Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair

One of Portland’s grandest parades started at the corner of Sixth and Montgomery streets at 10 a.m. on June 1, 1905. Mounted police led off, followed by marching bands, 2,000 National Guardsmen, and more police to bring up the rear. As the marchers trooped up Sixth, their ranks opened in front of the elegant Portland Hotel to make way for the carriage of Vice President Charles Fairbanks. Their destination was Northwest Portland and the inaugural ceremony for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, where the opening-day crowd of 40,000 could listen to a dozen long speeches about the importance of Portland and the first world’s fair on the West Coast.

Visitors who drifted away from the oratory discovered fairgrounds that encircled the shallow waters of Guild’s Lake, in the floodplain of the Willamette River. The formal layout of lath and plaster buildings imitated the Chicago fair of 1893. Exhibition buildings overlooked the lake from a low bluff. A wide staircase led downslope to “The Trail,” the amusement arcade where the wonders of the world were available for a dime or quarter. A Bridge of Nations connected the mainland to the U.S. government buildings, which showcased federal resource agencies. The whitewashed stucco of the buildings gleamed against the West Hills like “diamonds set in a coronet of emeralds.”

From June 1 through October 15, nearly 1.6 million people paid to see the first world’s fair on the Pacific Coast of North America. Four hundred thousand were from beyond the Pacific Northwest. They could attend high-minded conferences on education and civic affairs or participate in national conventions of librarians, social workers, physicians, and railroad conductors. They could inspect the exhibits of sixteen states and twenty-one foreign nations. They could fritter their money on “The Streets of Cairo” and the “Carnival of Venice.”

The city’s business leaders gave wholehearted support to planning and promoting the Exposition, for its purpose was a bigger and better Portland. It was an age when every ambitious city aspired to put on a national or international fair. The list already included Philadelphia, Atlanta, Nashville, Chicago, Omaha, Buffalo, and St. Louis; soon after the Portland fair would come events in Norfolk, Seattle, San Diego, and San Francisco. The fair was to show outside investors that Portland was a mature and “finished” city rather than a frontier town. It was also intended to give Portland an edge over upstart Seattle and confirm its role as a commercial center for the Pacific.

The Lewis and Clark fair offers a window into the city and state of a century past and its changes over the last hundred years. The motto over the entrance was “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way,” a direct celebration of the ongoing development of farming, forestry, and other resource industries that had fueled Oregon’s development since the fur trading days and would continue to do so through most of the twentieth century. The event’s official title was the “Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair,” striking another direct connection to the predicted links between Oregon and the Pacific Rim that have grown to such importance in the early twenty-first century. A re-enactment of the recent American victory at the Battle of Manila Bay on “Portland Day” expressed pride in the recent acquisition of an overseas empire but also raised the troubling question of which peoples—Asian, Pacific Islander, Indian, European—truly counted as “Oregonians” and “Americans.” And a huge electric sign on the West Hills that read “1905” not only showed off the kilowatt capacity of the Portland Railway, Light, and Power Company but also anticipated the importance of electricity and electronics in shaping the modern state.

© Carl Abbott, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Night View of the Lewis and Clark Fair

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition and Oriental Fair in Portland was illuminated at night by 100,000 lamps that outlined the graceful fair buildings, streets, and walkways. “No …

Central Vista, Lewis & Clark Centennial Expo

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition was the West Coast’s first worlds fair. This central vista shows the Foreign Exhibits Building on the left, and the Agricultural Palace on …

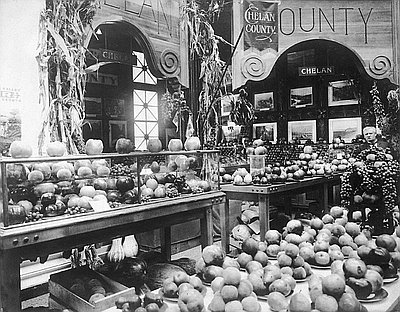

Chelan County Exhibit, 1905

This 1905 photograph shows Chelan County’s exhibit at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, held in Portland from June through October 1905. Proudly displayed is a cornucopia of …