Railroads into Central Oregon

At the turn of the century, when local railroad service had become an established part of the economics and culture of most rural communities in the United States, central Oregon was perhaps the largest geographical area in the United States still without railroads. George Palmer Putnam, scion of a New York publishing family and owner of Bend’s first newspaper, characterized central Oregon in the first decade of the twentieth century as a “railless land...the largest territory in the United States without transportation.” By 1900, railroad builders had approached central Oregon from all points of the compass.

The first serious attempt to reach the area came from the west in the late 1880s. The Oregon Pacific Railway, under the leadership of Thomas Egenton Hogg, built a line east from Corvallis up the North Fork of the Santiam River to Idanha. Hogg then began building east from Idanha across the Cascades, planning to cross Oregon to connect with the transcontinental rail system in Idaho. In 1889, with much of the route graded and some rail in place, Hogg’s creditors forced the Oregon Pacific into receivership and the line was abandoned.

From the north, the Columbia Southern Railroad built a line in 1901 from Biggs on the Union Pacific, seventy miles south across the Deschutes Plateau, to Shaniko. A parallel line, the Great Southern, was built in 1904 from The Dalles, reaching forty miles south into Wasco County. However, neither of these two railroads could negotiate the terrain that led to the Deschutes Valley, so they remained dead-end routes.

As owner of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads, Minnesota financier James J. Hill was well-positioned to build a branch line from his railroad on the Washington side of the Columbia south into central Oregon and then further south into California. This move would create additional traffic for his transcontinental rail system.

Hill had a competitor in central Oregon railroads and property, however, in E.H. Harriman. Harriman controlled the Union Pacific Railway and the Southern Pacific Railway. Harriman and the Southern Pacific investors wanted to reach into central Oregon, but they also wanted to control the region by connecting it to their other railroads—the Southern Pacific line in the Willamette Valley and the Union Pacific line on the Oregon side of the Columbia River. This triple connection would dominate the central Oregon market and assure that all cargoes originating in central Oregon would enter the interstate market on a Harriman railroad. To this end, Harriman incorporated the Des Chutes Railway to build up the Deschutes River to Bend.

It was no easy task to build a railroad up the Deschutes Canyon. The gradient was gentle enough, but the rocky passage through the canyon required careful engineering and several substantial bridges. In the 1854–1855 survey of Pacific Coast railroad routes, Henry Larcom Abbot found central Oregon to be an inhospitable region for the railroad, finding it “separated from the rest of the world by almost impassible barriers.” According to Larcom, “nature seems to have guaranteed it forever to the wandering savage and the lonely seeker after the wild and sublime.”

W.F. Nelson, a Seattle railroad builder, incorporated the Oregon Trunk Railway and planned a route up the Deschutes in 1906. James J. Hill bought the Oregon Trunk from Nelson’s successors in 1909 and assigned his best civil engineer, John F. Stevens, to design a route to Bend. By the mid-summer of 1909, crews from Hill’s Oregon Trunk and E.H. Harriman’s Des Chutes Railroad began the work of building two parallel railroads up the Deschutes Canyon on opposite sides of the river. The Hill forces were working on the west bank of the river, and the Harriman forces were grading on the east bank, with advance parties from both lines claiming strategic points in the canyon. Materials and supplies for the two railroads swamped the local wagon roads, and the Columbia Southern and Great Southern railroads enjoyed their last profitable months. In the rival construction camps, feelings ran high. Dynamiting, sabotage, and brawls punctuated the long summer and fall. George Palmer Putnam covered the scene for the newspaper wire services: “At one point the Hill forces established a camp reached only by a trail winding down from above, its only access through a ranch. Forthwith the Harriman people bought the ranch, and “no trespassing” signs, backed by the armed sons of Italy, cut off the communications of the enemy below.”

By the end of 1909, the silliness of the “Deschutes Canyon War” was apparent to both sides. E. H. Harriman had died that autumn, subsequently James J. Hill and Robert S. Lovett, Harriman’s successor, worked out an agreement for joint operation by May 1910. Both railroads would use the Oregon Trunk line from North Junction to South Junction (10.4 miles) and from Metolius to Bend (42.6 miles). Both railroads would also use the twenty-four miles of Des Chutes Railroad track from South Junction to Metolius. With the drama gone, the railroad building proceeded smoothly, with passenger service completed to Bend on November 1, 1911.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

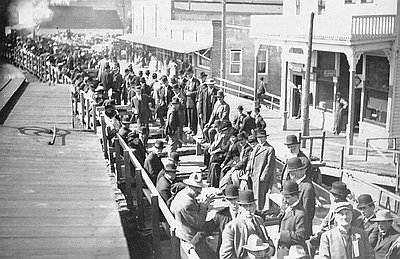

Wool Buyers at Shaniko

This photograph features wool buyers at Shaniko in eastern Wasco County. In 1910, the approximate date of this photograph, Shaniko was a major transportation hub linking central and …

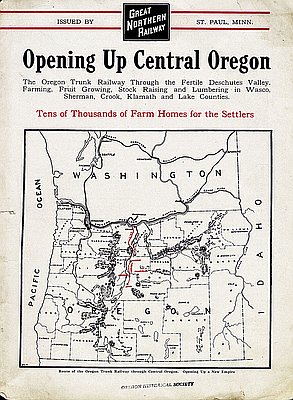

Brochure, Opening Up Central Oregon

In 1911, laborers completed the Oregon Trunk Railroad from the Columbia River, near Celilo Village, to Bend, giving large timber companies a way to export timber from the …