World War I marked a turnaround in what had been a prolonged period of depressed prices for lumber and agricultural products in Oregon. When Germany sent its armies to Belgium, British and French purchases of wheat and lumber sent prices soaring to three and four times their prewar marks. Much like farmers in other wheat-producing sections of the nation, those in Sherman and Umatilla Counties planted more acres to wheat and increased harvests during the war years than they had before.

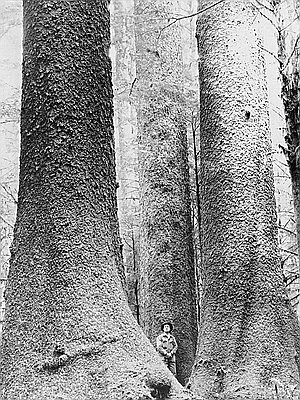

The lumber trade also expanded, especially in the production of wood structural materials for building army cantonments and milling spruce for airplane construction. The tough, lightweight, and straight-grained Sitka spruce was especially well suited for building aircraft wings. Spruce production ultimately became one of the more interesting stories to emerge from the war, involving for the first time federal intervention in the Northwest economy to produce an essential war commodity. With the creation of the United States Spruce Production Corporation, the government also became directly involved in controlling all aspects of the manufacturing process, including logging, milling, and labor relations.

By the 1920s, more people in Oregon were employed in the timber industry than any other single activity. Single male workers dominated the labor force into 1930s. Some employment opportunities had been available to women during World War I, though mainly piecework in mills, but they began to employ women as hourly wage earners by the 1920s. Women entered the timber industry in greater numbers during World War II, working in both the woods and the mills. During the 1940s, women occupied about one-third of the jobs in Northwest mills.

The timber industry attracted Japanese, Native American, and African American laborers as well. In Union County, the Mount Emily Labor Company hired Japanese and Indian workers, and the Oregon Lumber Company in Hood River employed many Japanese. Many ethnic workers faced racist attitudes and hostilities from white employees and employers, with some companies refusing to hire workers based on their race and ethnicity. In Maxville, a Bowman-Hicks Lumber company town, African American loggers and their families lived in segregated housing and attended segregated schools.

In 1925, white citizens forcibly removed Japanese sawmill laborers from the coastal town of Toledo. One worker later filed suit leading to the first guilty verdict for mob violence based on civil rights violations. The lawsuit, ruled on the following summer in the U.S. District Court of Oregon, established the rights of Japanese residents to choose their location of work and residence without fear of intimidation or expulsion./

Because Sitka spruce grows near the coast, most of the spruce harvests took place adjacent to Toledo, where the Spruce Production Corporation harvested nearly 54 million board feet. During the summer of 1918, 27,000 soldiers from the newly created Spruce Division were working in the camps and mills of western Oregon and Washington.

By the time the European war was nearing its bloody end, the Spruce Corporation was operating a Vancouver mill to manufacture wing beams, directing logging railroads and trucks, managing timberlands, and controlling other inventory—all valued at $24 million. When the war ended, the corporation liquidated its assets, which passed into the private sector. The C.D. Johnson Lumber Company, taking advantage of the government's generous terms, assumed ownership of the corporation's nearly completed mill in Toledo.

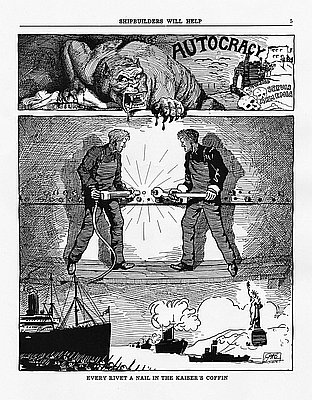

World War I also gave a great boost to the shipbuilding industry in the Pacific Northwest, primarily in the Seattle-Tacoma area, but a significant number of ships were constructed in Oregon. By the close of the war, the Emergency Fleet Corporation was operating twenty-eight yards, including plants in Tillamook, Astoria, Columbia City, and Portland. Because of war-related labor shortages, Idaho and Montana workers moved west to take jobs in the shipyards and other such industries. In their efforts to recruit an adequate workforce, companies offered higher wages and raided competitors for skilled workers.

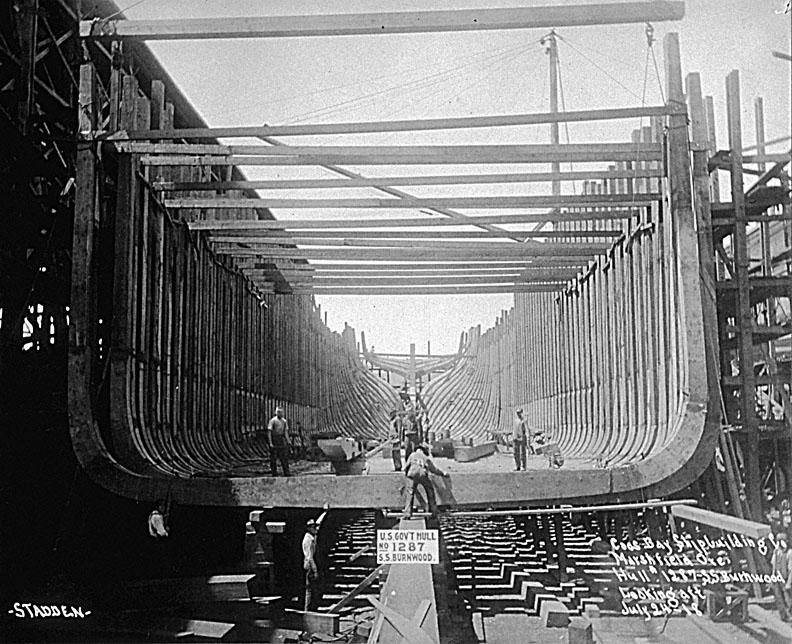

On Coos Bay, Emergency Fleet Corporation yards in Marshfield and North Bend dominated construction activity, operating with a full complement of carpenters and shipwrights, skills that were in high demand throughout the war. With the Armistice in November 1918 and the cancellation of shipbuilding and lumber orders, that frantic pace came to an end, and an army of the unemployed traveled together looking for work. The fallout from wage conflicts in Puget Sound shipyards led to the four-day Seattle General Strike in February 1919, when 60,000 workers walked off the job in solidarity with the shipbuilders. Seattle mayor Ole Hanson played on public fears that the day of revolution was at hand and became a national celebrity.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.