Reservations in Oregon came under attack after World War II. In a sharp reversal of policies established under Indian Commissioner John Collier during the 1930s, the federal government made aggressive efforts to “get out of the Indian business” early in the 1950s—that is, to terminate the relationship between tribes and the federal government.

The idea of termination gathered momentum after 1945 and became formal policy with the passage of House Concurrent Resolution 108 in 1953, which directed the federal government to terminate its special responsibility for Indians “at the earliest possible time.” The resolution further directed the “Secretary of the Interior to submit legislation putting into effect a policy of termination for certain named tribes.” The language of the termination proposals included “liberating the Indian,” “turning the Indian loose,” “emancipating the Indian,” and “terminating the trusteeship restrictions”— words suggesting that reservations were segregated ghettos.

Termination legislation was designed to remove federal supervision over trust property. Whereas Collier’s policies had strengthened tribes as social and legal entities, the new policy initiatives of President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration were directed to end Indians’ status as wards of the United States and to assimilate the tribes into the larger society.

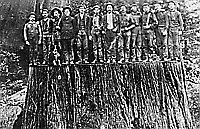

Eisenhower’s secretary of the interior was former Oregon governor Douglas McKay, who spoke for powerful timber and water resource developers in the West. There is evidence that McKay wanted his home state to serve as a showcase for the new direction in Indian policy. The effort to terminate the Klamath and other Oregon tribes, as historian Donald L. Fixico argues, “implied the ultimate destruction of tribal cultures and native life-styles, as withdrawal of federal services was intended to desegregate Indian communities and to integrate Indians with the rest of society[MY1] .” In the Klamath situation, other forces were involved—the actions of a coercive federal government eager to force termination and the attractions of the extensive ponderosa-pine stands on the reservation.

Congress passed the Klamath Termination Act in 1954, a measure authorizing the sale of reservation lands and establishing procedures for terminating the federal government’s relationship with Klamath Tribes. Enrolled tribal members then chose whether they wanted cash payments for their share of the land or if they wanted to retain their shares in the former reservation and participate in a management plan. About 22 percent of the enrolled members chose to have their shares managed by the U.S. National Bank of Oregon, which would act as trustee for the remaining tribal members. In 1961, 78 percent of the tribe received lump-sum cash payments of $43,000.

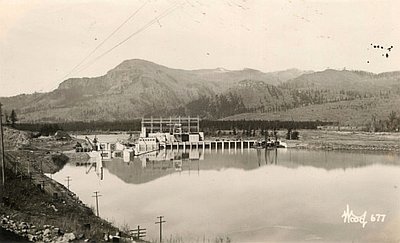

When the U.S. National Bank decided to discontinue its trust relationship in 1973, the remaining reservation land was sold and shareholders received lump-sum payments. After lengthy congressional testimony, Congress passed a bill that turned 700,000 acres of the Klamath forest into the Winema National Forest. In addition to the Klamath, the termination legislation applied to all Oregon tribes west of the Cascade Mountains.

Termination was an abysmal failure. Many Klamath people were ill prepared to manage their windfall payments, and Klamath County experienced some of the highest unemployment rates in the state. Alcoholism increased, welfare rolls expanded, health conditions spiraled downward, Indians died at a young age, and few Klamaths had access to educational opportunities. In a report on terminated tribes to the American Indian Policy Review Commission in 1976, a survey of the Klamath noted that few people owned land or were otherwise economically independent: “In general the Klamaths lost their land and have nothing to show for that loss.”

In 1973, a reversal in termination policy began with the federal recognition of Wisconsin’s terminated Menominee Tribe. In the following years, after many hearings before Congress, lawmakers granted federal recognition to the Klamath, Siletz, Grand Ronde, Cow Creek, Coquile, and Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw tribes in Oregon.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.