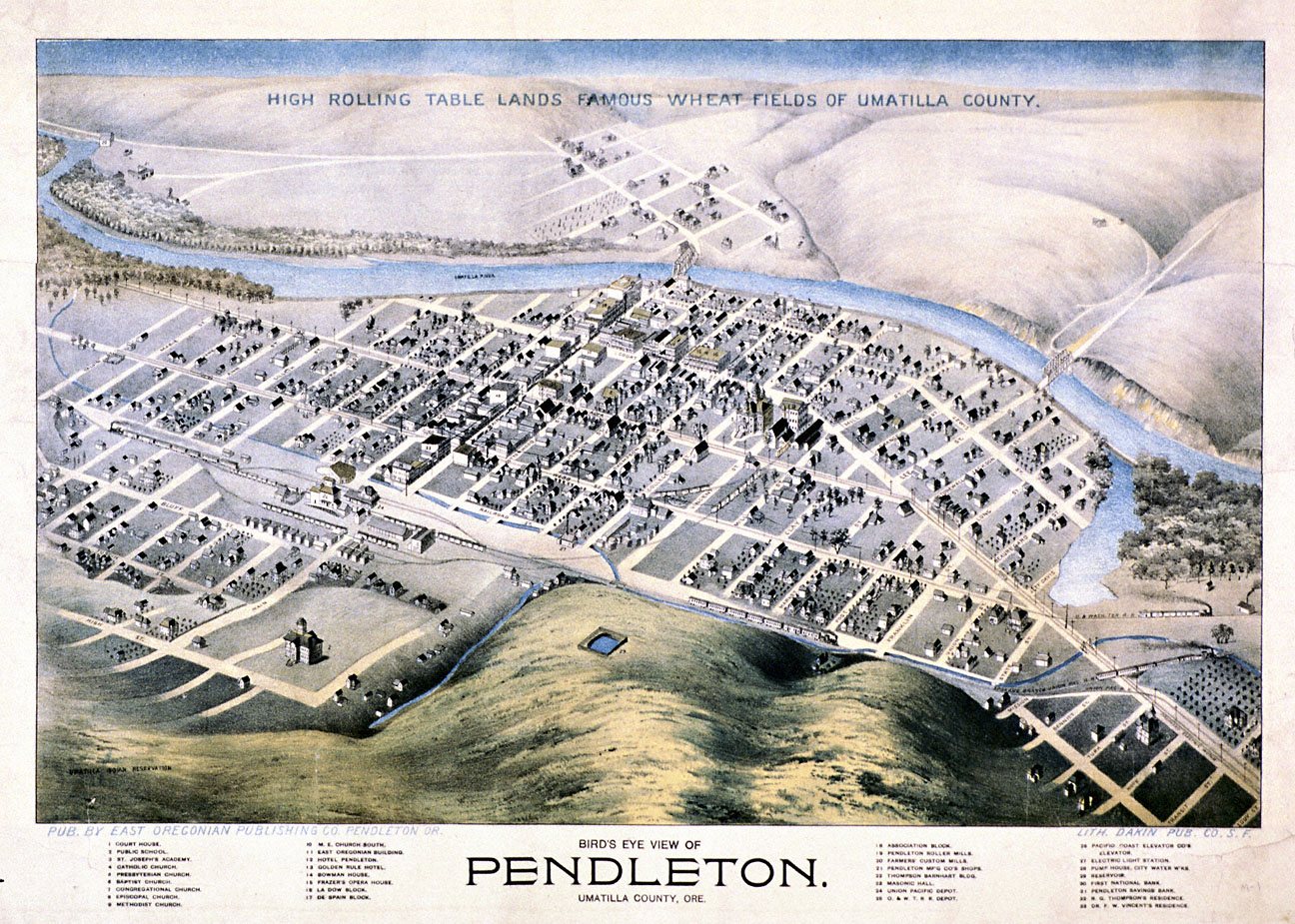

Northeastern Oregon—Grant, Baker, Union, Wallowa, Umatilla, Morrow, Gilliam, Sherman, and Wheeler counties, together with the Ontario/Vale/Nyssa area of Malheur County—is an often breath-taking place of mountains, valleys, and broad plateaus. With hot, dry summers and bone-chilling winters, it has never been an easy place to make a living.

The area’s rugged landscape has inspired loyalty from its residents, and its minerals, timber, and soils have drawn thousands of people since the 1860s. But its primary industries—mining, timber, and (often irrigated) farming have been volatile. In 2010, northeastern Oregon was home to less than 5 percent of Oregon’s population, and six of the area’s ten counties had fewer people than in 1920. Those determined to stay here have had to make their peace with a stark, beautiful place whose unstable economy has often been controlled by people and factors originating outside its borders.

Northeastern Oregon is an often breath-taking place of mountains, valleys, and broad plateaus. With hot, dry summers and bone-chilling winters, it has never been an easy place to make a living. Those determined to stay here have had to make their peace with a stark, beautiful place whose unstable economy has often been controlled by people and factors originating outside its borders. David Peterson del Mar teaches history classes for Portland State University, Oregon State University, and the University of Oregon and consults for several grants on teaching history in middle and high schools. He is the author of several books, including Oregon's Promise: An Interpretive History.

Mr Heinlein Issues Blanket & Tents to Paiutes P200

Many indigenous people believe that their ancestors have always lived in the same place. Most archaeologists believe that humans arrived in the Americas between ten and twenty-five thousand years ago, when the Bering Strait that …

031Warm Springs & Umatilla Scouts P200

We should not be surprised that the Nez Perce welcomed the emaciated members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who staggered into one of their camps in September 1804. The only resident to have dealt …

Miners Working Jacksonville Backyard OrHi 57124

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California prompted the first massive migration across the Rocky Mountains in the late 1840s. Smaller gold discoveries drew thousands to northeastern Oregon in the 1860s.

Aside from the Columbia River, northeast Oregon is not much blessed with navigable waterways. The high expense of moving goods over roads, particularly mountainous ones, often hamstrung development. Gold did not weigh much, and cattle …

Baker City between 1865 and 1870 M.M. Hazeltine Photograph OrHi 92

Drought arrived in northeastern Oregon in 1928 and remained until 1940. The Great Depression, the most severe economic crisis in the nation’s history, came a year after the drought and lasted about as long.

The long-standing trend toward larger and more capital-intensive farms in northeastern Oregon’s wheat belt has accelerated since World War II. New fertilizers and pesticides and disease-resistant strains increased yields. Mechanization continued.

Ed. Beckham, Stephen Dow. Oregon Indians: Voices from Two Centuries. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006. Ed. Berg, Laura. The First Oregonians. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 2007.