A Magnificent Country

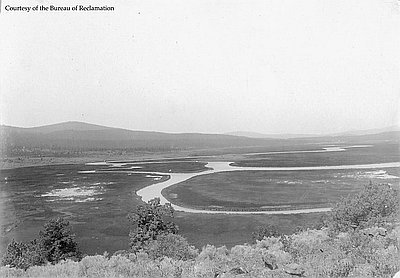

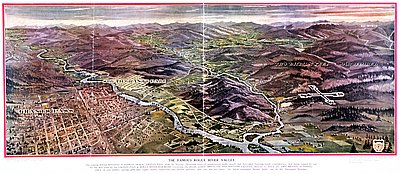

In the southeastern quadrant of Oregon—which largely coincides with the limits of Lake Harney, southeastern Deschutes, and all but the northernmost tip of Malheur County—the map shows no interstate highways and little land that is not owned by the federal government. This is an isolated region with few towns, none of them over 3,500 in population; no interstate highways; and no railroads other than one dead-end spur line that penetrates the southern fringe of the region. The map, however, does note the sand dunes, vast alkaline flats, and bone-dry ancient lakebeds that are set among an expanse of sagebrush, a landscape that hints of a dramatically different climate in the region’s past.

Included as a warning to travelers, the words Great Sandy Desert were etched across a portion of southeastern Oregon on an 1881 map. National Geographic magazine’s 1996 “Map of the United States, Physical Landscape,” features the identical phrase for the same area. For a century and a half, perceptions of southeastern Oregon have been marked by strong continuities such as these. To many twentieth-century automobile travelers, southeastern Oregon seems little more than a long day’s blur of sagebrush and junipers, breathtakingly bright clear skies, and a desolate stretch of highway.

In a real sense, southeastern Oregon is the state’s Empty Quarter. particularly in terms of its population numbers—less than 1.5 percent of the state’s total—and density—well under one person per square mile. In recent years, promoters and journalists coined more alluring names for the region: Oregon’s Outback, The Great Wide Open, Infinity of Sagebrush and Rimrock, Oregon’s Cowboy Country, and the more historically accurate Buckaroo Country.

It was not always so. With a dynamic landscape where climate change and other conditions, southeastern Oregon has supported widely fluctuating numbers of people. As recently as the 1910s and 1920s, hundreds of homesteaders’ cabins dotted the sage plains. The story of how people have adapted to the isolated High Desert—from the earliest human arrivals over 13,000 years ago to the ranchers and settlers of the last half-century is worthy of knowing, worthy of telling.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OE staff, 2014.