Sawmills and Agricultural Structures

The sawmill was a defining symbol of Oregon for more than a century, and the mill was an iconic institution in hundreds of Oregon communities. The products of the mills went into building the communities’ houses and shops and schools, and through export sales they eventually supported the development of ports and railroads. Oregon became an economic colony dominated by the timber industry.

The sawmill at Fort Vancouver in 1827 was the forerunner of that colonial empire. The rapid influx of American settlers that began in the late 1830s precipitated a demand for sawn lumber and shingles. Ewing Young, an itinerant trader and adventurer who had settled on Chehalem Creek near present-day Newberg, was an early supplier. Young had achieved local prominence as one of the principals of the Willamette Cattle Company, which brought more than 600 head of cattle overland to Oregon from California in 1837 to supply the settlers with livestock. In 1838, Young began operating a small water-powered sawmill on his farmstead and selling the lumber to his neighbors.

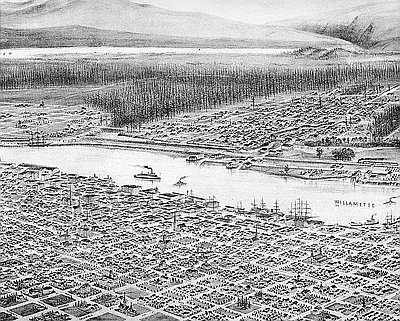

Other mills came soon after, including one on Willamette Falls at Oregon City in 1841 and Hunt’s Mill east of Astoria on the Columbia River in 1844. By 1850, dozens of mills were producing lumber and shingles in the Willamette Valley. The mills supplied not only local needs but also a developing export trade, notably to the Sandwich Islands—now Hawai’i. The California gold rush began affecting Oregon as early as 1848, and in the ensuing decade California’s voracious appetite for lumber was heavily fed by Oregon sawmills.

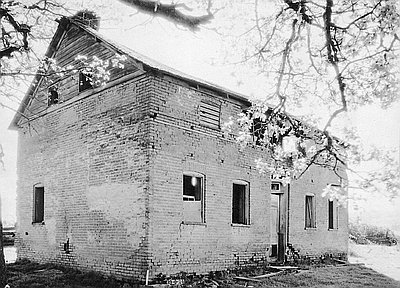

In the Willamette Valley, the discovery of clay that was suitable for brick-making led to some early experiments with brick construction. George Gay built a two-story brick farmhouse near Hopewell, not far from the Rev. Lee’s first Methodist mission, in about 1842. Two years later, George Abernethy built a brick store in Oregon City, and the Catholic church in St. Paul was constructed of brick in 1846. By the 1850s, small one- and two-story brick commercial buildings could be found in Portland, Salem, Jacksonville, and other towns. Brick was used to build woolen mills, churches, and public buildings such as fraternal halls and courthouses, but brick residences remained rare. Brick construction still required the substantial use of milled wood for interior supports, roof beams and trusses, floors and roofing, stairs, and interior walls. The sawmill was supplemented by other Oregon manufactories that transformed wood into shakes and shingles, balusters and newel posts, picture rails and baseboards, and decorative moldings.

Mining—especially of gold—was a significant Oregon enterprise beginning in the early 1850s in southern Oregon and in the 1860s in the northeastern part of the state. The first gold-mining activity at places such as Jacksonville and Auburn was in “placers” that required little in the way of buildings but that still demanded much construction work. Placer mining washed gold from river gravels, which often required moving stream channels to get to the gravel. A tremendous amount of pressurized water was needed for hydraulic placer mining, which left valleys denuded of soil and vegetation, heaped with miles of gravel rubble piles known as tailings. The hillsides were scarred with networks of hand-dug canals and tunnels that brought water from many miles away.

Lode mining of gold began in the 1860s, involving tunnels to remove ore, stamp mills to crush the ore, and concentrating works to begin the refining process. The need for imported heavy mining equipment helped make the fortunes of Oregon’s first major industrial enterprise, the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, which established a transportation network from Portland east to Lewiston, Idaho. The company rapidly constructed a fleet of steamboats, two portage railroads, and a network of wharves and warehouses at Portland, the Cascades, and The Dalles.

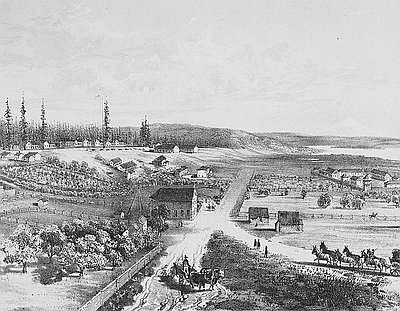

Self-sufficiency was often a goal of early Oregon farmers, but turning wheat into flour required milling. Mills required a sizable investment in a building, the water system to supply a waterwheel, specialized stones for grinding, and machinery. These gristmills also ground grains such as corn and oats, both for home consumption and for livestock feed. Gristmills soon dotted the Willamette Valley, for they needed to be constructed near farmers in order to minimize the wagon haulage over dirt roads. Small communities often developed around such mills. At Oregon City, Ashland—originally Ashland Mills—and Salem, the mills became the nucleus of a small city. At other places, such as Mulino and Boston Mills, the community remained small even though the need for the mill endured and it remained visually prominent on the landscape.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad …

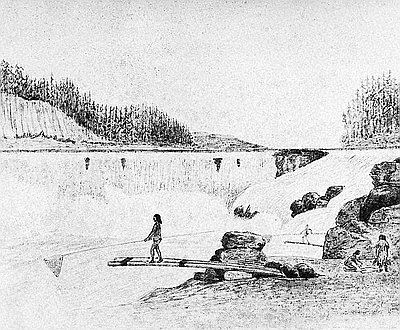

Indians Fish at Willamette Falls

Artist Joseph Drayton observed and sketched native life as one of several artists hired for a naval expedition led by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes from 1838 to 1842. Drayton’s …

George Gay House near Hopewell

The photograph above, taken for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1934, depicts the brick house built for George K. Gay near Hopewell in Yamhill County. The George …