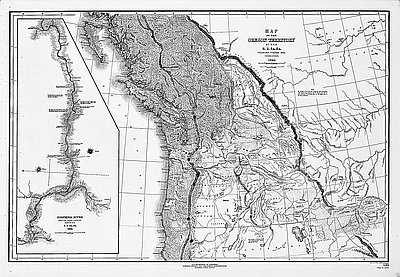

Until the end of the eighteenth century, the Columbia River country had existed in relative isolation from disease such as smallpox, measles, whooping cough, typhoid, malaria, and cholera, which had proved so deadly to people who lacked immunities to Old World contagions. While the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Ocean discouraged travel and limited access to the region for some time, that isolation began to erode in the late eighteenth century as Russian, Spanish, British, and American ships increasingly touched shore on the Northwest Coast. The best documented of the major epidemics—and a major cause of Native population decline—was a series of seasonally recurring malaria outbreaks on the lower Columbia River between 1830 and 1833. Coming first from West Africa to Central America, the initial outbreak in the Oregon Country took place near Fort Vancouver in August 1830. Spread by an insect vector—in this case, mosquitoes—malaria returned annually to ravage Indian and white populations alike, but the malarial infections affected the two peoples in dramatically different ways. While whites suffered fever and sickness, malaria was lethal to Native people.

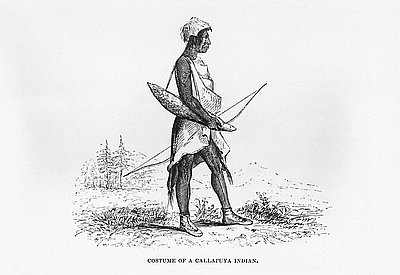

The reoccurring malaria epidemics were devastating to Indians along the lower Columbia River, in the Willamette Valley, and in villages on Oregon’s coastal estuaries. In a letter to HBC officials in October 1830, John McLoughlin estimated the Native death toll at 75 percent in the vicinity of Fort Vancouver. Botanist David Douglas recorded a similar description that same month: “A dreadfully fatal intermittent fever broke out in the lower parts of this river about eleven weeks ago, which has depopulated the country.” By the time the epidemic had run its course, about 90 percent of the fourteen thousand people who lived on the lower Columbia and in the Willamette Valley had died. When Lt. Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition visited the region in 1841, he counted 575 Chinook survivors on the Columbia and 600 Kalapuyans in the Willamette Valley.

The malaria epidemic was only one of several exogenous diseases that struck down Native people. The increasing traffic on the Oregon Trail brought new contagions, especially those associated with childhood, such as chicken pox, measles, and whooping cough. These pathogens struck disproportionately against Native children, skewing the average age of Indian communities. By the close of the American Civil War, disease had reduced the Native population on the Northwest Coast by more than 80 percent, a loss of 150,000 people, a catastrophic decrease that parallels similar declines elsewhere in the Americas. The pathogens also weakened the abilities of Indian groups to resist the increasing numbers of Euro-Americans who were entering the lower Columbia and Willamette valleys in the 1830s and 1840s.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.