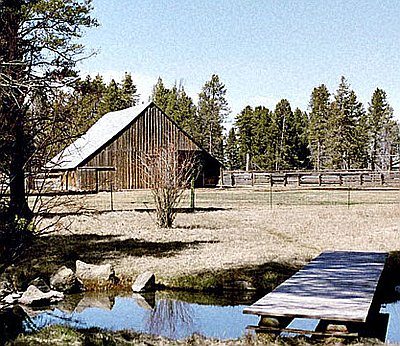

Like other ranches, Yamsi, at the headwaters of the Williamson River, doubles as a resort. What is rare about this ranch, which Dayton and Gerda Hyde have worked since 1950, is that few of its visitors are dudes on horseback; many fish for trout with rod and reel. As a result, not only the philosophy but the balance sheets of the Hydes require that as they run the ranch, they maintain excellent water quality within the Williamson.

The Hydes practice holistic methods of land management. They take into account the effects of each decision on the land, plants, water, and fish as well as on the cattle. Rather than manipulate their land to serve their stock, they raise their herds in ways that fit the land. This includes fencing off riparian areas so that hooves do not destroy shade and erode soil along riverbanks. It means keeping cattle on the move so that they graze each area once and go on, letting the newly fertilized grasslands get a rest.

Gerda Hyde, who raised her family of five children on the ranch, explains that the method of keeping cattle on the move corresponds to the way that ruminants and the grasslands co-evolved. Predators pick off animals that are sick and slow, pressuring herds to stay in bunches. One bite from moving grazers stimulates grass; repeated munching wears it down. Hyde wants “a lot of impact for a short term, and then move on.”

The only pollutants the Hydes permit on their ranch come naturally. They do not use artificial fertilizers, insecticides, or hormonal additives. Consequently, the beef raised at Yamsi qualifies to be sold through the Oregon Country Beef cooperative. This is a group of forty ranches that sells “natural beef” to whole food stores in western cities. Not only does the beef that the Oregon cooperative markets grow in healthy surroundings, according to Gerda Hyde, its taste is superior.

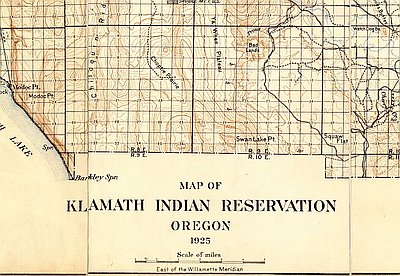

There are competing visions of the future of the Upper Basin.

Many residents want this to remain a haven for small ranches and family farms. To protect their water supply from federal restrictions, some farmers and ranchers have adopted practices that are compatible with the needs of wildlife—restoring wetlands on their own properties and fencing riparian areas, for example.

Family farmers recognize that their crops cannot compete in price with the produce of agribusiness giants or of countries that export inexpensively grown goods under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Still, the region’s alfalfa, onions, and potatoes are exceptional in quality and can find discriminating buyers.

Yet even in good years, small farms make little money. Most farm families have at least one earner working somewhere else for wages. And in spite of the appeal of the farming life, few children of Upper Basin farmers intend to stay in the region. “It looks like we’re in danger of losing a generation of farmers,” observed Dan Keppen, executive director of the Klamath Water Users Association.

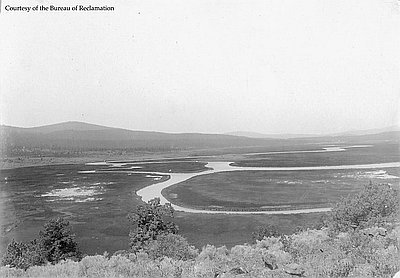

Environmental visionaries imagine an “Everglades of the West.” They advocate the end of the Klamath Project and the reversion of ranches and farmlands to the lakes and marshes of a century and a half ago. Although the decimation of wildfowl has other causes besides the draining of Klamath Basin lakes and wetlands, the flooding of fields and elimination of pesticides should increase the numbers of migratory birds. Larger lakes and marshes would also increase sucker habitat. Removing the dams along the Klamath River might bring wild salmon back to the Upper Basin.

The economic basis of this ecotopia would be the recreation industry. People would come for hunting, fishing, birdwatching, hiking, and whitewater rafting. Hotels, resorts, restaurants, and other services for tourists would prosper. Some envision a revival of the commercial fishing industry as well by increasing salmon habitat in the Upper Basin and restoring water flows through the Trinity and other tributaries downriver.

A number of citizens want to combine these visions and rebuild the economy so that small farms and ranches become compatible with environmental restoration and recreation. However, an ongoing increase in residential land use may foreclose these alternatives. As once farmed fields are paved for housing, a mix of light industry and other businesses could move into the region attracted by its low-cost land, healthy climate, and scenic beauty.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.