Farming the Wildlife Refuges

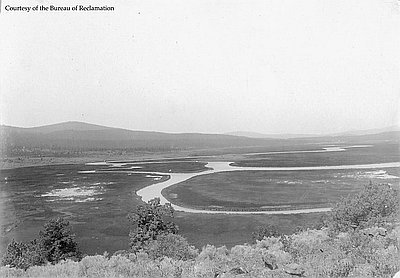

Not all of the Klamath Project lands became available for homesteading after World War II. Conservationists and hunters did not want the wildlife refuges on the project to be farmed or harmed by farmers. Henry Clineschmidt, heading the Associated Sportsmen of California, complained that irrigators were draining Lower Klamath Lake even though “fresh water is urgently needed to halt an epidemic of botulism killing thousands of ducks in the lower lake area.” Meanwhile, farmers complained that ducks and geese were consuming their crops, while hunters trampled their fields.

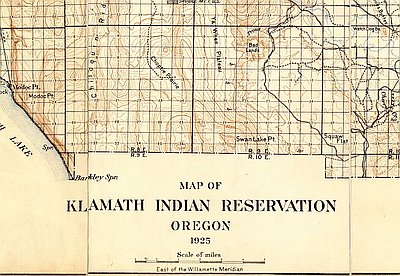

Instead of homesteading, farmers leased 22,000 acres of the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Their tractors pushed boundary-marking humps of earth, or berms, around 100-acre plots of rich soil on the lease lands. When a former governor of Oregon, Douglas McKay, became President Dwight Eisenhower’s Secretary of the Interior in 1954, Klamath Basin farmers urged him to sell these lands to private owners rather than restore the wildlife marshes.

A decade later California’s Senator Thomas Kuchel proposed and passed legislation that left both sides of the controversy dissatisfied. The Kuchel Act of 1964 required the Secretary of the Interior to administer the refuges “for the major purpose of waterfowl management, but with full consideration to optimum agricultural use that is consistent herewith.” It left unanswered the question of which agency of the Interior Department would manage the refuge, the Fish and Wildlife Service or the Bureau of Reclamation. Eventually, in 1977, Reclamation took control.

Many farmers and ranchers argue that their uses of the wildlife refuges are in the birds’ best interests. Wildfowl feast on the grains that are grown there, says veteran farmer John Staunton. Portions of these crops are left in the refuge fields for the wildlife, and in addition, the refuge grows a buffer of barley to draw wildfowl away from the farmers’ lands. Gerda Hyde, whose ranch uses hundreds of tons of hay grown within the Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge each year, maintains that the harvest stimulates the growth of plants within the marsh. “The hayed areas,” says Hyde, “produce more ducks and geese.”

A different view appears in A Conservation Vision for the Klamath Basin published by a coalition including the Wilderness Society, Water Watch, and the Klamath Basin Audubon Society. These environmental organizations want commercial agriculture within the refuges “phased out in an equitable manner” and the lands “returned to a natural habitat condition.”

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.