Of course, not all the central Oregon ranches were small operations. The largest ranches in the 1870s and 1880s included the Baldwin ranch at Hay Creek, the Teal and Coleman ranch on Trout Creek, and the Farewell Bend Ranch on the Deschutes. The Hay Creek Ranch was especially famous for its superb stock of Merino and Rambouillet sheep. In 1880, John Y. Todd, who owned the Farewell Bend Ranch, drove 5,000 head of cattle collected from his ranch and that of a neighbor to market in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Around Buck Creek, in the upper Crooked River country, Bill Brown assembled holdings estimated at 140,000 acres of deeded and leased land. In 1917, Brown drove 10,000 head of his horses to market for the war in Europe. Other great central Oregon ranches included the Prineville Land and Livestock Company’s Big Muddy Ranch, the GI Ranch on the south fork of the Crooked River, and in later years the ranches of the Hudspeth Land and Livestock Company.

During the late 1870s, the cattle business began to fade as increased cattle production drove prices down. Kate Robbins estimated that 5,000 cattle had been sold from the Ochoco Valley in 1878. The prices had fallen to $10 for cows, and $12 to $20 for steers. Abner Robbins had paid $40 for cows with calves in 1871, and “thought he was doing well.” By 1880, 200,000 head of cattle had been driven east from Oregon and sold at liquidation prices. The winter of 1884 was especially severe throughout the West, killing tens of thousands of range cattle in deep snows.

In the wake of the cattle came the sheep. The Baldwin Ranch on Hay Creek ran 50,000 sheep at its peak in the 1880s, and the wool clip reached 500,000 pounds. Sheep herders summered their stock in the higher elevations of the Cascades then bought them down to lower elevations when the weather deteriorated. Alberta McCabe described the bands of sheep coming through Sisters in September of 1912: “the sheep have been coming through from the forest reserve by the thousands every day, and the dust was pretty bad. The herders go by on horse with half a dozen other horses with large packs on their backs following.”

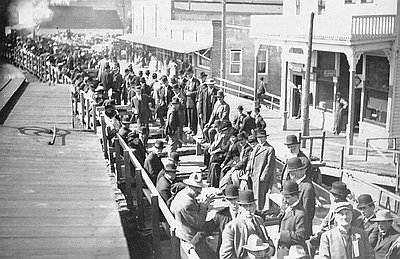

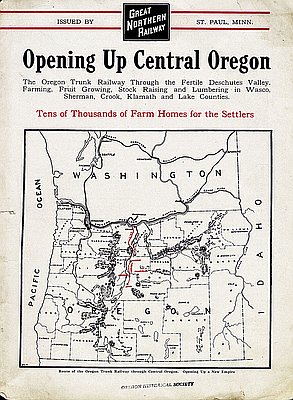

Shipping wool and lambs was difficult without rail transportation, and this did not reach the upper Deschutes country until 1911. The best rail connection after 1901 was Shaniko, a community built on the Deschutes Plateau at the end of the Columbia Southern Railroad. Freight wagons brought the wool clip from the scattered ranches, and herders drove the lambs to be loaded onto double-decked livestock cars. Sheep ranching reached its highest point when World War I raised the prices for wool and mutton.

The total number of sheep on the central Oregon ranges during the heyday of the sheep ranching period is difficult to estimate. Ranches from much of eastern Oregon drove their flocks to the mountain pastures of the Cascades and the Blue Mountains during the grazing season. California sheepmen shipped their flocks up to Klamath Marsh and the Cascades by rail after the Southern Pacific was completed to Kirk in 1910. Writing in 1906, A.S. Ireland–who was a newly appointed Forest Service official–estimated that 340,000 sheep and 50,000 cattle and horses grazed in the Ochoco and Maury mountains that summer. The open ranges were definitely crowded.

After Congress established the Forest Reserves in the 1890s and the National Forest system in 1905, the forested ranges were closed to new homestead filings, and the Forest Service limited grazing. As a result, fewer sheep were grazed in the mountains on either the public domain or on private homestead tracts. Lower elevation range land was the best alternative, but it also had its share of problems. Large cattle companies like Miller and Lux had gained control of much of the range by buying up water sources and fencing them to exclude smaller operators. The lower elevation range was traditionally cattle country, and sheep and cattle operators did not hold each other in high esteem for a variety of reasons. Cattlemen blamed sheep for overgrazing and for damaging the native grasses. Sheep herders, in turn, blamed the cattlemen for excluding them from the public lands by controlling the water sources.

There were also cultural and ethnic conflicts. The cattle business on the West Coast followed the Mexican model, as it developed on the ranches of California. Western cattle workers called themselves “buckaroos,” a term derived from the Spanish vaquero. In the sheep business, there was a lively ethnic mixture of Irish and Basque. These differing heritages did not always mix well, especially in cow town saloons.

Throughout the American West, periodic conflicts over range lands in the public domain were called “range wars.” The central Oregon range wars started around the turn of the century as more sheep competed with cattle for the lower-elevation grazing. Cattlemen tried to exclude sheep from the public lands by threatening the sheep herders and occasionally shooting the sheep. The Crooked River country was one center of hostilities, and perhaps 10,000 sheep were killed over a period of three years on the ranges east of Prineville. The human toll was slight, however, with only one killing—that of a Silver Lake store keeper—clearly attributed to the conflict.

The livestock business was an important part of central Oregon’s history and provided the first means for Euro-Americans to sustain themselves on the land. However, the stories of the ranching period in central Oregon are not uniformly happy ones. Pioneer rancher John Y. Todd lost most of the 5,000 cattle on his 1880 cattle drive to Cheyenne and was bankrupted. He had to sell his beloved Farewell Bend Ranch to settle his debts. Crook County rancher Bill Brown lost his extensive herds and his 140,000 acres in the 1920s and ended his days in a home for the aged in Salem. The legendary Baldwin Ranch in Jefferson County was sold in 1909, soon after the Forest Service canceled the ranch’s grazing permits. John Newton Williamson, who extolled the virtues of “stock raising country,” was prosecuted by a federal grand jury for land fraud in 1905. On a smaller scale, the Robbins family gave up their homestead on Ochoco Creek and moved into Prineville. One remarkable woman who homesteaded a small ranch alone in the Crooked River Valley finally “starved out” in 1929 and went back east to live with her relatives. Alice Day Pratt wrote in her memoirs: “I gave away my chickens to friends who had helped me in many a tight place. These friends...were to care for...my ponies, which were to run...as long as they lived. I blessed the fact that horses were so over-abundant that they were unencumbered with a mortgage.”

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014