Hard Times and the New Deal

Drought arrived in northeastern Oregon in 1928 and remained until 1940. The Great Depression, the most severe economic crisis in the nation’s history, came a year after the drought and lasted about as long. Prices for wheat and other crops had been declining throughout the 1920s and now nosedived. Farmers west of the Cascades could at least feed themselves. But the drought made even that difficult in eastern Oregon. The combination of depression and drought drove hundreds of families from their farms in the 1930s.

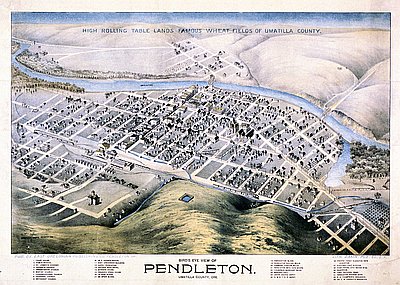

The decline in agriculture helps explain why five of the area’s ten counties suffered a net loss in population during the decade. The cities did better. La Grande declined slightly, but Baker City grew substantially. In 1930 the Hotel Baker, the “tallest building in Oregon east of the Cascade Mountains,” opened at a cost of nearly $3 million. Pendleton’s population swelled from less than 7,000 to nearly 9,000, as it joined Baker City as one of the ten largest cities in the state.

Ontario, once a shipping center for cattle, expanded along with Vale when a major irrigation project drew hundreds of farmers to the Snake River Valley in the 1930s. But establishing small, stable farms remained difficult. Four out of ten settlers in one study had sold out by the end of World War II, and another two out of ten had rented their farms. A family of nine who settled on Willow Creek in 1936 had to rely on public assistance, friends and relatives, and sent its children out to work in other people's homes or as laborers in sugar beet fields. They left after just three years.

As elsewhere across the nation, the Depression brought widespread unemployment to northeastern Oregon. The various New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration offered both short-term employment and public works that improved the area’s infrastructure, particularly roads. Ontario, John Day, and Fossil were connected to the rest of the state by a paved surface for the first time, and the treacherous road over the Blue Mountains, between Pendleton and La Grande, was at last fully paved.

But parts of the New Deal harmed the area’s residents. The Taylor Grazing Act tried to restore fragile grazing land by limiting access to herders, a move that drove many small operators, often Basques, out of business. Some sheep men were able to switch to cattle, the beginning of a trend that would continue long after World War II.

Residents of the Umatilla Indian Reservation were perhaps the most traditional indigenous people in the state, and they rejected the Indian Reorganization Act, the so-called Indian New Deal that promised increased self-government, in part because of long-standing distrust of the federal government. They continued to lease a large fraction of their remaining land to white farmers or ranchers.

© David Peterson del Mar, 200. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

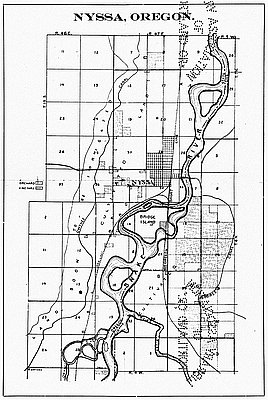

Facts about Snake River Valley at Nyssa, Oregon

This map is from a circa 1911 brochure promoting the “progressive and growing city” of Nyssa, located in northern Malheur County on the Idaho state line. The brochure …

Japanese Evacuee Tops Sugar Beets

This 1943 Oregonian photograph shows a Japanese American “evacuee” topping sugar beets in Nyssa, a small town on the Idaho state line in Malheur County. On February 19, …

Baker Community Hotel

The Portland office of architects Tourtellotte & Hummel, headquartered in Boise, Idaho, prepared this artist’s rendering of the Baker Community Hotel, which opened in 1929. The hotel was …