Modernism, Post-Modernism, Regionalism

In the later years of the twentieth century, the designs for commercial, office, and industrial buildings became increasingly bland and functional. Buildings rarely acknowledged regional differences in their design, either the impact of climate or the availability of local building materials. Steel, concrete, stucco, and glass largely replaced wood as building materials. The results could be dramatic and exciting. The Equitable Building was an instant landmark, while the Memorial Coliseum in Portland—1960, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill—is a shimmering glass box for sporting events.

An architectural marker in Oregon was the construction of the Portland Building (1980-1982), the first building conceived by noted American designer Michael Graves. Graves was a proponent of the design style known as Post-Modernism, a reaction to the sleek forms of the International style, and he had not yet applied its ideas to architecture. As expressed in the Portland Building, Post-Modernism was the application of color and stylized decoration—derived from Classical motifs—to an International style big concrete box. Hailed and denounced, the Portland Building made it clear that Oregon was up-to-the-minute in matters of architectural style and the awareness of celebrity architects.

From the 1970s, residential buildings in Oregon came from a national mold that made few references to historic periods or regional styles. While wood retained a strong presence in residential construction, it was used primarily in structural and support positions. Increasingly, it was present in the form of heavily manufactured materials such as chipboard, laminated beams, plywood, and cementous fiber board. The old-growth timber that had provided solid eight-by-eight beams was gone; the young trees that were now being harvested required additional manufacture to make useful products such as plywood and fiberboard. The use of solid wood siding, once the dominant exterior of Oregon buildings of all kinds, declined steeply.

Wood retains some of its old power in single-family residential construction, where once again style makes reference to historic motifs and traditional materials. A substantial proportion of residential work consists of manufactured houses and ahistorical McMansions, but alongside these are new designs for townhouses with Arts and Crafts details and smaller residences that evoke the Bungalow style. Automobile garages—which after World War II blossomed from one-car outbuildings to huge appendages that often overshadowed the house itself—have again been retreating to the side and rear of many newer houses.

At the end of the twentieth century, thousands of buildings and structures in Oregon, recent and historical, displayed the use of distinctive regional materials and were distinctive regional examples of various architectural styles. While interest in the development of a regional Pacific Northwest architecture seemed to have diminished, it certainly did not disappear. Concern for the protection and enhancement of Oregon’s resources, both the natural and those crafted by designers and builders, has continued to grow.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

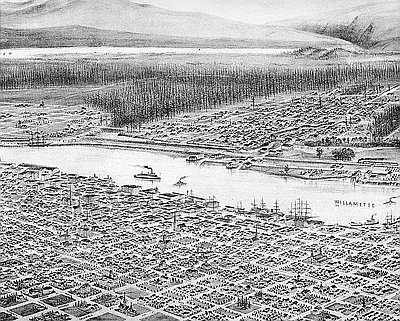

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary