The Land

A land of mountains, forests, wetlands, lakes, and rivers, the 16,400-square-mile Klamath Basin is larger than nine of the fifty states. Through the Upper Basin, which spans the Oregon/California border, flies North America’s largest population of migratory wildfowl. Straddling the border to the west, in the Siskiyou range, one finds the most biodiverse temperate mountain region on the planet. The Klamath River, which flows through this country to the California coast, ranks third in the nation as a source of wild salmon. After the Columbia, the Sacramento, and the Colorado, the Klamath is fourth in volume among the rivers of the West.

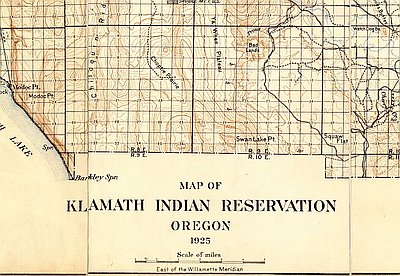

During the last century and a half, from the headwaters to the estuary, the Klamath Basin has witnessed a succession of wars and resource conflicts over land, minerals, trees, fish, and water. These events include the Modoc War, which was fought with rifles within a formidable lava bed landscape in the 1870s; the termination of the richly forested Klamath Indian Reservation in the 1950s; and the national controversy concerning water allocations and endangered species that erupted in 2001.

Yet even when local events hit the headlines, the Klamath Basin itself remains little known. Roadmaps and state maps do not distinguish this region, which is defined by mountains and water rather than by routes and borders.

The Klamath Basin is a mystery even to those who live here. The river whose drainage defines this territory is not navigable; no road runs along major portions of its 254 miles; and those who own the country that it and its tributaries flow through—tribes, federal agencies, forestry corporations, family farmers and ranchers, townspeople, back-to-the-land communities—exist within separate jurisdictions, economic systems, and mindsets. They are often at odds, unable to understand each other.

A history of the region emphasizing the interplay between the environment and human life can dispel some of the mystery.

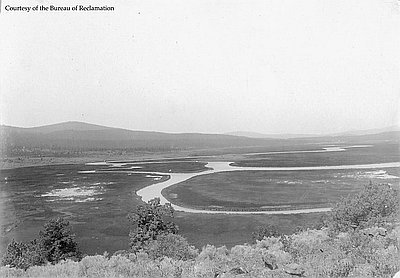

Close by the expanse of high desert country known as the Great Basin, the waters within the Upper Basin of the Klamath drainage create an amazing oasis. The Sycan and Williamson rivers flow through vast marshlands into the largest body of freshwater in the American West. From the southern shore of Upper Klamath Lake, one of the nation’s shortest rivers, the Link, fills Lake Ewauna. From there, streams the Klamath, fourth in volume among U.S. rivers that make their way to the Pacific.

About 11,000 years ago when people first came to the Upper Basin, water covered much of the area that is land today. Over millennia reeds and grasses that grew within large shallow lakes rotted and built up, forming peat-rich soils. Ancient lakes turned into marshlands.

Today, Sycan Marsh and Klamath Marsh and other wetlands of the region serve as giant sponges. They hold the waters that seep down mountain slopes. When swollen rivers overflow their channels, they absorb the spill-over. They nourish the great forests of ponderosa pine that spread out across the land, and they support wildlife including the great flocks of migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway.

Mid-nineteenth century pioneers who traveled across the Great Basin along the Applegate Trail to the Upper Basin looked across Goose Lake, Tule Lake, and Lower Klamath Lake and marveled. If this land posed a problem in their eyes, it was that it had too much water, too little solid ground. In the late nineteenth century, when farmers and ranchers began to drain marshes and shrink lakes to make room for cattle and crops, who could have imagined that the time would ever come when the Klamath’s Upper Basin did not have enough water for all?

The Klamath Basin is a ten-and-a-half-million-acre region known for the extraordinary beauty of its lakes and mountains, the wealth of its waters, its great forests, and its profusion of animal and birdlife. More than one million birds, including 1,000 wintering bald eagles, rest here during their annual journey along the Pacific Flyway. The Klamath River, which channels water from the Upper Basin before plunging westward through mountains to the sea, is the third greatest producer of Pacific salmon after the Columbia and Sacramento.

There are six national wildlife refuges and three national parks within the Klamath Basin. As author William Kittredge remarks, it “is a national treasure, like the Hudson River, the Mississippi, or the Everglade. Much of it belongs to citizens everywhere.”

The river’s headwaters flow from Upper Klamath Lake, the largest body of fresh water west of the Rockies. Almost thirty miles long and eight miles wide, the lake ranges in depth from eight to sixty feet. Before the federal Bureau of Reclamation’s Klamath Project drained much of the Upper Basin to clear land for ranching and agriculture, the upper lake was one of a chain of large lakes, including Agency Lake to the north and Lower Klamath Lake, Tule Lake, and Clear Lake to the south. When trapper Peter Skene Ogden first came here in 1826 he observed “the Country as far as the eye can reach being one continued Swamp and Lakes.”

Mountains define the Upper Basin. To the northwest rises Mount Thielsen, beside the upper lake rests Mount McLoughlin, and at the south central edge of the river’s drainage, the majestic Mount Shasta, all snow-capped volcanic peaks within the Cascade Range. The mountains west of Shasta are younger than the Klamath River, which cut its course through them as they rose.

The climate of those western mountains is wet, like much of the Pacific Northwest. The Upper Basin, in contrast, is dry and sunny much of the year; the mountains to its west block moisture coming from the Pacific.

Ranging from Canada to Arizona, the ponderosa is the most widespread pine in North America. The dry, high-altitude climate of the Upper Klamath Basin offers this tree an ideal habitat, and the Indian practice of burning forests, which continued for thousands of years, helped the ponderosa thrive. It has thick bark, and its seeds survive intense heat. Fires stimulate the growth of some plants while clearing out underbrush, making bears, elk, and other large animals better able to move through the forests, an advantage for hunters.

One of the largest ponderosa forests anywhere grows east of the Cascades, between Bend and Klamath Falls. Named for its ponderous height, which reaches above 30 meters—about 100 feet—the ponderosa is useful in many ways. Natives of the lakelands in the Upper Basin made dugout canoes prior to the Treaty of 1864, which established the Klamath Reservation. Settlers, who built homes in the Klamath Basin from the 1860s on, found that the even-grained wood makes good shelves, panels, frames, and furniture. They built mills along rivers and creeks to turn out boards.

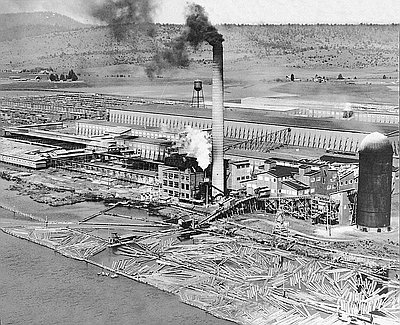

When the Southern Pacific Railroad extended its tracks to Klamath Falls in 1909, the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company built a huge mill there and became the region’s predominant property owner. In northern Klamath County, the Shevlin-Hixon company operated a huge portable logging camp with 350 workers; its mill worked two shifts a day. Timber became the state’s number one industry, with Oregon producing more lumber than any other state in the union.

The Cold War era brought a tremendous demand for building materials. As the nation’s population boomed, suburbs spread across California, just down the tracks. Yet by 1950, the diminished supply of logs could no longer support the Shevlin-Hixon mill. The company sold its facilities and equipment and laid off 850 men.

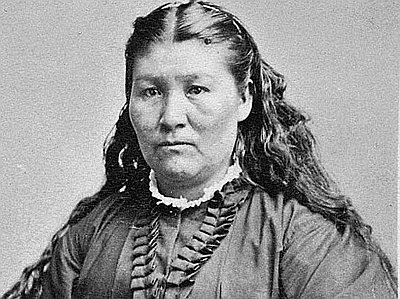

Ponderosa remained abundant within the reservation of the Klamath Tribes. The Termination Act of 1954 liquidated the reservation, and in 1961 Congress nationalized its forest, naming the Klamath lands for Winema, a Modoc Indian woman. Today half of Klamath County lies within the Frémont-Winema National Forest.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

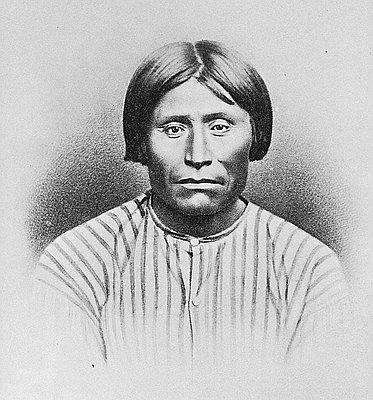

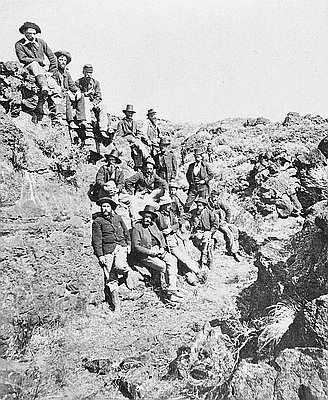

Modoc War

This photo, taken shortly after the defeat of the Modoc Indians, shows some of the officers involved in the 1872-1873 conflict between the Modocs and the U.S. Army. …

Ponderosa Pine, Prineville, 1931

Forest fires are an important component of the ecosystem. The Native population used fire as a tool to enhance the production of food, opening the dense forest to light …

Weyerhaeuser Timber Company

At the time of this photo in 1941, Weyerhaeuser Klamath Falls employed approximately 1,200 men and produced 200 million feet of wood products each year. Weyerhaeuser experienced a …