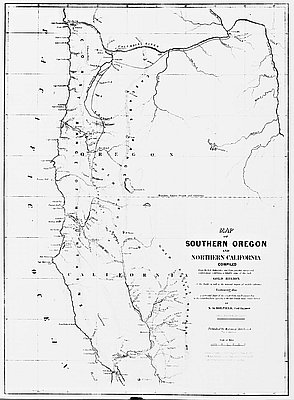

The California gold rush served as the great catalyst for Oregon agricultural growth and commercial development during and after the territorial period. The hundreds of thousands of people who flocked to the gold fields created an instant market for food and building materials, and miners who were working in the northern Sierras spilled over into the Rogue and Illinois valleys, further expanding that market.

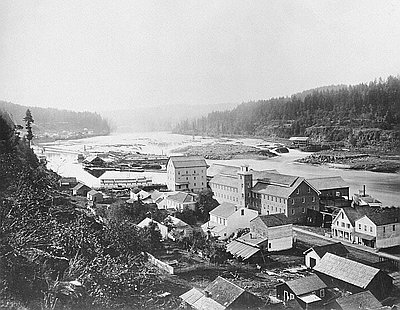

Scottsburg, at the head of tidewater on the Umpqua River, enjoyed a brief period as a jumping-off place for the southern Oregon mining country. Oregon City and Portland on the lower Willamette River developed a lumber and flour trade, with the number of ships entering tidewater multiplying several-fold in a brief period of time. Portland’s emergence as a leading trade center was directly tied to the booming California trade. The self-styled “stump town” enjoyed strategic advantages because of its location at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers, water routes that extended east and south into the interior and west to the Pacific. Portland had five commercial buildings in 1850 and more than forty by 1853, including four steam-powered sawmills.

To satisfy the demand for goods and materials, San Francisco capitalists ventured north to the sloughs and tidewater streams around the Coos Bay estuary and its Douglas-fir, Sitka spruce, and white cedar. With the construction of mostly California-owned mills during the 1850s, the Coos Bay area began a century-long role of providing lumber, coal, and other resources to the cities and towns in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although whites settled in small farms in low-lying areas around the Coos estuary, timber harvesting became the area’s bread-and-butter industry. During the next several decades, extensive waterways were turned into industrial transportation arterials to float log rafts to the big mills. Coos Bay also became the most timber-dependent place in Oregon, with an economy that fluctuated dramatically with the rise and fall of lumber prices.

Far removed from Oregon’s coastal region, mineral discoveries in the interior districts and a rush of miners to the Snake River and Clearwater country in the early 1860s enhanced Portland’s position as a major transportation hub. The increased movement of Columbia River traffic boosted The Dalles as a trading center and led to the establishment of several small towns adjacent to the mines, including Baker City and John Day. This spurt of human activity served as the opening for systemic environmental change, especially to mineral-bearing streams, where entire hillsides were sluiced away, riparian habitat degraded, and salmon breeding grounds silted over.

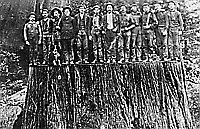

As mining developed into an industrial activity, including the construction of underground tunnels, loggers began the first large-scale cutting of inland forests to meet the demand for timber trusses and boards for ditches. To take advantage of the sudden increase in traffic on the Columbia River, a group of Portland entrepreneurs formed the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (OSNC), an enterprise that soon gained a monopoly on river transportation by controlling river portages, dominating passenger and freight traffic, and moving miners and supplies upriver and mineral wealth downriver. During the peak of prospecting in the mid 1860s, as many as seventy-five thousand miners were working interior streams.

In the Willamette Valley, farmers took advantage of the mild and wet environment to cultivate wheat and other grains, and the valley became a major producer of foodstuffs marketed outside the region. To meet the increasing demand, farmers purchased mowing machines, threshers, plows, seed drills, and reapers to speed production. The expanding acreage planted to wheat along the Willamette marked the final push toward commercial agriculture and the continued introduction of new implements. Valley producers also began taking advantage of the latest advice in modern farming techniques, forming agricultural societies, and supporting a weekly newspaper, the Willamette Farmer.

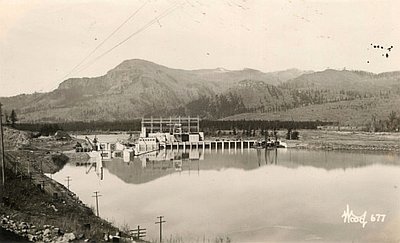

To speed the transport of goods, especially wheat, to Portland warehouses, farmers pooled their resources to remove snags and deepen some of the more troublesome bars in the Willamette River—the first effort to reshape the river into a channelized, commercial corridor. Although the completion of the Oregon and California Railroad through the valley in the early 1870s provided a faster and more efficient means of transportation up the valley, the Willamette continued to be an important traffic way well into the twentieth century.

Oregon’s population increased from 52,465 in 1860 to 90,923 in 1870, the beginning of the railroad era. Most people in western Oregon lived in the Willamette Valley counties that had the greatest agricultural output. Lane and Linn Counties, two of the more populated counties according to the 1870 census, ranked first and second in “improved land”; and Linn County ranked first in wheat production.

The importance of wheat to the valley economy was apparent to everyone and a cause for concern to some. Valley farmers produced 200,000 bushels in 1850, 660,081 bushels in 1860, and more than 2 million bushels in 1870. As railroad workers were laying the first rails south of Portland in the autumn of 1869, the Oregonian cautioned farmers against relying too heavily on wheat and urged them to find alternative crops. The newspaper advised business investors to diversify the state's economy so that it could produce more “of the other necessities of life.”

Oregon’s expanding commercial enterprises were tied to distant markets well before railroad connections linked the western valleys with Portland early in the 1870s. Following the fur-trade era, the California market, centered in San Francisco, was the first to shape and direct Oregon’s emerging resource-based economy. Newspapers constantly reminded farmers that they must produce goods that would find a convenient and paying market.

In the late 1860s, when there were hints that Pacific coastal wheat markets were becoming saturated, Portland shippers sent a cargo of wheat directly to Liverpool, England. The effort was important to the state’s “agricultural and commercial progress,” the Oregonian concluded, and was an attempt to “secure constant and remunerative markets for our products.” Portland merchants had already sent consignments of flour to New York City in another effort to establish new outlets for valley wheat farmers.

Railroad construction, beginning in the 1860s with portage lines that bypassed the rapids and falls on the mid Columbia River, vastly expanded the geographic ties between resources and markets. Railroads constructed after 1870—from Portland to the California state line, eastward along the Columbia River corridor, across the Blue Mountains, and along the Snake River into Idaho—served as “engines of empire,” according to historian Carlos Schwantes. They were symbols of industrial capitalism and required enormous financial resources, some of it originating in international banking centers in New York, London, Paris, and Berlin.

The completion of the nation’s first continental railroad in 1869, the Central Pacific and Union Pacific line, preceded construction of the Oregon and California Railroad (O&C) by only a year. The O&C was rooted in corruption, with transportation tycoon Benjamin Holladay purchasing votes to ensure that the Oregon legislature would award his company a large land grant from Congress.

Holladay completed the O&C from Portland south to Roseburg before the fallout from the panic of 1873 halted construction. Because he had vastly overextended his financial reach, he was forced into bankruptcy and ultimately lost control of the O&C to Henry Villard, who represented German bondholders. Envisioning a railroad empire in the Pacific Northwest, Villard went on to orchestrate buy-outs of the OSNC and the Northern Pacific Railroad and made Portland the terminus of the new line. With arrival of the transcontinental railroad to Portland in 1883, Oregon products could now be exported to the East Coast, people could travel more easily, and products could more efficiently be transported to the city.

Although the O&C line did not reach Sacramento until 1887, it was an enormous success in expediting the shipment of people, grains and other agricultural commodities, and incoming manufactured goods and supplies. It was especially effective in speeding farm products to Portland’s waterfront warehouses. The new line also attracted immigrants to the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue valleys; boosted agricultural production; and underscored the importance of Portland as a regional commercial center. During the O&C’s first decade of operation, the number of people in the Willamette Valley increased by 62 percent and wheat production more than doubled.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.