The Portland Domination

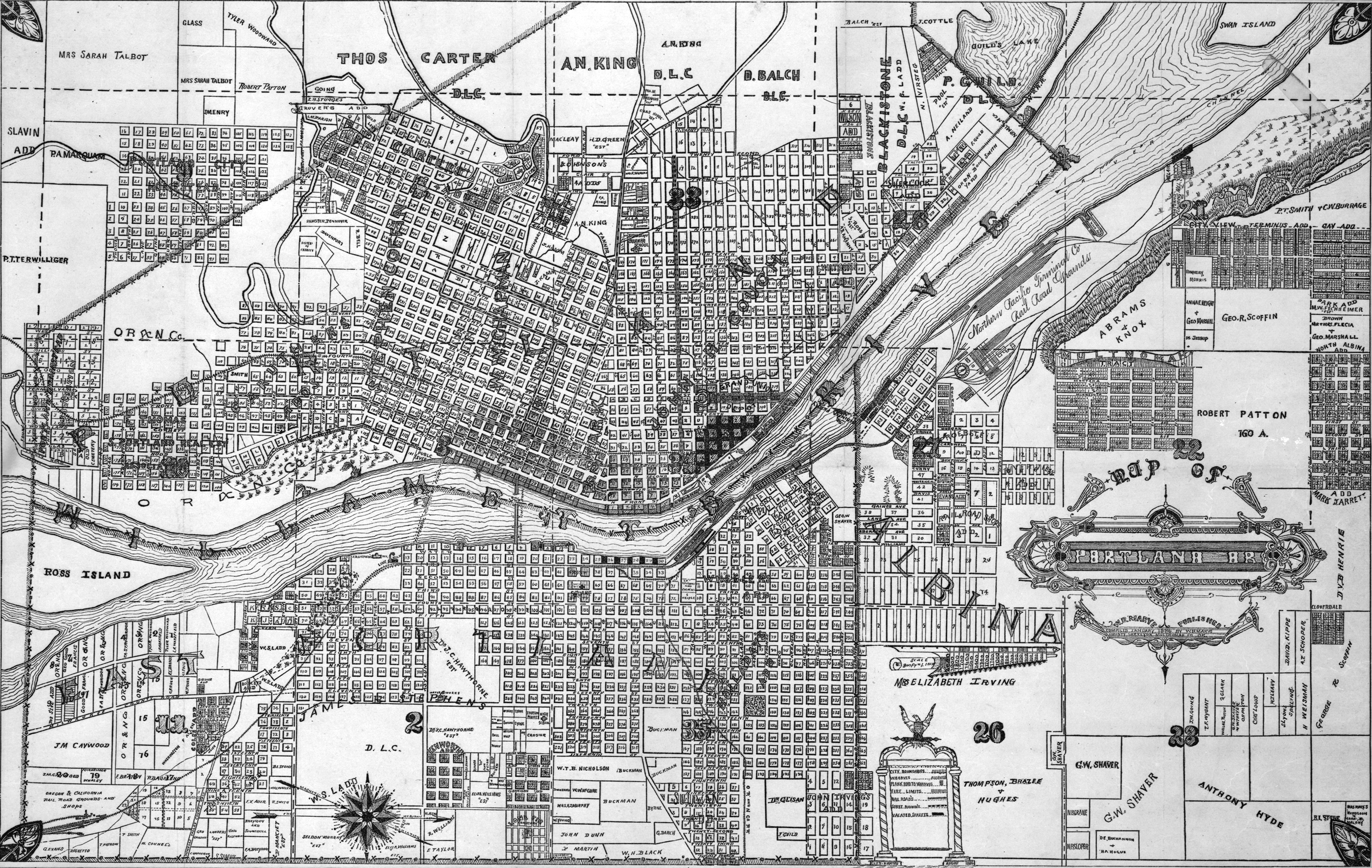

The population of Oregon swelled from 90,923 in 1870 to 413,536 in 1900. By 1900, two dozen communities had a population of 1,000 or more, and Portland’s population was 90,426. Portland had more than ten times the population of the state’s next most populous city, Astoria—population 8,381—and one in every four of the state’s residents lived there. While the state was characterized by small towns and rural agriculture, mining, and lumbering, the urban force of Portland exerted ever-greater influence. Its concentration of population and wealth meant that it was the first place to experience horsecars for transportation (1872) and electric lighting (1885).

Electricity also drove elevators, which made it economically feasible to construct buildings of more than three stories. Electric lighting and electric elevators combined with stone and brick materials to produce some grand Portland office buildings, such as the Richardsonian Romanesque Dekum Block (1892) and the Sherlock Building (ca. 1896) in the Renaissance revival style. Hotels, theaters, and that merchandising innovation, the department store, reached skyward in Portland during the 1890s.

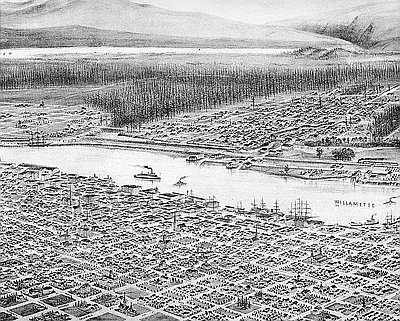

Electricity was also harnessed to transportation, and by 1889 Portland’s horsecars were being supplanted by electric-powered streetcars. Combined with the construction of the first bridges across the Willamette River, the streetcar helped centralize downtown Portland as the hub of shopping, entertainment, religion, and white-collar employment. Housing to accommodate newcomers to the city included downtown apartments and lodging and rooming houses as well as densely-sited single-family houses in south Portland and northwest of the downtown district. The streetcar—affordable, fast and easy to use—began to open up vast tracts on the east side of the Willamette River to suburban residential development.

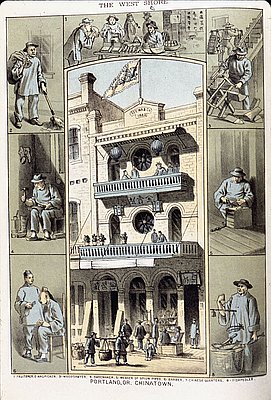

A small and densely built area of downtown Portland was its Chinatown. Chinese emigrants, most of them single men, constituted more than 10 percent of the city’s population in 1890. Small but distinctive enclaves of Chinese also lived in many other Oregon towns and cities, including Baker City, The Dalles, Astoria, John Day, and Jacksonville. Segregated areas for ethnic and religious groups, especially Chinese, Japanese, African American, Native American, Jewish, and Hispanic, were not uncommon. In cities as large as Portland, immigrant families tended to congregate, perhaps around a church or community hall. Portland’s Italian community centered on an area south of the downtown district, and on the east side of the Willamette River, where many engaged in market gardening. People of many other backgrounds also lived in these neighborhoods.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

Portland Chinatown, 1886

This color lithograph accompanied an article titled “A Night in Chinatown” in the October 1886 issue of West Shore, a Portland news and literary magazine. Several thousand Chinese …

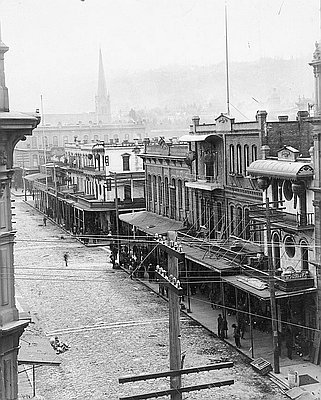

Chinatown, 1890s

This picture shows an unusually quiet intersection at the corner of southwest Second and Washington streets, just a few blocks from Chinatown’s heart at southwest Second and Alder. …

Morrison Street Bridge, 1889

The Morrison Street Bridge, built in 1887, served as the first bridge to connect the east and west banks of the Willamette River. The new connection spurred explosive …