Asia at the Fair

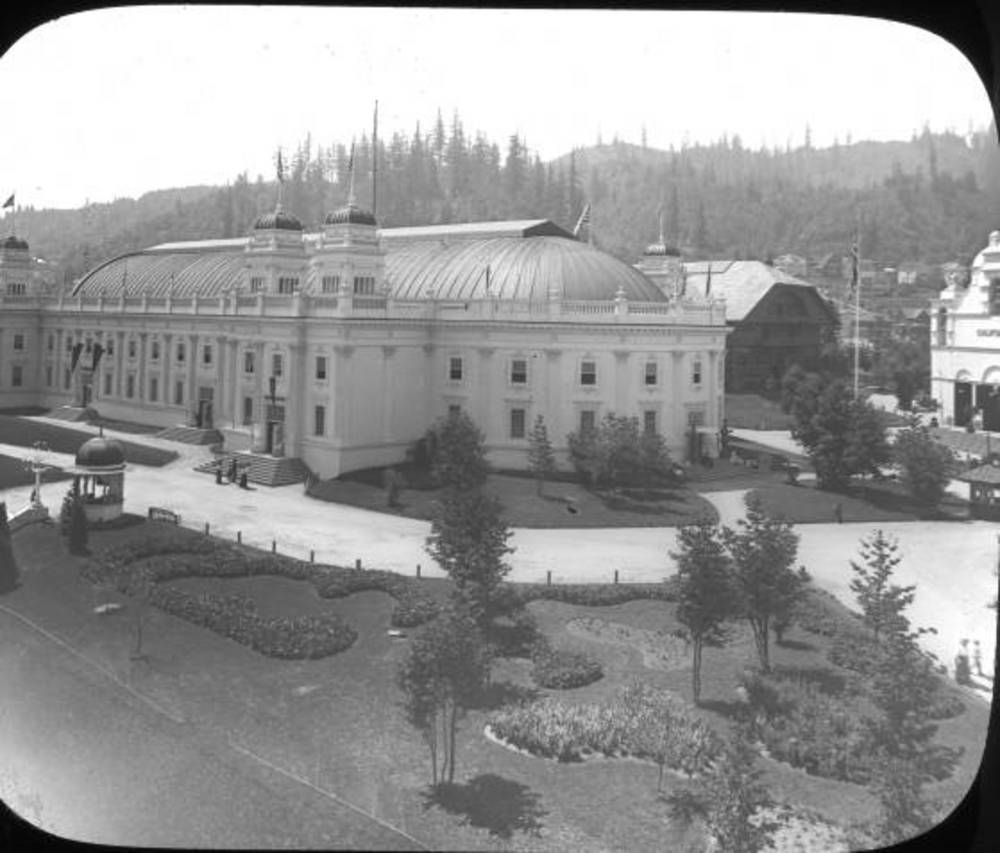

Lewis & Clark Expo, 1905. Lewis & Clark Expo, 1905.

Exposition visitors could walk through the 50,000 square feet of the Oriental Exhibits Building—the second most costly at the fair—to view the products of China, Turkey, Egypt, India, Ceylon, Siam, and Korea. Most of the Asian exhibits were actually put together by trading companies and importers who wanted to show off their carpets, textiles, and housewares to potential customers. China’s Shantung province did send an official exhibit to balance the low quality of some of the other Chinese products. But by far the largest Asian presence came from Japan. As a guide to the exhibits stated:

It is Japan which makes the Oriental part of the Fair really notable. She occupies more than half the space in the Oriental Building. It is understood that the Emperor, not quite satisfied with the excellent showing made last year at St. Louis, gave his commissioners instructions to outdo what was done at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition [in St. Louis].

In fact, the fair displayed the old image of quaint Japan represented by the traditional handiwork and household items with which many Americans were decorating their homes: bronze lanterns, porcelain, silk embroidery and hangings, dolls, metalware, cloisonne vases and boxes, carved ivory, lacquer work.

In sober fact, Japan in 1905 was far more than a producer of knickknacks. It had just defeated Russia in a war for the control of Manchuria in northern China, annihilating a Russian fleet and defeating Russian land armies in campaigns that anticipated World War I. Although it was fast becoming an industrial powerhouse and the major power in eastern Asia, Americans were slow to adjust their image of a Pacific rival. American opinion had favored the “plucky little Japs”—to quote one newspaper cartoon—in battling the barbaric Russian bear. The Feast of Lanterns, celebrated at the Exposition on August 31, included floats depicting the end of the Russo-Japanese War and the imperial throne. It was a reminder of the “great, progressive and enlightened Japan of today,” said the Oregonian.

“The whole fair,” said World’s Work, “is a successful effort to express . . . the natural richness of the country and its relative nearness to Asia.” Future world’s fairs on the West Coast would reiterate the same theme. Seattle staged the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1905. California celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal in 1915 with two expositions: the Panama-Pacific in San Francisco and the Panama-California in San Diego. A generation later, San Francisco’s Golden Gate Exposition of 1939-1940 offered an art deco introduction to the Pacific Ocean as an American Lake. The official style was “Pacific Basin,” meaning Incan, Thai, Cambodian, and Malayan elements laid on in Hollywood exuberance and painted in pastels. Two Towers of the East cast salmon and gold reflections on the Lake of All Nations. An eight-foot statue of “Pacifica” loomed over the Fountain of Western Waters. Visitors who watched the Pan American Airlines China Clipper take off outside the Hall of Air Transportation could visualize the American economic ambitions.

In fact, the San Francisco fair anticipated a much more complex set of American-Pacific relations. In the next few years, the Bay Area would become a teeming shipbuilding center and embarkation point for the war with Japan (1941-1945). Victory in 1945 put the western states in a different relationship with the Pacific Rim. Over the next half century, the U.S. would establish a permanent military presence in islands off the coast of Asia—Japan, Okinawa, Taiwan, the Philippines—and fight two more Pacific wars with North Korea and China (1950-1953) and North Vietnam (1963-1974).

The value of U.S. trade across the Pacific overtook the nation’s Atlantic trade in 1982. Oregon’s contribution to this seaborne trade is not much different than it was in 1850. The state exports great tonnages of regional raw materials: wood products from Washington, minerals from Wyoming, pre-cut French fries from Idaho, hay cubes from Wallowa County, wheat from Gilliam County, pears from Jackson County, and a host of other farm products. It imports Asian-made automobiles and miscellaneous manufactured goods. On the whole, Portland and Oregon’s smaller ports such as Coos Bay handle cargos with high tonnage but relatively low value compared to Seattle, Tacoma, Los Angeles, and Long Beach.

And the primary trading partners—just as Myers and Scott envisioned—are the nations of East Asia. In 1999, 24 percent of Oregon’s exports (measured by value) went to NAFTA neighbors Canada and Mexico. Three quarters of the remainder—the overseas shipments—went to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and elsewhere in Asia.

© Carl Abbott, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Central Vista, Lewis & Clark Centennial Expo

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition was the West Coast’s first worlds fair. This central vista shows the Foreign Exhibits Building on the left, and the Agricultural Palace on …

The Igorrote [sic] Tribe from the Philippines

This article was published in the Lewis and Clark Journal in October 1905. It discusses the exhibition of Igorot people at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition and …