On the Far Fringes of Two Empires

Euro-Americans penetrated southeastern Oregon in the 1820s when British fur-trapping brigades sought to trap out the streams and discourage American exploration. In the 1840s Americans followed the trappers’ trails and began to record the region's geography on maps. The Northern Paiute struggled with the beginnings of white settlement during the 1840s and 1850s, and the resulting hostile interactions bought the U.S. Army to the High Desert. The so-called Snake Indian Wars of the 1860s ended with the Natives’ defeat and their relocation to a reservation.

Far from the ocean and with no great rivers flowing through it, southeastern Oregon remained unexplored long after the first whites had been in other parts of the Pacific Northwest. In 1805-1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their Corps of Discovery, the first Americans to explore the interior of the Pacific Northwest, followed rivers that flowed considerably to the north of the High Desert. In 1811, New York fur magnate John Jacob Astor’s men stumbled their way through a different route on their way to the Pacific, also passing well north of the Great Basin.

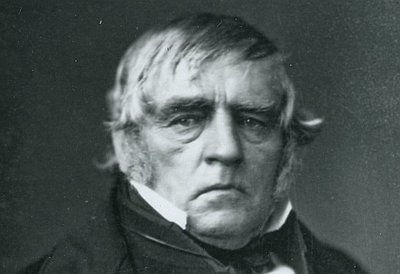

Peter Skene Ogden’s Snake Country Brigades in 1826-1827 brought the first non-Indians through the heart of southeastern Oregon. The term “Snake Country” came from neighboring Indians’ name for the Shoshone and Paiute of the Snake River Plain and the northern Great Basin. This party of Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) trappers included nearly forty French Canadian, Métis, and Iroquois men.

Ogden’s trappers—along with their Native wives, young children, a few dogs, and horses—traveled in midwinter, when the beaver pelts were prime. While their husbands trapped, the women tended the camp, fixed meals, guarded the horses, and laboriously prepared beaver pelts for travel. Chief Trader Ogden, then thirty-two years old and a seasoned hand, was under orders to trap out the Snake Country’s streams in order to create a “fur desert” barrier that would discourage American trappers from invading the company’s lucrative empire in the Northwest.

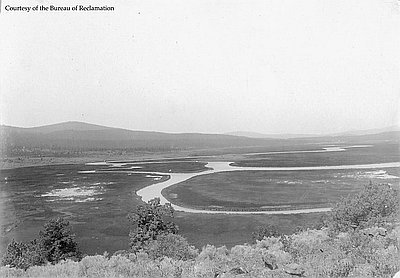

Neither Ogden, a British subject and educated gentleman, nor his trappers seemed much impressed with the Snake Country—its vast plains of “wormwood,” or sagebrush, held few beaver in its streams—or with its shy and sometimes hostile Paiute inhabitants. Ogden explored the wide expanse of Harney Valley during November 1826, before heading west across the sagebrush flats of present-day southeastern Deschutes County to the Deschutes River, and then on to the south and west out of the desert country. His brigade reentered the region near Goose Lake in the spring of 1827, passing through the Warner Valley and continuing northeastward to the Snake River. Leading the following year’s HBC expedition, Ogden traveled south through the Malheur and Owyhee River basins on his way to northern Nevada. Another HBC chief trader, John Work, led a brigade through the region in 1831 and 1832.

Relations between Native people and trappers in southeastern Oregon were often poor. Many of the earliest whites despised the Northern Paiute, Bannock, and Shoshone people, who they feared as potential thieves and marauders. The Owyhee River had earned its name in 1819, when two Hawaiian members of a fur brigade were slain by Indians. British fur traders had brought Hawaiians to the region in part because of their strength as swimmers, an important skill when negotiating Northwest rivers. In early 1826, when Ogden’s men discovered that Paiutes had stolen a large quantity of pelts cached along a river, they dubbed the stream Malheur (“Unfortunate”) River. It was probably John Work’s trappers who unknowingly carried malaria into the Harney Valley and other swampy basins in the region. Whites had brought malaria to the West Coast, and a severe “fever and ague” outbreak in the early 1830s carried off large numbers of Native people throughout the more densely settled sections of the Pacific Northwest and central California.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.