The Public Face of Public Life

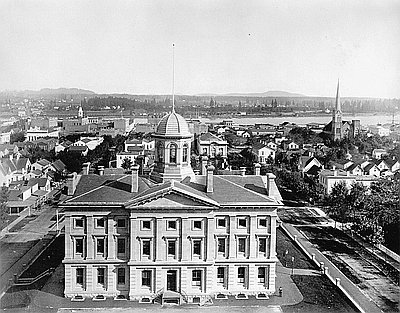

With a stable state and federal government and a growing population, Oregon boasted more and grander public buildings. The iconic state capitol in Salem designed by Portland architects Justus Krumbein and W. G. Gilbert in 1872-1873 was completed in 1876. Grand staircases and entrance porticoes were added in 1887-1888; and the dome, called for in the original plans, was completed in 1893. It was a grandiose public building with classical details in the Italianate style, built on a foundation of Oregon Umpqua sandstone. The main structure was of plastered brick with limestone trim. The capitol gave state government a headquarters designed by local architects and built of local materials: it was staid and dignified, somewhat stylish but not exceptional, appropriate to its time and place.

The rapid growth of the state’s population, particularly outside the Willamette Valley, led to the establishment of a number of new counties; ten of Oregon’s thirty-six counties were created between 1882 and 1899. In addition to new courthouses for new counties, the 1880s brought new courthouses in more established county seats. In 1883, for example, the old mining town of Jacksonville, which had been left a few miles off the new O&C Railroad, built a fancy two-story brick courthouse in the Italianate style as a sort of insurance policy against one of the upstart railroad towns capturing the county seat. The insurance worked until 1927, when Medford took the prize.

Elementary and high school education commonly occurred in wooden buildings, often of only one or two rooms. Still, they usually displayed some elements of architectural style, especially those in growing towns and cities. Buildings such as the Portland High School (1883), an elaborate wooden concoction in the Queen Anne style, and the Stick-style East Salem School made the point that citizens valued public education.

Higher education began with denominational schools as early as the 1840s—Willamette University in Salem and Pacific University in Forest Grove. Colleges proliferated in next several decades with such institutions as Albany College in Albany (1867; now Lewis & Clark College in Portland), the University of Oregon (1872), normal schools to train teachers—Monmouth, Ashland, Weston, Drain—and Oregon State University, which began in 1868 as the Methodist Church-sponsored Corvallis College. College buildings were designed to be imposing; Deady and Villard Halls at the University of Oregon and Marsh Hall at Pacific University are good examples.

Public institutions such as a mental hospital, a prison, and National Guard armories used architecture to emphasize their civic importance. The federal presence, capped by the Pioneer Courthouse in downtown Portland, also included customs houses in Astoria and Portland; Coast Guard stations at such points as Barview (Tillamook Bay), Charleston (Coos Bay), and Port Orford; and Fort Stevens at the mouth of the Columbia River. Navigational aids ranged from lighthouses such as Cape Blanco and Heceta Head, to jetties, which were built at the mouths of the Columbia, Nehalem, Alsea, Siuslaw, Umpqua, Coquille, Rogue, and Chetco rivers and at Tillamook, Yaquina, and Coos bays. Statehood brought with it a need to make public institutions visible and to make them visibly reflect dignity and civic pride.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

Pioneer Courthouse, 1875

When the courthouse at SW Fifth and Yamhill streets was built in 1875, it was considered by some residents to be too far away from the city. However, …

Portland High School, c. 1899

Photographer Edwin D. Jorgensen captured this image of Portland High School circa 1899. Constructed between 1883 and 1885, the building stood on the corner of SW Fourteenth and …