Wartime conditions severely disrupted rural communities, creating dire labor shortages in agricultural and natural resource industries like logging and lumbering. Thousands of Oregonians left farms, ranches, and logging towns for centers of military production, such as Portland’s Kaiser shipyards and defense plants in Seattle and San Francisco. Although many defense workers were from outside the Northwest, residents of the region made up the largest percentage of the wartime labor force. The exodus of people from the countryside caused many of Oregon’s rural communities to decline in population during the war.

The most visible signs of change in the Pacific Northwest involved the two principal centers of war manufacturing. In the Seattle-Tacoma area, the Boeing Company employed 50,000 people in 1944, its peak production year. Three big Kaiser shipyards operated to the south in Portland and Vancouver, Washington: the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation on the Willamette River near the St. John’s Bridge; a shipyard upriver at Swan Island; and one near the Columbia River Bridge in Vancouver. The huge, federally subsidized operations employed as many as 120,000 workers at peak production, with another 40,000 people in related jobs.

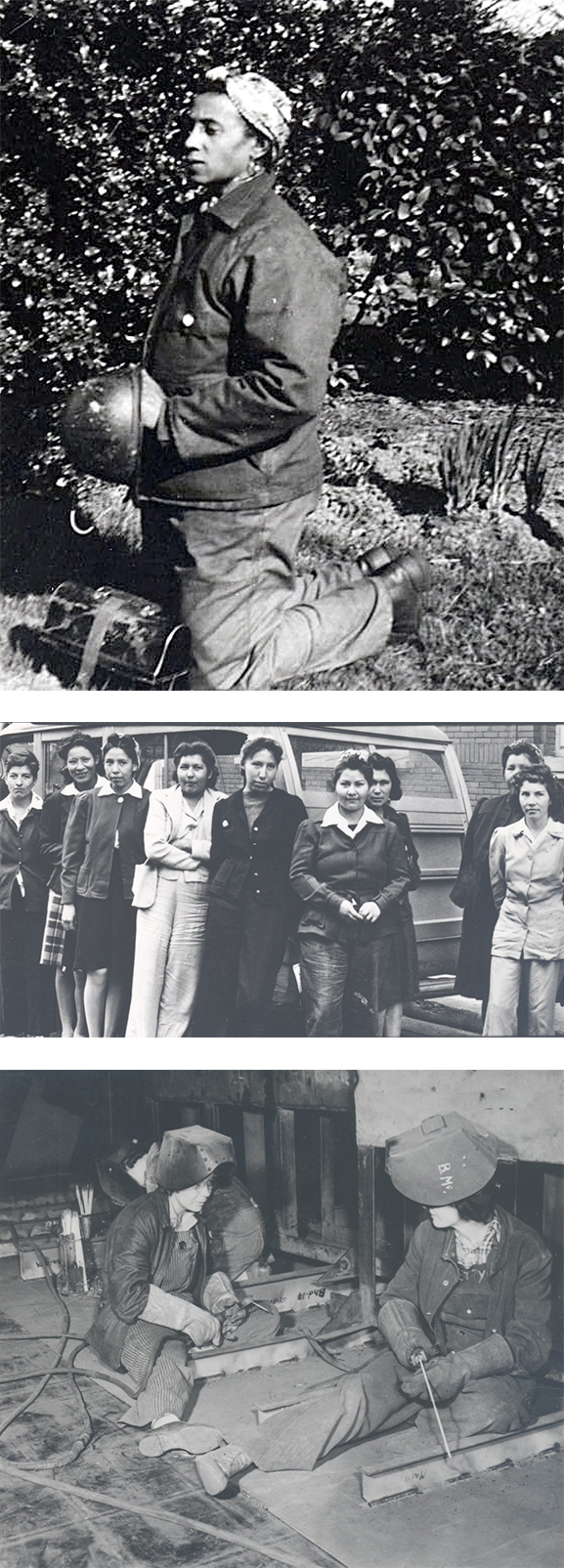

Portland residents greeted the new people moving into the city during the early 1940s with open skepticism. When the shipyards and other local defense industries began to bring in Black workers in 1943, the newcomers encountered a wall of racism and discrimination in housing, public transportation, union membership, and access to recreational facilities. There were openly offensive eating establishments, including the Coon-Chicken Inn on Northeast Sandy Boulevard. Early in the war, a former Portland city commissioner urged local officials to discourage the shipyards from recruiting minority workers, and Mayor Earl Riley worried that the incoming groups would threaten the city’s “regular way of life.”

The 1940 census listed fewer than 2,000 African Americans in a total population of 340,000 people in the Portland area. Although only a small number of Blacks had arrived in the city by September 1942, the Oregonian ran a front-page article under the headline “New Negro Migrants Worry City.” “By any measure,” historian Rudy Pearson writes, “Portland responded with prejudice and insensitivity to the wartime immigration of African Americans.”

The first influx of African American families moved into cramped quarters in the Guild’s Lake district. Because of the extreme housing shortage, newly arrived Black workers found temporary shelter with members of the established African American community, in local churches, at the Black Elks Lodge, and in Black-owned businesses.

To alleviate the housing crisis for shipyard workers, industrialist and ship-building magnate Henry J. Kaiser used federal loans to purchase 650 acres of land outside the city limits on the Oregon shore of the Columbia River. Kaiser’s company constructed housing on the floodplain for 40,000 residents, making Vanport City the state’s second largest city. With buildings supported by wooden blocks and with fiberboard walls, Vanport was the nation's largest wartime housing project.

Vanport was home to a mix of people, including a sizable number of African Americans who had made the move west to work in the shipyards. By war’s end, African Americans made up 35 percent of Vanport’s population, a much larger percentage than anywhere else in the state. A devastating flood on the Columbia River on Memorial Day in 1948, breached a railroad dike, and pounded Vanport to kindling. The destruction left 18,000 people without homes, 25 percent of them African Americans.

While the completion of Vanport in 1943 and the settlement of Blacks in inner northeast Portland’s Albina district e relieved the housing crunch, it did nothing to lessen the discriminatory practices of Portland Housing Authority officials or the racially restrictive real-estate covenants that had been put in place. Of the more than ten thousand African Americans who remained in the Portland metropolitan area at the end of the war, five thousand lived in Vanport. Pearson argues that Vanport’s destruction in the 1948 flood marked a turning point in Portland’s race relations. By the time homeless African Americans found housing in the city proper, Portland’s Black population had doubled.

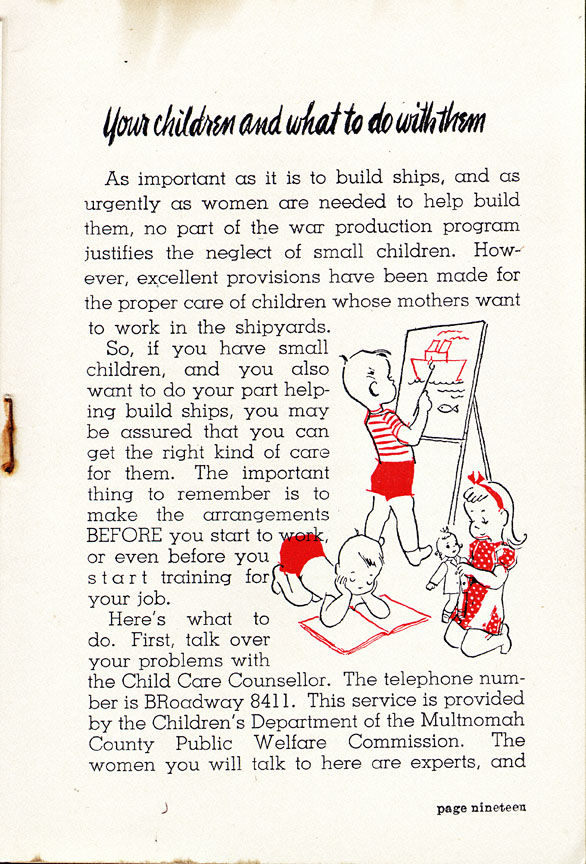

Many women also found their lives changed by the war, which transformed the nation’s workforce. Thousands of women took wage-earning jobs for the first time, a national increase of 57 percent between 1941 and 1945. At the peak of the Boeing Company’s wartime production effort south of Seattle, 46 percent of its 50,000 employees were women. At the large Portland’s Kaiser shipyards in 1944, 28,000 women comprised 30 percent of the workforce, with countless others working in smaller yards along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. To accommodate families with children, day-care centers became an important part of urban life for the first time.

The Kaiser shipyards made an early commitment to hire women to fill construction positions at its Portland and Vancouver facilities. When the Oregon Shipbuilding Company hired two women welders in April 1942, it was the first time a U.S. Maritime Commission yard employed female workers to carry out production functions. As news circulated about the shipyard’s willingness to hire women, welding schools began training more women for the work. By early 1943, all of the major shipyards operated trainee welding programs in an effort to meet the labor shortage. Sociologist Karen Skold points out that the yards hired women at an earlier time and in greater numbers than elsewhere in the nation, a reflection of the region’s dire labor shortage. Women shipyard employees earned good wages and received equal pay with men for the same kind of work.

Both Kaiser shipyard and federal officials recognized the importance of government-funded child-care accommodations for women workers, and community-based facilities were located in Portland, Vanport, and Vancouver. Two Kaiser child-care centers, strategically located at shipyard entrances, operated during all three work shifts. Staffed by professionally trained child-development experts and providing nutritionally balanced meals, the innovative centers became national showcases. At their peak, the two Portland shipyards—Oregon Shipbuilding and Swan Island—employed 16,000 women, and the two child-care centers cared for 700 children.

Hiring women for shipyard work was an uneven process. Females were overrepresented as welders and unskilled “help” jobs, but they made little headway at getting jobs where there was a sufficient supply of male workers. While hiring women to work in the shipyards challenged conventional notions about appropriate work for women, it is significant that female employees were the first to be handed “quit-slips” when the war began to wind down. “Women were temporary substitutes for men in a labor shortage,” Skold observes. Although a few women in unskilled positions held onto their jobs after the war, the Oregon Shipyard Corporation laid off its last three women welders in October 1945.

Similar working conditions prevailed at the Evans Products plant on Coos Bay, which manufactured battery separators. At Evans, 800 of the 1,200 employees were women in 1943. Because manufacturing battery separators “wasn’t that glamorous,” Dorotha Richardson later recalled, women quit for higher paying jobs in Portland or San Francisco. She also remembered that the local union forced the company to pay the same wages to men and women doing the same job.

With the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Evans laid off much of its workforce, in part because plastic was replacing wood as the principal material used in making battery separators. Although the union negotiated token employment for women in its plywood plant, only twenty women were working in the plywood division when the company began to phase out its Coos Bay operations in 1959.

Oregon’s labor shortage in natural resource industries during World War II accelerated the change to mechanized processes. Gasoline- and diesel-powered tractors replaced horses, mules, and oxen on farms and ranches. Even greater manpower deficiencies in wood operations speeded the mechanization of timber harvesting, as logging bosses began placing a premium on labor-saving devices such as the chainsaw. In the Coast and Cascade Ranges, logging operations began replacing steam-powered donkey engines with gasoline- and diesel-powered yarding machines yard and load logs. AS a result, fewer workers were needed for each operation. By the end of the war, steam power was used primarily by gyppo logging operations, small outfits that functioned with little capital and outdated, surplus equipment.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.