Moving away from the Reservation

Through periods of war and peace, the federal government vigorously pursued its so-called civilization policies on northwestern Indian reservations. While the off-reservation boarding schools were the most obvious symbols of this effort, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) implemented other programs that intruded into Native cultural practices. The BIA considered Indian reservations to be laboratories of sorts, isolated settings where assimilation strategies would lead to cultural and linguistic change.

Reservation day schools, for example, prohibited students from speaking their Native languages or wearing Native dress, and they often required students to wear uniforms. At the Siletz Agency, the Indian Service operated both boarding and day schools until the boarding schools were discontinued in 1908; the reservation day school continued to operate for another ten years.

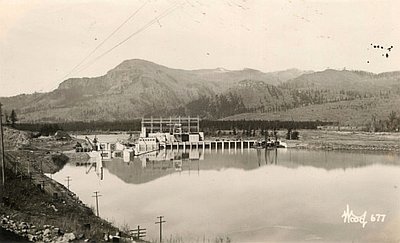

In reality, people who lived on coastal reservations went through a period of adaptation that had little relationship to federal Indian policy. Siletz people continued to work in local sawmills and logging camps, and some took seasonal cannery jobs at a salmon-processing plant on the lower Siletz River. As Siletz agricultural efforts declined after 1900, people left the reservation in search of wage-earning jobs. During World War I, seventeen Siletz men enlisted in the army; two of them were killed in battle.

The persisting effects of allotment policy continued to diminish the size of the old Siletz Reservation. A Lincoln County agricultural agent reported to a congressional inquiry in 1931 that land patents issued to individual Indians usually found their way into non-Indian hands: “a great deal of land was mortgaged and the mortgage sold, either foreclosed or directly sold. So from that time to the present time the better lands on the Siletz have passed out of the hands of the Indians.” The coup de grace to those developments was the Indian Bureau’s decision to close the Siletz Agency offices in 1925.

At the Grand Ronde Agency, the allotment policy had obliterated the original reservation land base, and only remnant plots of land remained: the tribal cemetery, lots for the Catholic Church, and agency buildings. To the south, when the Indian Bureau opened a short-lived agency in Roseburg in 1910, the office reported that three thousand Native people lived in southern Oregon. Some had taken allotments on the public domain, while others were pursuing seasonal wage work to support themselves.

Elsewhere in Oregon, the allotment program created checkerboard ownership patterns on the confederated tribal reservations at Umatilla and Warm Springs, with non-Indian lands mixed with tribal and individual trust lands. Over the years, many of the individual allotments were lost to non-Indian owners. Counties foreclosed on the Indian allotments for failure to pay taxes and sold the properties at public auction. Thousands of successful allotttees became landowners and citizens and assimilated into the dominant culture.

Until Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, Indians were not considered “citizens” unless they were individual property holders and paid taxes. In effect, the decade of the 1920s marked a period of transition in federal policy from the aggressive nineteenth-century assimilation efforts to the more benign programs initiated under the New Deal.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

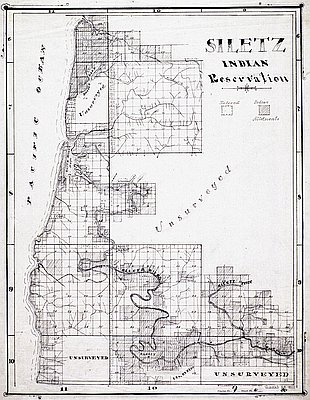

Siletz Indian Reservation, 1900

This map, produced by the Willamette Pulp and Paper Company, shows what remained of the Siletz Reservation in 1900. Each of the small squares on the map represents …

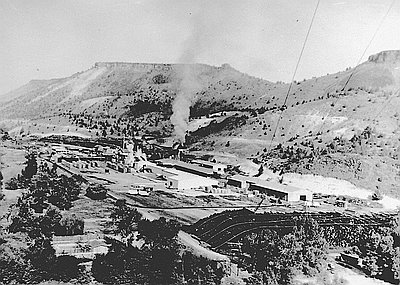

Warm Springs Reservation Mill

In 1938, four years after the congressional passage of the Indian Reorganization Act, the Warm Springs tribes became officially incorporated as the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs …