Many indigenous people believe that their ancestors have always lived in the same place. Most archaeologists believe that humans arrived in the Americas between ten and twenty-five thousand years ago, when the Bering Strait that now separates Siberia from Alaska was above water. Discerning when Native people made their way to northeastern Oregon is difficult, as settlement no doubt focused on rivers that periodically flooded, washing away tools and other signs of habitation. But Native Americans certainly resided in or near the area 10,000 years ago. In 1996 a skeleton discovered near Kennewick, Washington, was dated as being over 9,000 years old.

Native populations grew with their capacity to know and utilize their environment. Political identities and boundaries shifted over several millennia in ways that we shall never completely understand. By 1750 A.D. the area was home to several thousand Cayuse, Umatilla, and Nez Perce peoples. The Paiute of the Great Basin sometimes crossed into the southern Plateau area and occasionally clashed with their northern neighbors.

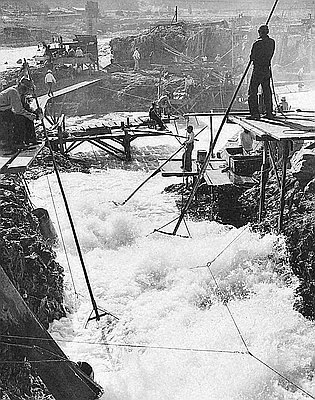

The peoples of the Columbia Plateau were relatively few in number and depended on a wide range of roots and bulbs, seeds, berries, greens, fish, and animals that required them to travel many miles to gather, hunt, and fish. A village group that wintered on the lower John Day River, sheltered from storms and living in mat-covered longhouses, would venture in the spring first to nearby ridges for roots and then southward to present-day Spray and beyond, searching for camas that would be stored for the winter. Summer brought them to the Columbia River and its major tributaries to fish and to mountain meadows to pick berries. Most hunting occurred in the fall, as men traveled into the hills and mountains. The Plateau peoples’ proximity to one of the region’s great trading marts, near present-day The Dalles, enabled them to acquire goods from far-away places. But local plants constituted the most important source for manufacturing tools. Hemp became string and netting, tule rushes became soft mats, and cedar roots were transformed into baskets.

The Plateau peoples’ modest levels of population and wealth made for societies characterized by general equality. Very few held slaves, and leaders relied heavily on the consent and support of their people. Women were seldom political leaders but commonly became shamans or healers, religious specialists. But all people were expected to learn the daily and annual rituals required to navigate in a world shaped by powerful spiritual forces. Like other indigenous groups, Plateau peoples put a great deal of emphasis on kinship and intra-group harmony. They traced their descent through both parents and spoke various dialects of Sahaptin that peoples across the region could understand.

Horses appeared on the Columbia Plateau in the early 1700s and quickly changed its economic, social, and political relations. They made it possible to travel and therefore hunt much farther afield, especially across the Rocky Mountains, where buffalo were thick. But horses also made these peoples much more vulnerable to raids from groups that lived several hundred miles away and who were acquiring firearms.

The Plateau peoples tried to protect themselves by giving more authority to war leaders, men who had grown wealthy and powerful by amassing hundreds of horses. Even as they eased hunting and travel, horses caused a widening gap between rich and poor and prompted warfare.

Smallpox preceded American and European exploration on the Columbia Plateau. It arrived in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and killed about one third of the populace. These deaths weakened the physical and psychological resources of Native peoples and prompted shamans and others concerned with the spirit world to find an explanation for the horrendous deaths.

Prophets announced that the world would soon end, that the living would soon be reunited with the dead, that strife and suffering would cease, and that this new, perfect world would be ushered in by the arrival of new, very different peoples.

At the turn of the nineteenth century the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Nez Perce found themselves reeling from losses inflicted by disease and raids but hopeful that these times of trouble would soon pass.

© David Peterson del Mar, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.