Law, Order, and Diversity

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California prompted the first massive migration across the Rocky Mountains in the late 1840s. Smaller gold discoveries drew thousands to northeastern Oregon in the 1860s.

Travelers in an 1845 wagon train had spread talk of a Lost Blue Bucket Mine, and a handful of prospectors searched for gold along the Burnt and John Day rivers in the 1850s. In 1861, near what would become Baker City, they at last found what they were looking for. News quickly spread, and the area’s white population multiplied.

The mining boom began in Auburn, where the first discoveries were made. Canyon City quickly followed. Both towns soon had several thousand residents, and smaller centers emerged at places such as Granite and Sumpter in Grant and Baker counties.

These early miners practiced placer mining: extracting flakes or nuggets of gold from streams. They used pans or simple rockers in which water washed away relatively light sediments, leaving the heavier gold behind.

But as the gold became more scarce, miners had to use more sophisticated equipment to churn through gravels beneath streambeds or on hillsides. Washing away tons of gravels required moving water from up to one hundred miles away. The “Big Ditch” that powered hydraulic mining in Auburn cost about $225,000 to build, money provided by Portland backers of the Oregon Steam Navigation Company. Local people ran and funded most of the smaller hydraulic mines.

Other miners practiced lode mining by digging gold-bearing quartz ores from beneath the earth’s surface. Stamp mills crushed the quartz so that gold could be extracted from it. Like hydraulic mining, this required substantial investments in equipment. Lode mining began in 1862 near Baker City, and two years later ten stamp mills were constructed outside the growing city.

Mining and miners declined dramatically after the mid-1860s, though it would periodically rebound.

Like other western mining towns, Auburn, Canyon City, and smaller settlements were lively, often dangerous, places dominated by young, unattached men. A Salem newspaper in 1863 referred to “the Fall fights” in Canyon City. Homicides were relatively common in and around gold towns, and a man named Spanish Tom was lynched by an Auburn mob after he killed two men in a dispute over a card game and, evidently, a racial slur. Robbery was also common, both in mining camps and towns and on the roads between them.

The mining towns struggled to impose order on their often unruly inhabitants. In the early 1860s, Wasco County included everything east of the Cascade Mountains, and the early miners felt that they could not rely on officials located far away in The Dalles. Auburn residents passed their own code of laws in the summer of 1862. They were particularly concerned about mining practices—how much land one man could claim, for example—and maintaining order. The newly organized government tried and hanged a man for poisoning his partner.

As the lynching of Spanish Tom suggests, gold drew people from across North America. Mexicans commonly worked as packers but sometimes mined, as did a smattering of African Americans. Chinese miners soon arrived and, despite confronting prejudice in law and practice, multiplied. The Chinese persisted in areas that white miners dismissed as unprofitable. By 1870, after the rush had passed, they constituted a clear majority of eastern Oregon’s miners.

In the heyday of the gold rushes, however, the majority of miners were white, usually from the U.S., sometimes from western Europe. The appearance of schools and even ministers of the gospel did not crimp their style much. A pious miner in John Day in 1862 recorded that “loud talking, swearing, & laughter of the croud was kept up all day, . . . Such is a mining town.”

Few women made their way to eastern Oregon’s mines. Some wives accompanied their husbands, some women taught school, and others ran businesses—though not always ones considered moral. “The inducements to sacrifice everything manly and womanly on the alter of lust & shame are numerous,” observed an Auburn woman late in 1862.

Oregon’s mining populace became more diverse as the gold rushes played out. Some 1,250 Chinese lived in or near Canyon City in 1862, most having arrived by way of California. The Chinese were willing to work ground that their white counterparts considered marginal, and many of them continued mining after the great majority of whites departed. Others stayed, but moved into other occupations. The 1880 census for the John Day area recorded nine Chinese merchants and sixteen cooks, for example. But the region’s Chinese population fell precipitously in the 1880s and 1890s as placer mining continued to decline and the federal government cut immigration with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Chinese were vulnerable to white persecution. Oregon law stipulated that they pay special taxes or fees, and local sheriffs and courts seldom concerned themselves with theft from or harassment of the Chinese. In 1887 thirty were killed and robbed along the Snake River by whites who were never punished for the crime.

A few Chinese immigrants remained in the region by the mid-twentieth century, and the Kam Wah Chung & Company Museum in John Day remains as a reminder of these people’s broad influence.

The gold rush brought thousands of people to northeastern Oregon. The Columbia River remained a major artery, as steamboats plied its wide waters. The Oregon Steam Navigation Company carried about 10,500 passengers in 1861, 36,000 just three years later. Many of these travelers were bound for the Idaho gold fields, but others headed south into the interior of eastern Oregon. Such travelers often disembarked at Umatilla, eighty miles upriver from The Dalles. Umatilla boasted nearly two dozen saloons or gambling houses by 1865. The pack horses and mule trains were joined by freight wagons and stage coaches in the 1860s. Smaller towns like Mitchell grew up along the freight and stage lines.

Supplying the people looking for gold was a more certain business proposition than finding gold, and adventuresome entrepreneurs from the Willamette Valley and elsewhere moved to northeastern Oregon in the gold rushes’ wake. By the 1860s, cattle were worth twice as much east of the Cascade Mountains as west of it, a fact that prompted a movement of some 50,000 head up the Columbia River in the first eight months of 1862. Others drove their cattle over the mountains. Stockmen soon began keeping and breeding their cattle in Umatilla County and in mountain valleys throughout the region, though the harsh winters and the decline in mining eroded their profits.

Miners wanted bread with their meat, so farming expanded in the area’s valleys in the early 1860s. Some farmed along the Umatilla River west of Pendleton, and the valleys of the Grande Ronde also drew a few hardy homesteaders.

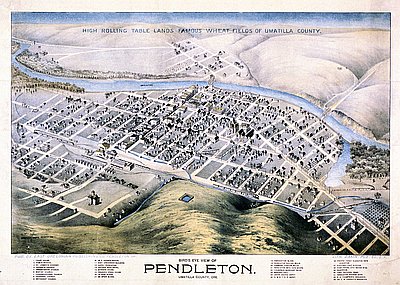

The towns that serviced the miners were both smaller and more durable than the mining towns. Umatilla shrank with the waning of the gold rush, but Pendleton, Baker City, and La Grande had more staying power, as they began to provide services to the ranching and farming hinterlands.

Yet the railroad and other developments would soon bring renewed volatility to northeastern Oregon.

© David Peterson del Mar, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

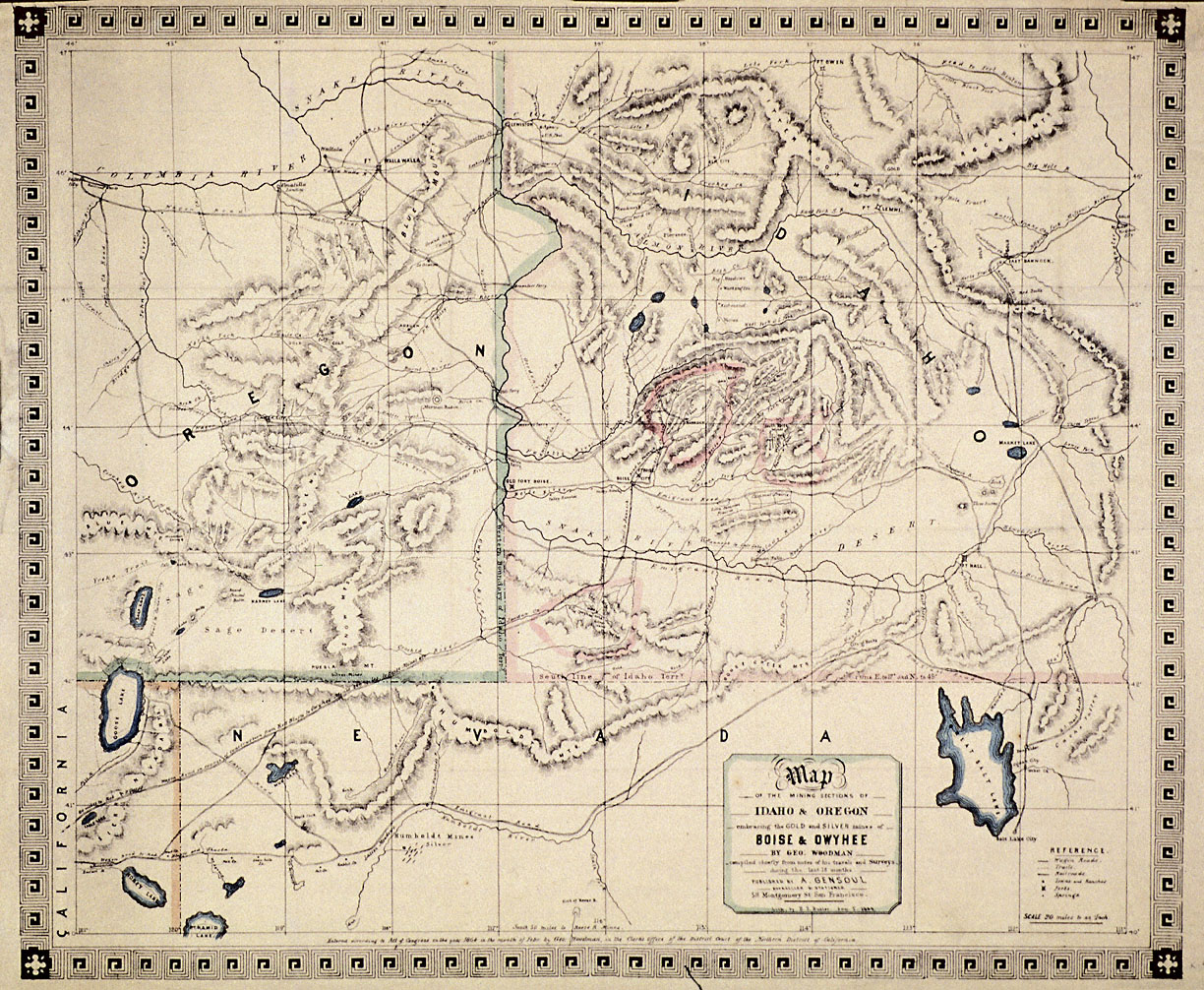

Mining Sections of Idaho and Oregon, 1864

This 1864 map of the mining sections of Idaho and eastern Oregon was drawn by George Woodman and published by San Francisco bookseller Adrien Gensoul. The map was …

Hydraulic Mine Operation, Jackson County

This photo, probably taken in the early 1910s, illustrates how thoroughly hydraulic mining reshaped the landscape of southwestern Oregon. Two massive monitors, also called giants, are shown blasting …

Auburn, Oregon, c.1861

This rare photograph shows part of the mining town of Auburn, located in northeastern Oregon about eight miles southwest of Baker City. The photo is dated 1861, but …