The First Arrivals

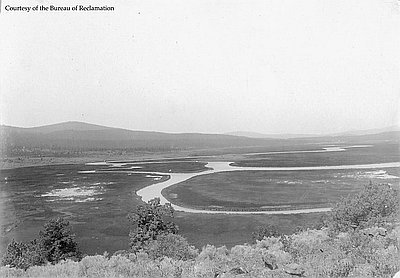

The first people moved into southeastern Oregon between about 13,000 and 10,000 years ago. By that time, the glaciers had melted into small remnants, and many of the great Ice Age lakes had begun to shrink into marshes, wetlands, and shallow lakes rich with plants and animals. These first Oregonians most likely had arrived in North America by way of a broad land bridge that stretched from Siberia to Alaska.

We know about peoples’ presence in southeastern Oregon from excavations in Paisley Caves in Lake County, where human coprolite (feces) has been radiocarbon-dated to 14,000 years before the present. Later, Paleo-Indian hunters chipped distinctive hunting tools on the shores of Alkali Lake, where archaeological excavations at the Dietz Site during the 1980s and 1990s yielded fluted Clovis-style obsidian projectile points, weapons that almost certainly were used to hunt the great Ice Age mammals. Farther north in Lake County, investigations of a shallow cave at Fort Rock produced tantalizing evidence of human presence well over 10,000 years before the present. When occupied, both of these sites would have been at the edges of large, shallow, freshwater lakes whose reed-choked shores attracted flocks of waterfowl.

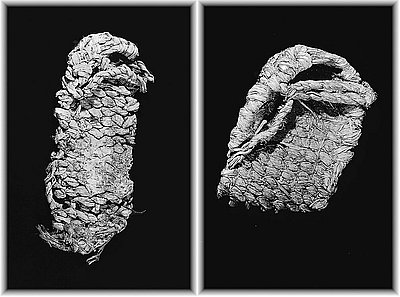

As climate change and other factors killed off Ice Age mammals, the people of southeastern Oregon adapted. Fluted points gave way to smaller, stemmed projectile points used for hunting bighorn sheep, elk, deer, and antelope. Lakeshore environments provided tule reeds and other plant materials for baskets, mats, and clothing. Fort Rock Cave is known for its cache of sagebrush-bark sandals, which have been radiocarbon-dated to 9,000 years before the present.

Even with the end of the Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago, the region’s landscape remained sensitive to changes in precipitation and temperature. Beginning about 8,000 years ago and lasting for approximately 4,000 years, a hotter and drier climatic cycle in what is now the American West caused most of the northern Great Basin’s lakes to disappear. Increased evaporation rates and changing habitats during this Hypsithermal period apparently led some Native people to concentrate in the uplands, near springs and other dependable water sources. They adapted to the change with ingenuity and resilience, using hunting blinds and cooperative game drives to take down large numbers of animals and weaving watertight basketry in which food could be boiled with heated stones.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

News Article, Lake County

This 1909 article in the Lakeview Examiner reported that 1,694,354 acres of the surveyed land in Lake County was still “unappropriated.” The article was part of a larger promotion …

Multiple Warp Sandals

These sandals, featured in the Oregon Historical Society's exhibit "Oregon My Oregon," belonged to people living in the northern Great Basin up to 9,200 years ago. They are in the style …