The Veterans Lottery and the CCC

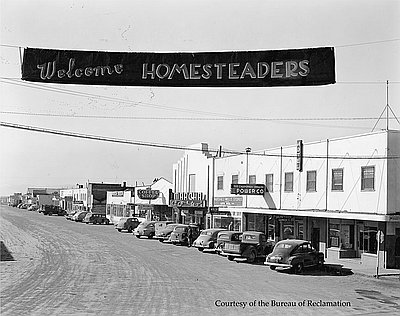

After World War II ended, the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) made eighty-six Klamath Project farm units of 160 acres or less available for homesteading. To be eligible for the lottery, one had to have prior farming experience, a record of service during the war, some cash, good health, and a good character. More than 2,000 veterans applied.

On December 18, 1946, the Klamath Union High School band played patriotic songs at the Klamath Falls armory as the drawing took place. Capsules containing contestants’ names were picked from a pickle jar and smashed open with a mallet. The lucky winners’ names were read before an anxious crowd and on nationwide radio.

One winner was Eleanor Bolesta. During the war, Bolesta, who grew up on a farm, had served the Navy in a special women’s branch, the WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). She did not like her postwar job as a secretary for the Civil Aeronautics Administration in Everett, Washington. Her husband, Chuck, who had been wounded as a Marine in Guam, wanted a drier climate for his recovery. Bolesta’s boss had been stationed at the Naval Air Station in Klamath Falls (now Kingsley Field) during the war. He suggested she apply for the lottery.

Hearing on the radio that Eleanor had won, the Bolestas drove to Klamath Falls where a BOR board interviewed them. Eleanor was asked, “How can you prove that you are head of the family?” Her answer, that she was supporting her wounded husband, satisfied the panel, and Bolesta became the first woman to win a BOR homestead.

The BOR gave the homesteaders barracks from the Japanese American concentration camp as housing materials to move to their new land. The Bolestas broke a fifty-foot half-section of the barracks plus half of a mess hall into pieces for their living quarters, in the meantime living at the internment camp.

The new homesteaders formed a potluck social club, and they received support from the surrounding community. Loans were easy to obtain and established farmers readily gave advice. The first crop the Bolestas planted on their 112-acre farm was malting barley. That same year Eleanor gave birth to Peggy, their first child.

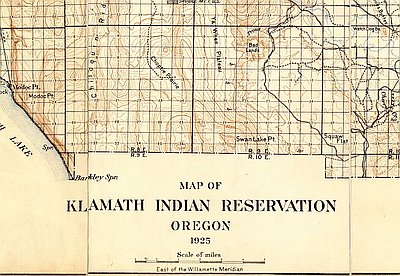

In Oregon and throughout the U.S., the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided much-needed jobs during the depths of the Great Depression. Within the Upper Basin there was a CCC project at Crater Lake, building the infrastructure of the national park there; an Indian CCC on the Klamath Reservation, making trails and doing forest maintenance; two Fish and Wildlife camps at the Tule Lake and Clear Lake wildlife refuges; and two Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) camps on Klamath Project lands.

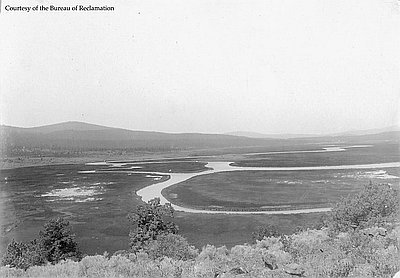

CCC Camp BR-41 was quartered two miles north of Merrill, Oregon. Everyday projects included building water control structures of timber and concrete, digging ditches, clearing weeds, and killing rodents. The excavation of J Canal required jack hammers and dynamite; to line the canal workers poured hundreds of cubic yards of concrete. There was emergency work as well. CCC crews fought forest fires like one that scorched Stukel Mountain north of Klamath Falls. When a dike broke and flooded the Tule Lake sump, one crew rapidly repaired the dike; other men, hauling grain from the fields, saved the harvest.

The daily routine was inspired by the military. Men rose at 6:00A.M., ate at 6:30, and policed their barracks and camp before starting work at 8:00. At 4:00P.M., a retreat ceremony signaled the close of the work day.

On-the-job training in such tasks as road construction and laying pipelines was available. Mr. I.L. Williamson, who conducted a vocational training conference at BR-41, explained to the camp’s technical personnel how to teach their skills. Presentation, he said, means that an instructor has to “Tell ’em, Show ’em, Ask ’em, Let ’em talk.” Application means, “Let ’em try it.”

All of the men took a course in first aid. Twice a week enrollees from the two BOR camps attended night school in Tulelake, taking classes in reading, writing, spelling, landscape gardening, auto mechanics, history, geography, photography, and journalism. The CCC educational advisor found “a surprising high percentage of enrollees at both camps were illiterate.”

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Tulelake, California

In 1917, the U.S. Reclamation Service (renamed the Bureau of Reclamation in 1923) offered 3,000 acres of land for homesteading in the Klamath Reclamation Project near Tulelake, California, …

CCC Fights Fire in Willamette National Forest

This photograph shows men digging a trench near a fire in the Willamette National Forest in about 1934. The men worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a …

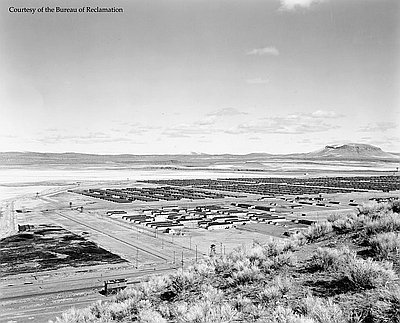

The Tule Lake Relocation Center

The Tule Lake Relocation Center, seen here in 1947, is located about thirty miles southeast of Klamath Falls near Newell and Tulelake, California. Opened on May 27, 1942, it …