Cities and Work

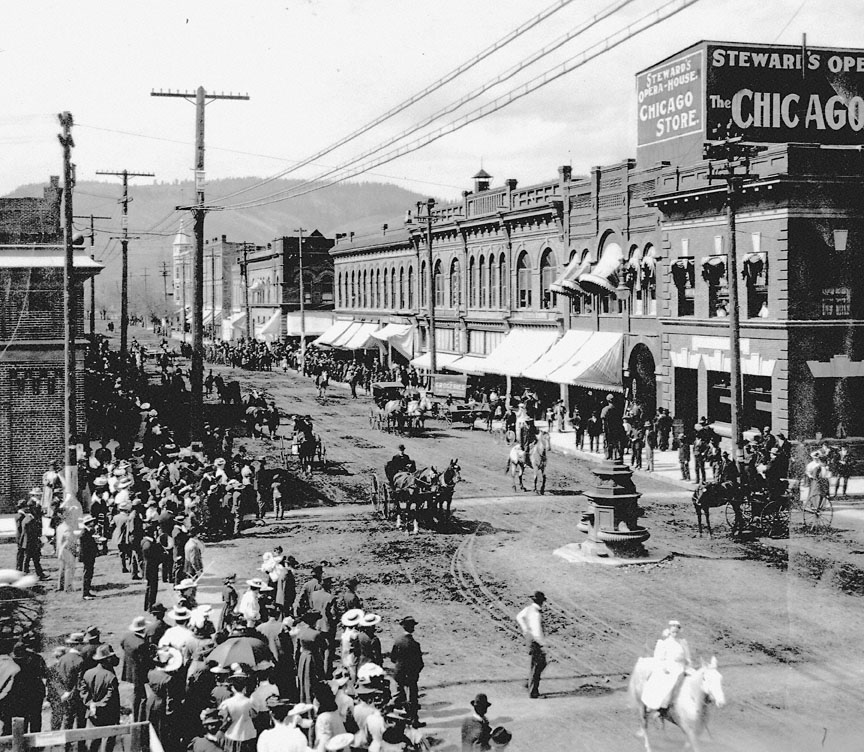

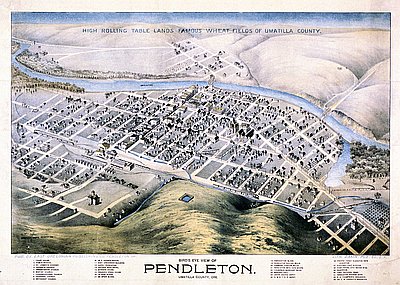

Although the main engines of northeastern Oregon’s economy lay in the countryside, the towns and cities that serviced these industries grew along with them. Sherman County’s small towns had three brick factories around the century’s turn. Pendleton boasted a mill that turned out 1,000 barrels of flour a day, as well as a foundry, machine shops, cigar factories, and two woolen mills. Electric lights and then telephones appeared in the area's cities in the 1890s.

Cultural sophistication accompanied urbanization. Baker City had a short-lived academy that opened in 1869. Not until the late 1880s, after the railroad’s arrival, did it offer three years of public high school. Enrollment in the La Grande’s school district rose from 131 in 1868 to 1,377 in 1900.

Prosperity freed more and more children for school in the early twentieth century. Teachers now attended normal schools (one opened in La Grande in 1929) and were more closely supervised than their nineteenth-century predecessors had been. These students, moreover, spent several more months in school than their parents had. A growing minority pursued their studies beyond eighth grade. By 1909 Baker City High School offered courses in Latin, German, physics, trigonometry, and psychology.

The prosperity that prompted more and more parents to send children to school rather than to work also presented new opportunities for women. Freed from much of the tedious and tiring work of subsistence agriculture, northeastern Oregon’s women were taking on the work of improving society as they moved from strictly domestic to public roles. Athena women had five churches and five lodges to choose from by the century's turn. More women earned wages, often as teachers. The great majority of wives did not work outside the home, but many of them joined the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Members of Elgin’s chapter circulated a petition to keep a saloon from opening and had persuaded the leaders of a church to discontinue the use of fermented wine at communion.

The waning of placer mining and the growth of more durable enterprises and towns made the northeastern Oregon of the 1890s much more stable and respectable than it had been in the 1860s. But the area’s growing farms attracted more than their share of young, unattached men, especially at harvest time, as did the ranching, logging, and mining industries. These workers often made things lively when they made their way to Pendleton, La Grande, or Baker City in search of wine, women, and song.

Northeastern Oregon continued to be plagued by more than its share of violence and crime. By 1897, Umatilla County, with less than 5 percent of Oregon’s population, contributed 11 percent of the residents of the state penitentiary. A year later an armed conflict between whites and Indians in Grant County left at least one dead on each side, and several wounded.

Prosperity was distributed very unevenly in the late nineteenth century, and growing inequality spawned discontent. Railroad owners charged higher rates than farmers expected and often ran roughshod over locals' sensibilities. A farmer near Heppner greased the tracks to express his disillusionment with these large transportation monopolies.

The area’s shifting, itinerant work force, the men who moved from farm to farm and town to town, was difficult to organize. The Knights of Labor, a national union touting a wide variety of reforms, appeared late in the century in Baker City, Pendleton, and La Grande as well as Huntington, which housed many workers for the Union Pacific Railroad. The Knights advocated reforms ranging from temperance to worker cooperatives, but in northeastern Oregon they focused much of their attention on excluding the area’s dwindling Chinese population from jobs that white men might fill. The organization had fractured by the century’s close.

If the railroad caused many of northeastern Oregon’s towns to boom, the automobile often had the opposite impact. As automobile ownership spread in the 1910s and 1920s farm families increasingly spent their free time and money in larger centers, where goods were cheaper and entertainment more varied. The main streets of towns like Summerville withered, as La Grande’s population grew from less than 3,000 in 1900 to over 8,000 in 1930.

The automobile was one of several national developments bringing northeastern Oregon into the nation’s cultural mainstream. Movie houses and popular magazines depicting sexy young actresses and actors proliferated across the region. Radios and phonographs spread jazz and other forms of popular music in the 1920s.

Nard Jones, a writer who lived in Weston, a town of about 600, depicted the impact of these powerful mediums in his realistic novel, Oregon Detour. His protagonist, a young woman named Etta, reflects that her husband and his friend dance and drink as “an imitation of something,” their attempt to mirror the “light-hearted adulteresses, libertines, drug fiends, and drunkards” that dominated popular culture.

Many members of Weston’s Methodist Church and Saturday Afternoon Club, which enhanced the town’s culture, were frustrated by the book’s preeminence on sex and sin. But few could honestly rebut that Jones’s take contained some truth.

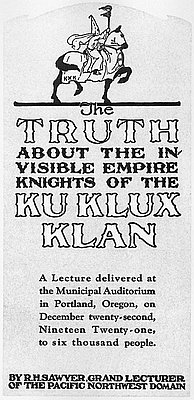

The Ku Klux Klan had become an important political and social organization across much of the United States by the early 1920s, and was particularly strong in Oregon. It had chapters in Pendleton and La Grande. La Grande’s chapter was a sort of club for white, native-born Protestants. They urged each other to do business with fellow Klan members and to avoid businesses run by Catholics or Jews. They criticized intemperance and other forms of immorality and were especially critical of La Grande's tiny African American and Chinese American communities.

It is no coincidence that the Klan appeared as northeastern Oregon was becoming more modern. It constituted an attempt by tradition-minded residents to control their communities.

But the area had been more dynamic than stable ever since whites had arrived, and the future would bring further change.

© David Peterson del Mar, 200. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

News Article, Passage of the Chinese Bill

The Willamette Farmer, a newspaper that was published weekly between 1869 and 1887, promoted Willamette Valley agriculture. This article reflects the sentiments of many Oregon farmers, merchants, and …

The Truth About the Ku Klux Klan, 1921

This pamphlet, whose title page is shown here, contained an edited version of “The Truth about the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” a pro-Klan lecture …

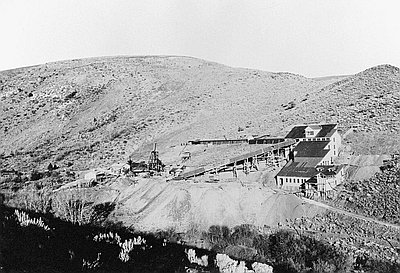

Mother Lode Mine, Baker County

This photograph shows the flotation mill of the Mother Lode Mine—also known as the Poorman/Balm Creek Mine—located about twenty miles northeast of Baker City. As the name suggests, …