Dry-Farm Homesteading

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Pacific Northwest had transcontinental railroad lines of its own. As a consequence, during the opening decades of the twentieth century, much of Oregon swelled with people and hummed with what most of them praised as “progress.” Even isolated southeastern Oregon took part in the region’s boom time, as hundreds of would-be farmers flocked to the High Desert and took up homesteads. Between 1900 and 1910, the homesteading boom contributed to a 63 percent increase in Lake County’s population, with a similar trend in Harney and southeastern Deschutes Counties. They came from throughout the United States and Europe, arriving in the High Desert as part of a much wider phenomenon—the “last rush for free land” spurred by a cycle of moist weather coupled with an optimistic belief in the success of dry farming.

Between 1905 and 1920, more land in the American West was claimed under the federal homestead laws than had been claimed during the previous four decades of the Homestead Act. Most of it, like that homesteaded in southeastern the High Desert, was, to put it charitably, “marginal”—poorly watered, alkali-soiled, and higher-elevation land passed over by farmers during earlier decades. The “gospel of dryland farming,” spread by both true believers and promoters, attracted scores of midwesterners and others to southeastern Oregon between 1905 and 1914. With a period of success during these first years, due to unusually wet, mild weather, and with the high price for grain during World War I, the homesteader influx continued until 1918.

Many of the homesteaders—town and city people with little to no experience in farming—the newcomers settled quarter-section and half-section claims on the sagebrush flats, the former Ice Age lakebeds, of Fort Rock Valley, Christmas Lake Valley, Harney Valley, and Catlow Valley. Even the rocky wastes of southeastern Deschutes County drew its share of homesteaders. In addition to a one- or two-room cabin, a typical homestead might have only by a privy, a hand-dug well, perhaps a windmill, a fenced patch of summer vegetables, and a small acreage of dry-farmed rye. Long-time central Oregon journalist Phil Brogran later wrote that “at night, kerosene lights blazed in the small windows of scores of cabins…[from a distant high point] the lights looked like twinkling stars.”

The homesteaders were served by tiny and short-lived villages, as well as even smaller hamlets that had only a grade school and a post office, including Fremont, Lake, Arrow, Fleetwood, Vista, Stauffer, Sink, Buffalo, Viewpoint, Loma, Woodrow, Catlow, Berdugo, Beckley, and Blitzen. Only Millican, Hampton, Brothers, and Fort Rock survived to the present day, the first three simply because of their location as fuel stops on present-day Highway 20, and Fort Rock because of the success of large-scale well irrigation in the Fort Rock Valley.

A significant portion of southeastern Oregon’s dry-farm homesteaders—perhaps as many as one in six—were young, single women on their own. This fact was one example of a wider trend in the United Stats at the time—women’s increased self-reliance and participation in the national economy. Fort Rock rancher Reub Long later summed up the situation: "They learned to live with what they had….A woman who knew how to do everything taught the newcomers and was far more important in the community than a president of the Chamber of Commerce."

These women, like many of their other neighbors, hoped to prove up on their claim while having a few years of successful harvests. At that point, most homesteaders probably intended to sell their land for a tidy profit. Instead, the dry farmers’ hopes were dashed by returning drought and killing frosts, as well as by plunging crop prices at the end of World War I. As a result, the surge of homesteaders in the High Desert quickly ebbed.

Between 1910 and 1920, the exodus of dry farmers from the region resulted in a nearly 20 percent decline in Lake County’s population. A few homesteaders stayed on, making a go of it as ranchers, but most left, some finding work in the sawmills of Bend, others in the cities on the West Coast. Abandoned homesteads remained as federal rangeland or were bought up by local ranchers for the price of back taxes. Since 1920, cattle have grazed where people once claimed their own little piece of “free land.”

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

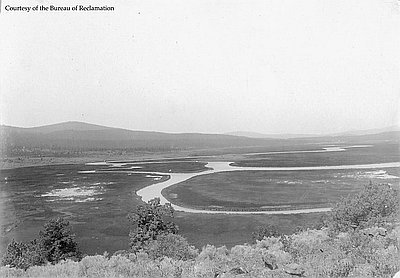

Abandoned Ranch, Christmas Valley, 1963

This photograph was taken in April 1963 by Oregon Journal photographer Al Monner. It shows an abandoned ranch in southeastern Oregon’s Christmas Valley. During the 1910s, hundreds of …

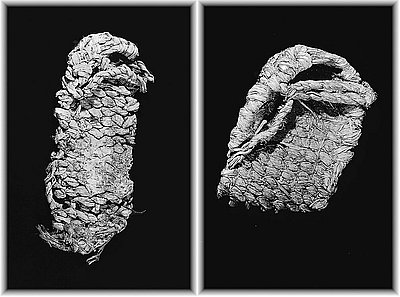

Multiple Warp Sandals

These sandals, featured in the Oregon Historical Society's exhibit "Oregon My Oregon," belonged to people living in the northern Great Basin up to 9,200 years ago. They are in the style …