The buildings and structures built by Oregon's inhabitants are evidence of how they lived, their industries and occupations, their creative impulses, and the natural resources of the land. Wooden Beams and Railroad Ties relates the history of Oregon as expressed through its built environment, from Chinook cedar lodges and missionary churches through covered bridges and fish canneries, to suburban houses, vacation resorts, and glass office towers. With a background in archival management of historical photographs, maps, and architectural plans, Richard Engeman was the public historian at the Oregon Historical Society until 2006.

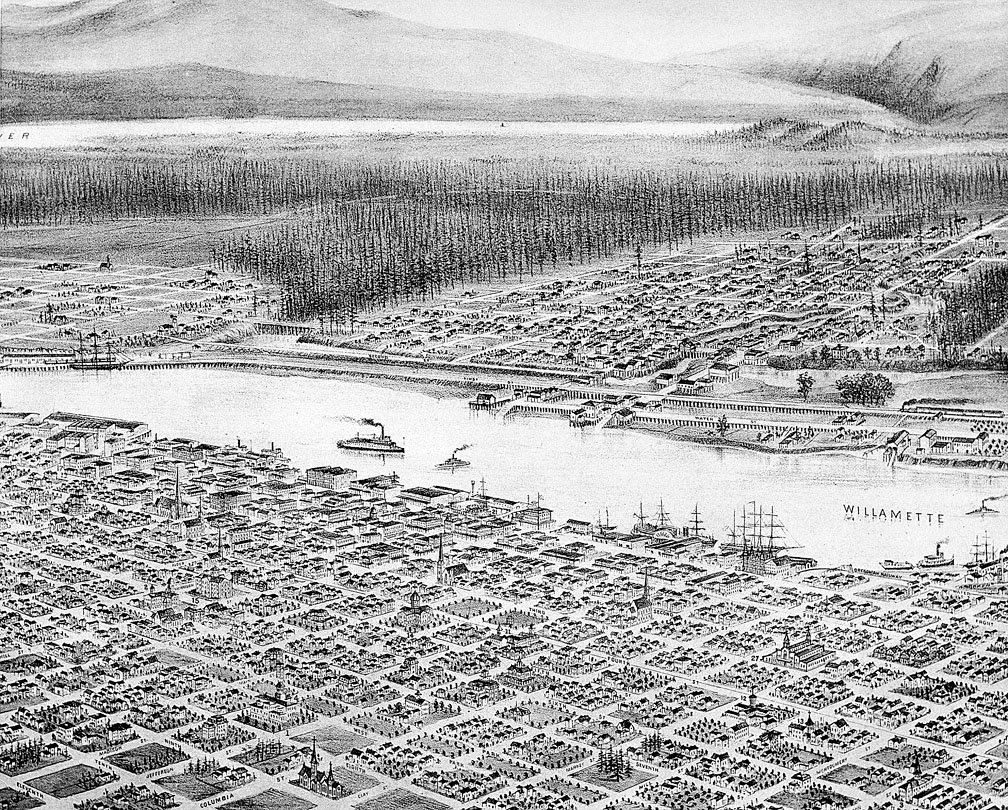

“Wooden Beams and Railroad Ties” is the history of the buildings and structures that Oregonians have constructed from the eighteenth century until today: the houses, mills, farms, shops, factories, dams, bridges, trails, and highways. What we see of the state’s built environment today is a layered, cumulative, concrete expression of Oregon’s history. This physical evidence is supplemented and enhanced by other historic representations, such as historical photographs, architectural plans and drawings, maps, and publications. Studying Oregon’s built environment involves examining all of these types of evidence.

Examining the history of what Oregonians have built makes several points. First, we can see how the state’s natural resources and geography affected our activities. Second, we can observe the dominant place that timber and wood products once had in the state’s economy and chart its decline and change. Third, we can observe how immigrants brought cultural traditions with them and adapted them to Oregon conditions. Finally, we can understand how, and how rapidly, Oregonians tracked and implemented esthetic ideas from elsewhere. Impressed onto the land—the form of buildings and dams, railroads and highways—is the physical impact human activity has had on the state.

The built environment—what we build and the materials we use to build it—is strongly influenced by geography and natural resources. The vast cedar and Douglas fir forests of the western slopes of the Cascade Mountains and the pine forests of central and northeastern Oregon, for example, led to the construction of sawmills and flumes, railroad trestles and splash dams. The structures were made of wood, but they were also part of the system of lumber production. The wooden splash dams, for example, impounded water that was released suddenly to float logs downstream to the mills.

The seemingly inexhaustible forests fostered the dominance of wood in building construction throughout Oregon well into the 1950s. The timber industry spawned mills, roads, and company towns, but it also has gone through major changes and declines. Other industries based on the state’s natural resources also have endured major changes, with the result that the number of structures related to such extractive enterprises as lumbering, mining, and fishing has greatly diminished.

At the same time, buildings that at one time would have been built of native wood and locally produced brick can now be built economically with imported brick, steel, concrete, glass, and other materials. Today, the state’s connection to its once-strong wood building tradition continues primarily through high-end architecturally designed residences, regional resorts that highlight local materials and historic references, and specialty wood products such as laminated beams.

Native American structures were dependent on local materials to fit local needs such as temporary camps and fishing platforms. The difficulty of preparing and transporting timber, for example, dictated the use of more immediately available materials for seasonal structures. The rapid influx of thousands of American immigrants beginning in the 1840s brought other building traditions and technologies to Oregon. Except for temporary dwellings, early immigrants rarely adapted Native building techniques and materials. Rather, they brought with them the technology for water- and steam-powered sawmills, techniques such as the hewn-frame and balloon-frame wooden construction systems, and esthetic concepts such as appropriate and fashionable architectural styles. These imported technologies, techniques, and ideas were changed and adapted in Oregon, but they generally paralleled national developments.

We can look at the built environment as an expression of Oregon’s geography and natural resources and as a reflection of cultural traditions and practices. It can tell us how we have treated and used resources, especially timber. Contemporary esthetic ideas are also apparent in our built environment, leaving the traces of a once-popular design situated amid more modern expressions. Wooden Beams and Railroad Ties provides a narrative framework for looking closely at and achieving a better understanding of Oregon’s historic built environment.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Two Teepees & a Stock Lean-to Umatilla Reservation Leeander Moorhouse Photo OrHi 93315

Indians along the Pacific Coast had the advantages of a mild climate and an abundance of easily worked cedar and other wood for building. Shelter provided relief from rain, wind, and cold and commonly took …

Euro-American settlers in the Willamette Valley of the 1830s and 1840s had no instructions to follow in selecting their farmland. They observed that prairie lands required little clearing before they could be tilled, and they …

Early Chainsaw OrHi 54484

The sawmill was a defining symbol of Oregon for more than a century, and the mill was an iconic institution in hundreds of Oregon communities. The products of the mills went into building the communities’ …

Marion County Courthouse P200

Much of the state’s development and population growth was concentrated along the railroad lines by the 1890s, but central and eastern Oregon were not unaffected. As the establishment of new county governments makes clear, thousands …

The dominance of Portland as the seat of the state’s wealth, power, and prestige was securely in place by 1910. Still, two-thirds of Oregonians lived outside the city’s immediate reach, on farms and ranches and …

Equitable Building & US Bank 1950 P200

A large number of wartime workers who had migrated to Oregon remained afterwards; Portland’s population escalated from 305,000 in 1940 to 374,000 ten years later. The workers often had come from the South and Midwest, …

Glossary

Architrave: in Classical architecture, the bottom third of the entablature. The term can also refer to the decorative molding around a window or door: a surround.

PioneerCourthouseSquareDesignP200

Abbott, Carl. Greater Portland: Urban Life and Landscape in the Pacific Northwest. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. Abbott, Carl. Portland: Planning, Politics, and Growth in a Twentieth-Century City. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983.