Journalists and other commentators first began using the term “New West” in the 1980s. It referred to the rapidly changing face of the American West, to its skyrocketing rate of urbanization—to the growing sophistication, affluence, and political power of its cities and suburbs—coupled with both a sharp decline in its older, commodity-based, rural economies and the meteoric rise of its high-technology and financial centers as major players in the global marketplace. In contrast, after a modest growth spurt during the 1950s, almost all of southeastern Oregon’s established towns either grew very slightly or actually declined in population throughout the 1960s and 1970s, a trend that has continued to the present time. The high desert is hardly a major participant in the New West. Malheur County’s Jordan Valley has steadily lost population over most decades since 1920.

The New West’s evolving and highly competitive economy has been tough on family ranchers and others who long prided themselves as personifying “rugged individualism.” With the ebbing political influence of rural areas like southeastern Oregon, representatives of the federal government—such as Forest Service rangers and BLM managers—took on something of a “black hat” role for at least some hard-pressed ranchers and others during the era’s so-called Sagebrush Rebellion, during which some people challenged the federal government’s right to manage public lands for any goals other than the direct economic benefit of local residents. In direct opposition to long-established constitutional policy, well-established case law, and continuing defeats in court, a few such individuals continued to hold on to the faint hope of converting federal grazing allotments and permits into iron-clad, non-negotiable “private property rights.”

Dramatic drops in the availability of federal and private timber in the region have posed a major burden on the high desert’s two biggest towns, Burns-Hines and Lakeview. Timber harvest levels on nearby national forests declined during the 1980s and 1990s. Harney County’s once busy railroad mill at Hines, purchased by the Snow Mountain Lumber Company in 1983, limped along for a couple more years. The logging railroad from Burns north to the little company town of Seneca had been abandoned and torn up prior to 1975, and most of the spur line linking Burns to the main railroad line on the Snake River suffered an identical fate not many years later. Most of the old Hines mill buildings have been torn down.

In Lake County, when the Oregon-Nevada-California Railroad’s owners threatened its abandonment in 1985, the county board of commissioners took a big gamble and purchased the old O-N-C line that ran south to Alturas, California, which had long-before been converted to standard-gauge track. Lakeview’s Fremont Sawmill, which dates to the postwar boom years and benefited in part from the Forest Service’s 1950s to 1970s implementation of special “sustained-yield unit” policies on much of the Fremont National Forest, continues in operation. With the O-N-C tracks still open for traffic, Lakeview’s mill continues to turn out wood products that are shipped entirely by rail to distant wholesale buyers.

The author acknowledges Bill Cannon, Mike Hanley IV, Don Hann, John Kaiser, and Don Rotell, who each provided information that is scattered through several paragraphs in this section.

In contrast to grazing and timber, federal activity not related to natural resource management has shriveled to almost nothing in the high desert. During the waning years of the Cold War in the late 1980s, the Department of Defense began building an ultra-high-technology “back-scatter” radar installation, which would have tracked the minutest of signals emitted from the ocean depths or the highest ionosphere, on the east edge of the Christmas Lake Valley. However, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, work on the unfinished facility halted in 1992, with only a skeleton crew of security guards patrolling the strange-looking complex of wires and antennae, clearly visible from the Christmas Valley-to-Wagontire road. Jet-fighter pilots, most of them flying out of southwestern Idaho’s Mountain Home Air Force Base or the Air National Guard installation at Kingsley Field near Klamath Falls, Oregon, continue to break the sound barrier on training flights over usually silent desert horizons, but the current U.S. military presence in southeastern Oregon remains only occasional and brief.

Absentee-owned ranching operations—whether run as corporate tax-deductions or for other purposes—returned to the Oregon high desert during the 1980s and 1990s. Although large absentee-owned operations had never been entirely missing from the region, millionaire businessmen purchased big spreads during these years. H.J. Simplot, for example, the “Idaho Potato King,” took over northwestern Lake County’s venerable ZX Ranch.

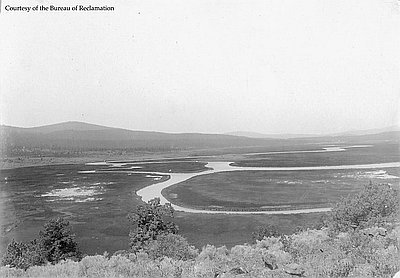

Smaller, owner-run ranches still dominate such areas as Warner Valley and the eastern foot of Steens Mountain, where every sizable natural spring along the mountain’s base is marked by a ranch with its house, barn, sheds, and other buildings sheltered from the wind by a perimeter of tall Mormon poplars. Raising cattle remains the region’s economic mainstay, and, despite mounting problems presented by cyclic national overproduction, cheaper imported beef, southeastern Oregon rangeland’s low carrying capacity and low profit margins, and other market factors, it will likely remain so for many years to come.

Somewhat similar to the brief borax-mining operations in southeastern Harney County’s Alvord Basin a century ago, an unusual form of mining occurred during recent years in Lake County’s Christmas Lake Valley. The Oil-Dri Company quarried tons of diatomite, an ancient but absorbent lakebed sediment; it is packaged and sold it as floor-cleaning janitorial material and as “kitty litter,” an operation that has since closed down. In southern Lake County, Cornerstone Industrial Minerals mines perlite, a form of volcanic glass that is processed and shipped from Lakeview for use in potting soil, insulation, and tile manufacturing. The very limited active mining on public lands in the high desert includes products such as semiprecious opal and “sunstones” for jewelry, and black and green obsidian, quarried for decorative uses.

Some early hints of potential “New West”-style, tourism-oriented economic success have appeared. The historic general store at tiny Adel has benefited not only from traffic along that lonely stretch of Highway 140 but also from its “step back in time” interior. Near the Malheur Wildlife refuge, the restored 1898 Diamond Hotel, in the ranching hamlet of the same name, does a thriving seasonal business with high-desert tourists. In the southern Blitzen Valley, the magnificent scenery and recreation opportunities of the nearby Steens Mountain Wilderness have resulted in a steady boom for the little community of Frenchglen—permanent population less than fifteen. The rustic Frenchglen Hotel, now a state-owned, privately leased “cowboy hotel,” serves numerous guests each season. Both the Diamond and Frenchglen hotels provide convivial boardinghouse-style meals, at which a birder from New York might converse across the table with a trophy hunter from Dallas. In 2000, enterprising Frenchglen residents even opened a summertime espresso stand in their front yard, directly across the road from the hotel and its neighboring restaurant/saloon. To the southeast, the desolate beauty and challenging whitewater of Owyhee Canyon brings rafters and kayakers to southern Malheur County; most of them “put in” on the Owyhee River near the grandiosely named hamlet of Rome.

Heritage tourism, focused on architectural treasures, has begun. Pete French’s unique “Round Barn” in Harney County’s Diamond Valley, once used by him and his buckaroos to break horses during high desert winters, has been restored by historic preservation teams from the University of Oregon’s School of Architecture. Despite its isolation, some visitors make the pilgrimage to admire the barn’s massive juniper rafters and carefully coursed stone walls; a large privately run visitor center is situated nearby. A federal grant stabilized and repaired Jordan Valley’s stone-masonry, Basque-built pelota handball court, returning this important historic site to a place where the ancient game can actually again be played.

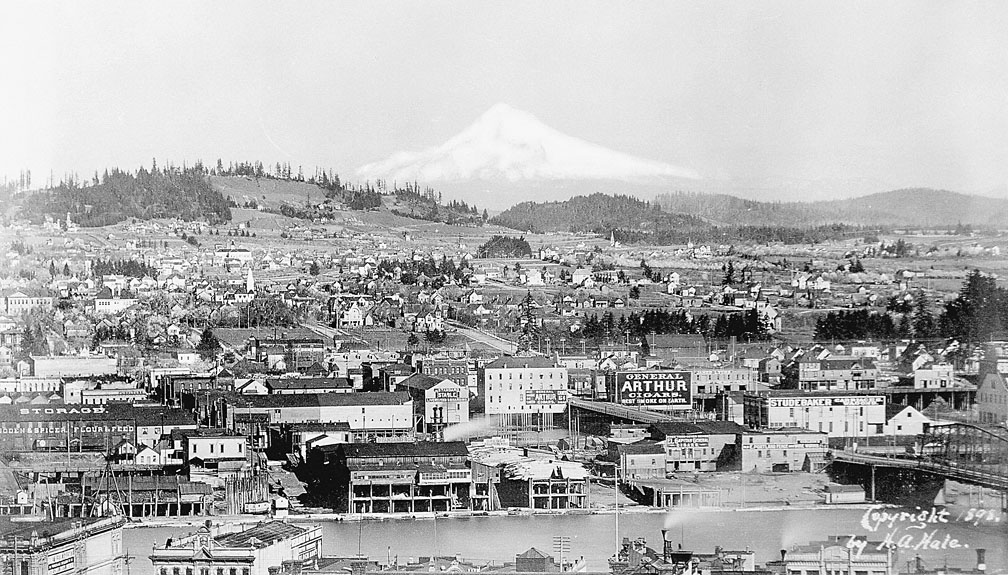

The main street of Burns retains many stone-masonry structures from the early twentieth century; a stroll along alleys behind many of the town’s brick-fronted commercial buildings shows the saw-and-chisel marks dating from when the just-quarried volcanic tuff was still soft and easily carved into blocks. Downtown Lakeview similarly remains an unpolished jewel of historic high desert architecture. Proud of having the oldest rodeo in the Northwest, the “Tallest Town in Oregon”—elevation 4,800 feet above sea level—may yet experience something of a commercial renaissance. In 2000 Lake County officials swapped land with the Forest Service to acquire the very modest, 240-acre Warner Canyon Ski Area, in the Warner Mountains near Lakeview. Just south of Lakeview and literally a stone’s throw from the California border, a small family business at New Pine Creek produces wine and other specialty products from an orchard of native Klamath plums, a wild fruit that Klamath and Northern Paiute Natives once eagerly harvested from mountain groves each autumn.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised, 2014.