon, the largest island in the Philippine archipelago. While most of the peoples of the Philippines are either Christian or Muslim, the Igorot practice a native religion often called “animism,” an anthropological term referring to the belief that spirits permeate the material world. Although Spain began colonizing the Philippines in the sixteenth century, the Igorot’s isolation in their mountainous homeland enabled them to maintain their cultural and political autonomy.

In February 1899, war broke out between American troops and Philippine independence fighters known as insurrectos. The Igorot sent a contingent of men to fight the Americans at Caloocan outside of Manila, but the Igorot warriors, armed only with spears, axes, and shields, quickly decided to return home when confronted with American rifles and artillery. The Igorot soon fell out with the insurrectos and became U.S. allies, acting as guides for American troops in the rugged highlands of northern Luzon.

Despite their rich history and sophisticated material culture, the Igorot have long been viewed as a “primitive” people, first by the Spanish and subsequently by the Americans. Indeed, beginning in 1898, all Filipinos were regularly depicted in newspapers and other media around the United States as racially inferior savages incapable of self-governance. The editors of the Oregonian, for example, argued that Filipinos were in a state of “race childhood”; they were “wild men” who only understood brute force. Arguments like these helped justify the often harsh repression of Filipinos who resisted American authority.

Exhibitions of Igorot peoples at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, and the 1909 Alaska-Yukon Pacific Exposition served largely to reinforce popular notions of Filipino inferiority. The displays stressed the “primitivism” of Igorot culture, particularly dog-eating, a common practice in many cultures, and head-hunting. Such practices functioned as gauges of the savagery of the newly conquered peoples of “Uncle Sam’s island domain.”

Further Reading:

Jenks, Albert E. The Bontoc Igorot. Manila: Bureau of Public Print, 1905.

Rydell, Robert W. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Related Historical Records

-

Filipinos Want Equal Rights or Independence

This letter by Filipino worker Ernesto A. Mangaoang was published in the Oregonian on September 21, 1931. Mangaoang describes the discrimination that Filipinos faced in Oregon during the …

-

News Editorial, The Filipinos and the War

This editorial appeared in the Oregonian on March 2, 1899. Titled “The Filipinos and the War,” it argues that one of the best ways to bring the Philippines …

-

Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair

One of Portland’s grandest parades started at the corner of Sixth and Montgomery streets at 10 a.m. on June 1, 1905. Mounted police led off, followed by marching …