Birds of a Feather

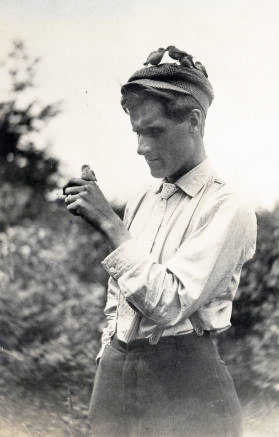

William L. Finley (right) and Herman Bohlman, Klamath Marsh, about 1905. William L. Finley (right) and Herman Bohlman, Klamath Marsh, about 1905.

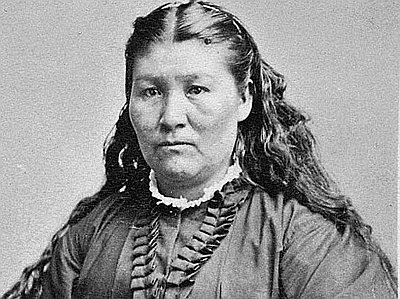

In 1902, William L. Finley of Portland organized the Oregon chapter of the Audubon Society. That same year Congress passed the Newlands Act, establishing the Reclamation Service, later renamed the Bureau of Reclamation.

During this era, fine women fancied feathered hats. The most profitable place for “plume-hunters” was Lower Klamath Lake, where the shooting of grebes, terns, and gulls produced bales of feathered birdskins for the milliners of New York City. Also popular were “game birds,” ducks and geese which hunters shot for San Francisco restaurants. According to Finley, “when the birds are flying, each hunter will bag from one hundred to one hundred fifty birds a day.”

Campaigning to protect wildfowl from unlimited market hunting, Finley photographed the birds of the Lower Klamath Marsh for national magazines. In 1907, after seeing Finley photographs, President Theodore Roosevelt created the first bird refuges in the West. The Lower Klamath Lake and the Malheur Lake National Wildlife Refuges were also the first to be placed on agriculturally valuable lands.

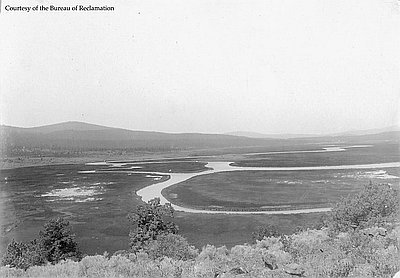

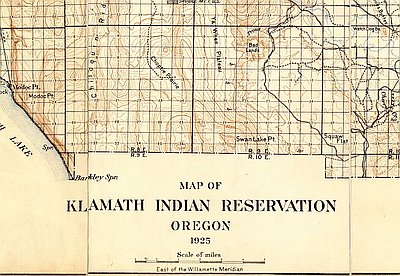

By 1915, the Klamath Water Users Association had persuaded President Wilson to reduce the Lower Klamath Lake refuge from 80,000 acres to 53,600. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Reclamation used the Southern Pacific railbed as a dike to block overflow from the Klamath River that refilled the shallow lower lake. Its waters quickly evaporated under the abundant sunlight of the Upper Basin. By 1922, a 365-acre pond was all that remained.

Nesting colonies of migratory wildfowl disappeared. Lands east of the lake became infested with grasshoppers, whose leaping population birds no longer restrained. Peat soils started to burn, raising clouds of ash that obscured the skies of Klamath Falls. On October 26, 1922, the Klamath Evening Herald proclaimed: “DUST CLOSES SCHOOLS. Storm Held Worst in History of City: Housewives Aroused!” Finley described what was once Lower Klamath Lake as “a great desert waste of dry peat and alkali.”

President Calvin Coolidge responded by establishing the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge in 1928. In the 1940s, the Bureau of Reclamation built a 6,000-foot tunnel through Sheepy Ridge and pumped runoff water from the Tule Lake Basin up sixty feet into the Lower Klamath drainage. This feat of engineering refilled the wetlands, and birds began to return. By the fall of 1955, an estimated 7 million birds visited the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges, offering innumerable wildlife images for photographers in the Finley tradition.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

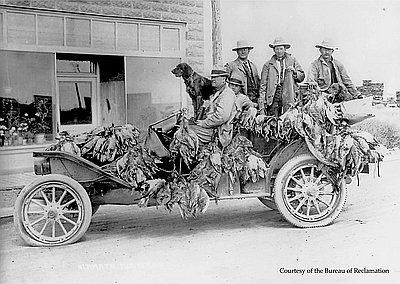

Duck Hunters

The Klamath National Wildlife Refuges, which includes the Upper Klamath, Klamath Marsh, and Bear Valley Refuges in Oregon and the Lower Klamath, Tule Lake, and Clear Lake Refuges …

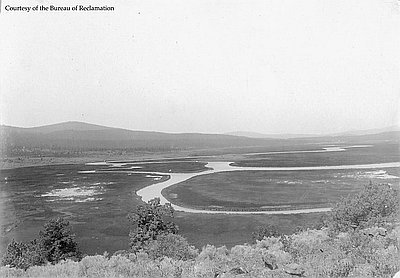

Lower Klamath Marshes

The Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge complex includes the Upper Klamath, Klamath Marsh, and Bear Valley Refuges in Oregon and the Lower Klamath, Tule Lake, and Clear Lake …