Wild Salmon

Salmon fishing on the Columbia, image by Benjamin Gifford.

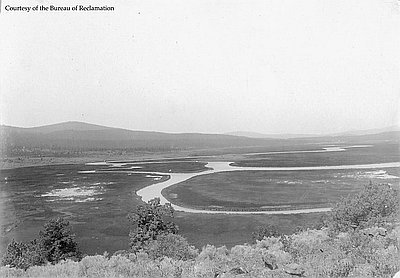

Six species of wild salmon spread out across the Pacific Northwest about the same time that human beings did, at the end of the last Ice Age. Migrating in the millions from the ocean into coastal rivers, tributaries, and upland streams, salmon offered an abundant and recurring source of food. Their bodies enriched the entire region, bringing nutrients from the sea to the continental waters and land.

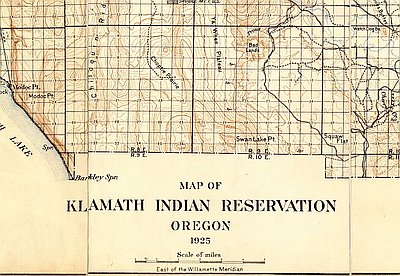

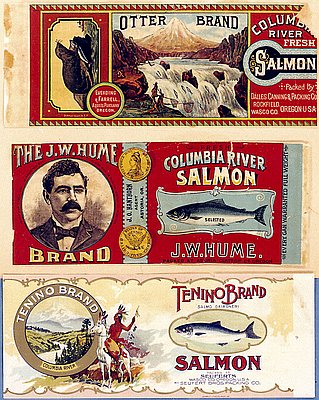

Of the six species, chum, sockeye, and pink salmon favor rivers further north; chinook, coho, and steelhead inhabit the Klamath. The first salmon of the year, the spring chinook, is the largest, tastiest, and most powerful of them all. This was the fish that the cannery industry prized until the crash of salmon populations led to the closure of canneries in the 1930s. Until dams blocked their passage, spring chinook traveled upriver the entire 254 miles of the Klamath, into the upper lake and beyond, to the Sprague, Sycan, and Williamson rivers, spawning throughout the Klamath Basin.

Today, “pen fish” produced at hatcheries below Iron Gate Dam and below Lewiston Dam on the Trinity compete with wild salmon for food and habitat within the lower branches of the river system. But these do not compensate for the reduction of wild salmon stocks. Hatchery salmon lack the genetic diversity of wild fish, which have the resilience to adapt to a wide range of conditions. The need to protect wild salmon, including Klamath River coho—listed under the Endangered Species Act as threatened by extinction—has severely restricted the off-shore commercial fishery, a once thriving multi-billion dollar industry.

Wild salmon, with their passionate upriver struggle to spawn in the waters where they were born, have inspired people for thousands of years. So fundamental have salmon been for the peoples of the Klamath River that the Yurok word for salmon, nepu, means food itself— “that which is eaten.” The Yurok creation story, like that of the Karuk upriver, speaks of a divine being who gave the people salmon for their survival. The ceremonial cycles of these river tribes center upon the coming, catching, and consumption of salmon. The First Salmon Ceremony, which the Yuroks held in the early spring at the estuary, has not occurred for a century, yet the World Renewal Ceremony, celebrated at the height of the fall chinook run, remains vital to the spiritual life of Yurok, Hupa, and Karuk tribal members.

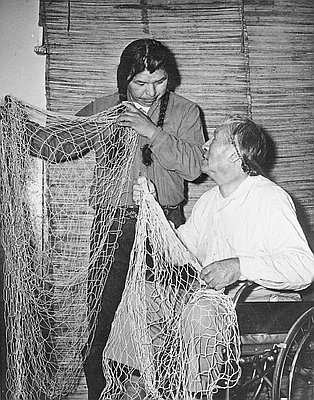

Members of the Klamath River tribes continue to subsist on salmon. They use a variety of methods to catch them. Downriver, Yuroks catch fish in gillnets. Hanging vertically within the river, gillnets have a mesh designed to let small salmon pass through while trapping large ones by the gills. Karuks use dipnets that dangle from ten-foot poles to scoop fish from pools within the river.

For those who fish, the continuing existence of salmon within the Klamath Basin is an emotional and spiritual as well as economic concern. Yet the efforts to preserve wild fish and restore their habitat are themselves an upstream struggle.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

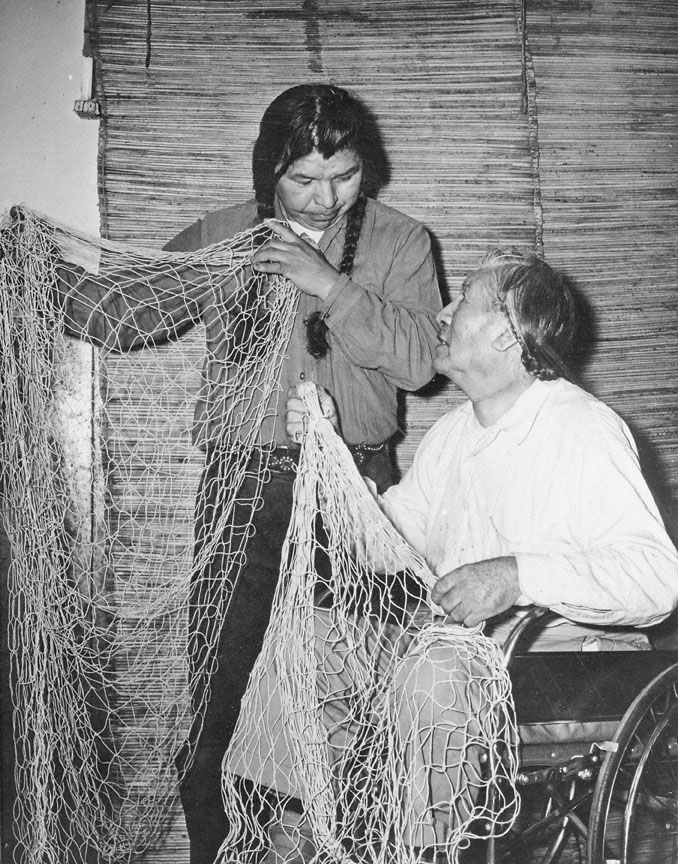

Fishing Nets

This photo shows Celilo Village residents Jimmy George, left, and Charley Quittoken, right, holding up fishing nets once used to catch salmon at Celilo Falls. Netmaking has long …

Columbia River Salmon Canning Labels

These labels show three different brands of Columbia River salmon sold during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At the top is the Otter Brand, packed by The …

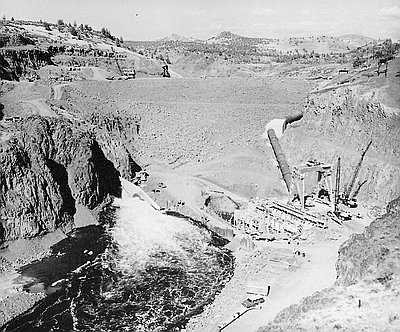

Iron Gate Dam

Iron Gate Dam, pictured here under construction in 1961, is one of seven dams on the Klamath River used by the Department of Interior’s Klamath Reclamation Project, which …