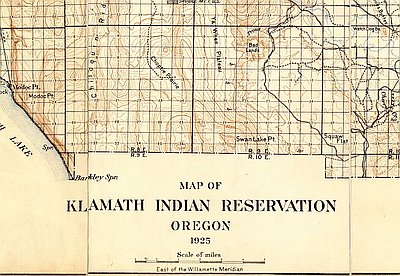

The Klamath and Modoc peoples share a reservation with the Yahooskin, a Paiute tribe from high desert country to the east. Their ancestors spoke dialects of the same language while living in different parts of the Klamath Basin. Klamath and Modoc alike called themselves maklaks, the people. The major Klamath bands were known as E’ukskni—people of the lake—who lived north of Upper Klamath Lake, and Plaikni—uplanders—whose villages were south of the Sprague River. Mo’dokni inhabited the Lost River drainage around Tule Lake and Clear Lake.

Until the twentieth century, Klamath traders traveled north from their lava-rich country to Celilo Falls on the Columbia River to exchange obsidian glass arrowheads for other goods. The Chinook Jargon, used as a trading dialect by the tribes that met there, gave the Clamitte their contemporary name.

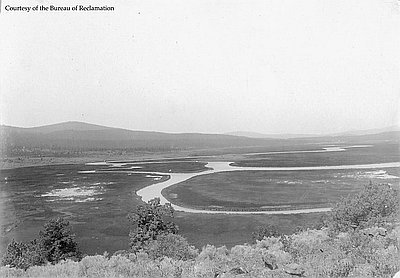

Within the Klamath Basin, tribal members used canoes for transportation along rivers, through marshes and across lakes. From canoes they fished using two-pronged spears, harvested wocus—a pond lily seed that they ground into flour—hunted waterfowl, collected duck eggs, and gathered tule reeds.

Tules growing in the lakes and marshes gave the maklaks a versatile material. They made canoes of tules, built homes with tules arranged on a framework of poles, covered communal storage pits with tule mats, wore tule leggings and tule sandals, and wove tules into baskets to sift wocus through. Shells of dried wocus seeds yielded a dye for tules used in basket-making.

Great quantities of wocus were stored in those mat-covered pits. Ten thousand acres of the lily grew in Klamath Marsh alone, providing a food so abundant that maklaks depended on it to survive when other foods were not available. Also helping the maklaks to survive harsh winters at 4,000 feet, with fierce winds and heavy snows, was the faith that their creator had provided them everything they needed.

With no order from General E.R.S. Canby, who commanded the Army’s Department of the Pacific, or from Colonel Wheaten, who headed Oregon’s District of the Lakes, Major Green sent troops from Fort Klamath to Lost River to bring Captain Jack’s band of Modocs back to the Klamath Reservation. The major made this dangerous move after a visit from the reservation sub-agent, Ivan Applegate. Applegate reported that settlers, desperate to get rid of the hundred or so Modoc “desperadoes,” might attack Jack’s camp on their own.

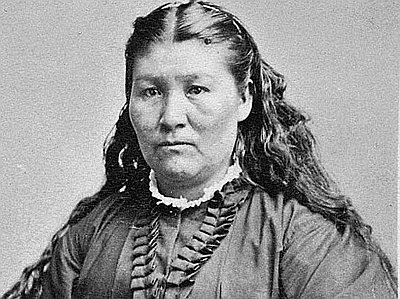

When the Army entered the Modoc camp at daybreak, November 29, 1872, an attempt to disarm the Indians sparked an exchange of gunshots. At that moment, settlers came out of hiding and attacked Hooker Jim’s village across the river. Several children, two men, and at least one woman died under fire. The rest of the Modocs fled; their destination: a natural lava bed fortress south of Tule Lake. On the way, Hooker Jim and his men killed several settlers, including Henry Miller, who had befriended Modocs. Suddenly, war was inevitable.

Against the Modoc band, the Army assembled a force of 330 men. Foggy weather and the rugged terrain, however, frustrated the first federal troops. The first assault on January 17, 1872, became a rout, with Modocs shooting at will. That battle left thirty-seven soldiers and civilian volunteers dead or wounded. Not a single Modoc was harmed.

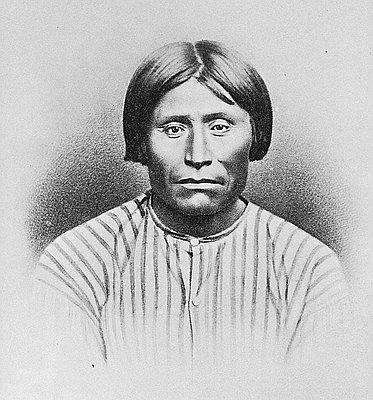

Knowing that the Army could not dislodge the Indians from their stronghold without great cost in lives, General Canby attempted to negotiate an end to the war. Canby favored a Modoc reservation on Lost River but was not authorized to offer one. While talks continued, the general brought more troops into the vicinity of the Indian stronghold. Failing to get the general to agree even to let Modocs stay in the lava beds, Captain Jack yielded to pressure from Hooker Jim and other men who had murdered settlers. They feared being hanged as part of a peace agreement and insisted that Canby be assassinated during a negotiation session. On Good Friday, April 11, 1873, the Modoc leader shot General Canby dead. His men killed another peace commissioner, Reverend Eleasar Thomas, and wounded a third, Alfred B. Meacham.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.