The Great Depression

The Great Depression was, in part, a result of overproduction during the late 1920s. Lumber, food crops, livestock, and other products glutted the nation’s markets, and prices plummeted. Southeastern Oregon was particularly hard hit. Lumber mills cut production, wages, and hours and then jobs. Expecting the 1920s boom times to continue, Portland investors had begun building a large concrete structure at Hines, the Ponderosa Hotel, just a few months before the Wall Street crash halted the project. Some ranchers had to kill large portions of their herds to weather the hard times. A portion of the region even experienced its own dust bowl, caused by a natural drought, overgrazing, and deep plowing from the dry-farming experiment.

Most private investment capital in southeastern Oregon evaporated entirely, but the federal government stayed on. During this period, the federal presence became a more important actor in the High Desert economy. Not since the U.S. Army campaigns of the 1860s had decisions in the nation’s capital carried so much weight in the region’s affairs.

Federal dollars constructed or improved Highway 20 and other highways during the 1930s, putting local men to work. Federal dollars and work programs also built art deco post offices in Lakeview and Burns. But most New Deal expenditures in southeastern Oregon supported public land management and natural resource conservation efforts. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) brought hundreds of unemployed men from throughout the nation to the High Desert. Living in military-like camps, CCC workers fought range fires, strung miles of fence, improved irrigation drainage, constructed roads, and built striking and lasting examples of stone-masonry architecture, including the headquarters structures at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge and Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge.

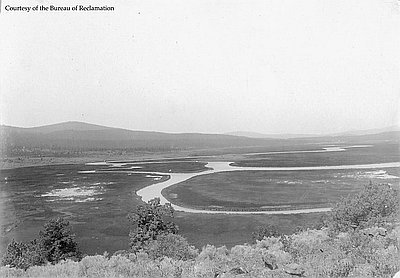

Thirty years earlier, in 1908, Theodore Roosevelt had created the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge on the shores of waterfowl-rich Malheur Lake to help protect snowy egrets and horned grebes from decimation by plume hunters. The refuge, under the watchful eye of Oregon ornithologist and wildlife conservationist William Finley, helped end the efforts of local ranchers and speculators to drain the lake and reclaim the lakebed. Augmented in 1934 by purchase of Pete French’s P Ranch on the Blitzen River, the refuge remains a vital stopping place for migratory geese, ducks, swans, cranes, and other birds dependent on the desert oasis. The Hart Mountain refuge, established in the 1930s, provided summer range for the dwindling herds of pronghorn antelope.

During the mid 1930s, as scores of deserted dry-farm homestead cabins weathered, leaning with the winter winds and then collapsing, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) initiated the Fort Rock Valley Resettlement and Land Utilization Project. The USDA bought up marginal and poorly irrigated acres from hard-pressed hay farmers in the Fort Rock and Christmas Lake areas and returned the land to the public domain as cattle range. Much of this effort, however, indirectly benefited the owners of the huge ZX Ranch, not the small, locally owned livestock operations. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 finally closed the public domain to homesteading, created the U.S. Grazing Service (which became part of the Bureau of Land Management after World War II), and brought a measure of rational, long-term range management to the region. As a direct result of the Taylor Grazing Act, sheep numbers declined, never to return to significance on public lands in southeastern Oregon.

By the closing years of the Great Depression, many High Desert residents distrusted the federal government’s increasing involvement in the region’s affairs, while also welcoming its financial support—and it was exceptionally generous, given the high per-capita expenditures in southeastern Oregon. New Deal programs significantly lessened the harshness of the Depression in southeastern Oregon and left a lasting legacy of soil and wildlife conservation.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

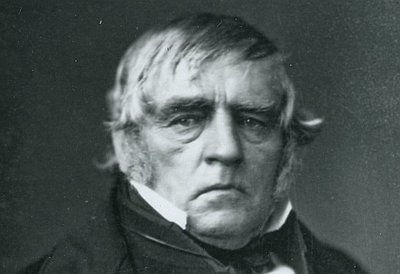

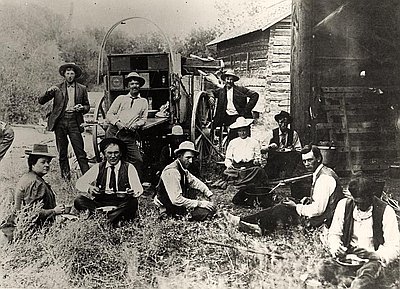

John William (Peter) French

This photograph of Peter French (seated to the left next to his wife Ella) was taken on his extensive land in Harney County--a land large enough to require …

Flock of Birds, Malheur Lake, 1908

This photograph was taken by William Finley in 1908. It shows a flock of birds, mostly American white pelicans with some gulls, flying over Malheur Lake, today part …

Lakeview & Goose Valley

Lakeview was named in 1876 for its view of Goose Lake, which is barely visible in the background of this photo (ca. 1910). At that time, Lakeview took …