Pre-Industrial Communities

Prineville holds the distinction of being the region’s first town, founded by Barney and Elizabeth Prine in 1868. The Prines settled on the banks of the Crooked River where they established a road ranch. Like other examples of these frontier institutions, the Prines’ place provided services including a store, a blacksmith shop, and perhaps some overnight accommodations. The Prines sold out to Monroe Hodges and his family. Hodges expanded the business to include a proper hotel, a meat market, a livery stable, and facilities for horse trading, horse racing, and other equine activities. The Crooked River country was open range in the 1870s, and Prine, as the first Prineville post office was named in 1871, was a central place for the rapidly settling valley.

As Prineville and the surrounding Crooked River country settled up in the late 1870s, the political situation began to annoy the central Oregonians. The county seat of Wasco County was The Dalles, located 200 miles to the north. Services and representation for central Oregon were minimal. The movement to secede from Wasco County began in the late 1870s and led Prineville resident and Wasco County Representative Frank Nichols to introduce a bill to form Crook County in 1882.

The same year, or possibly the year before, saw the formation of a local vigilance committee, the famous Crook County Vigilantes. The vigilantes ostensibly formed to maintain law and order in Crook County in the first years of its independence from Wasco County. During 1882 and 1883, the vigilantes were active in the new county, but “law and order” did not seem to figure into their agenda. A rancher named Lucius Langdon shot two of his neighbors in March 1882. Community members took sides in the dispute, leading to a series of shootings and lynchings that finally left nine men dead. Til Glaze’s saloon in Prineville was the epicenter of vigilante activity, but the three other saloons in Prineville had their share of excitement as well.

The personalities and episodes of the vigilante period have been mulled over in dozens of conflicting accounts. But all agree that the violence ended after the first regular election was held in June 1884. Opponents of the vigilantes won office, and rancher Jim Blakely led his anti-vigilante group, the Citizens’ Protective Union in a show of armed force on Prineville’s main street. The conflict then became a war of words, with both sides publishing accounts justifying their actions. The vigilantes’ side was represented by William Thompson in his Reminiscences of a Pioneer and the anti-vigilantes’ side was represented by James Blakely, who outlived all the others and consequently had the last word.

In the ensuing years of the 1880s, Prineville established itself as a cow-town in the best sense of that term, providing services for the ranches of the Crooked River Valley and points east. When the Oregon Trunk Railroad came through central Oregon in 1910, it followed a north-south course from Madras to Redmond, and consequently missed Prineville by twenty miles. For many frontier towns, this would have been a death sentence, since communities on the railroad had enormous advantages. Within a few years, however, the citizens of Prineville had built their own railroad, linking the town to the Oregon Trunk and the transcontinental system. This municipal railroad languished for a few years, then proved its value as the community industrialized in the late 1930s.

Prineville in the late 1930s was the scene of a burst of enterprise that established several lumber companies and one of Oregon’s legendary fortunes. All the ingredients were in place before the Depression. Excellent timber was available in the Ochoco National Forest and on extensive private holdings. The city of Prineville had built a railroad to connect with the transcontinental rail network. However, there was no industrial-scale lumber production in Prineville until the late 1930s.

The timber industry arrived in Prineville over a period of three years. In 1935, W.L. Forsythe and Howard Crawford, both timber operators from Redmond, formed the first of the 1930s Prineville companies, Pine Products, and began cutting lumber. Soon after, in 1937, the Alexander interests of Wassau, Wisconsin, created the Alexander-Yawkey Lumber Company and built a mill near Prineville. Partners in this mill included members of the Daggett family from Klamath Falls, owners of the Ewauna Box Company.

In 1938, John Shelk, associated with the Booth-Kelly Lumber Company of Eugene, built a mill for the Ochoco Lumber Company to process the cut from their private holdings and from public timber guaranteed by a contract with the Ochoco National Forest. Other Crook County mills started in the late 1930s and early 1940s included Consolidated Pine, Kelly Lumber, Midstate Lumber, Paulina Lumber, and other smaller mills.

Redmond was as closely allied to irrigated farming as Prineville was to ranching. The founders, Frank and Josephine Redmond, filed a homestead claim and pitched a tent next to the Deschutes Irrigation and Power Company’s main canal in 1904. Adjacent to their claim was the projected route of the railroad. Water from the Deschutes reached the site in 1906, and the community that had grown up around the Redmonds’ place organized the first Redmond Potato Show that year. Although the potato business was just getting started, the show celebrated local potatoes, promoted as the “Deschutes Netted Gems.” The annual Redmond Potato Show became the Deschutes County Fair after Deschutes County was formed from the southern and eastern parts of Crook County in 1916.

Redmond prospered as a market town for the farms and ranches in what became the northern half of Deschutes County. During the middle and late 1930s, Redmond industrialized as entrepreneurs from outside the area built saw mills to cut logs into lumber and planing mills to finish the lumber. One of central Oregon’s first molding plants, Ponderosa Moldings, began production in 1939. Molding plants made pine lumber into molding, casing, and cut stock for various applications. During World War II, Redmond’s municipal airport, Roberts Field, became a training base for Army Air Corps bombers and fighters. After the war, it served as a Forest Service smoke-jumper base and eventually as a regional airport.

Madras began as a town plat filed in 1902 by homesteader John Palmehn. Palmehn had come to the area in 1893. The town was incorporated in 1910, coinciding with construction of the Oregon Trunk Railway. According to legend, the town name was supposed to have been “Palmehn” but in the application process was misspelled as “Palmain.” Supposedly this was rejected by the Post Office as being too similar to “Palmer,” a name already chosen by another town. According to one version of the story, someone noticed a bolt of Madras pattern cloth and suggested that the town be called “Madras.” Others contend that the name was chosen because of the early settlers’ spiritual affinity with the city in India.

Madras and the surrounding area seceded from Crook County in 1914 to form Jefferson County. Culver became the first county seat. In a subsequent election, Madras was named county seat. Litigation followed the election, as the people of Culver were reluctant to surrender their position of importance in the county. A self-appointed group of citizens from Madras descended on the Culver courthouse, seizing public records, furniture, and other artifacts of county government. As Madras’s first mayor, Howard Turner, recounts the story, “some of the boys were rather jubilant, having imbibed a little too much and were in a belligerent mood.” The county attorney threatened to prosecute the mob, but the county sheriff sensibly barricaded himself in his office until the Madras boys carried off the records and the equipment of county government.

During the 1930s, Madras made a brief appearance in print. Erskine Caldwell, novelist of the rural South, visited the town, and in Some American People wrote about Madras’s progress through the Great Depression: “At ten o’clock in the morning all the stores in the town of Madras that were going to open had opened. Half of them have been vacant and boarded shut for nearly a year; the hardware merchant and the dry-goods merchant couldn’t get by on just taking in each other’s washing.”

Caldwell blamed Madras’s poor economy on dry farming, which he felt was inappropriate in the area. In fact, Madras was located in one of the most successful dry-farming areas in central Oregon. Dry farming declined, however, with the completion of the North Unit canal in 1946. Water from the Deschutes irrigated much of the Jefferson County farm land, including the former dry farming areas on Agency Plains. The dominant crops shifted from wheat to potatoes, clover seed, mint, and later to grass seed, garlic, and dill. These specialized products were very profitable, and they cemented Madras’s position as an agricultural market town.

Before the railroad, the sawmills, and the influx of industrial workers, central Oregon homesteaders were isolated from each other and from the outside world. Most settlers “made their own entertainment” with folk arts including music, letter-writing, and story-telling. Letters from central Oregon correspondents like the Robbins family and Alberta McCabe are remarkable for their ability to present the drama of the frontier and at the same time show us the ordinary details of domestic life. Sick children, balky animals, household budgets, and social occasions have the same importance in the letters as Paiute Indian attacks, stampedes, and the occasional desperado. The letters also show us family correspondence conducted at the level of craft if not quite art. Alberta McCabe’s witty and articulate letters were meant to amuse her father in Detroit, and they surely amused her as well. The pleasure she took in her writing comes through in her ironic narrative voice: “We are all well except when I forget to boil this pure mountain snow water, as the natives feelingly refer to it, [then] we all have dysentery.”

Another widely-practiced home-made form of entertainment was story telling. The story telling tradition at Warm Springs remained strong. Stories of Coyote and other animal characters date back to the earliest times of the Sahaptin and Wasco people. Many of these oral tales are recorded and re-told in Jarold Ramsey’s Coyote Was Going There. Writing these stories changes some of their characteristics, of course, and compromises the spontaneous nature of traditional story-telling, but it is important to record the tales before they are lost.

Reub Long, a homesteader and horse rancher from the Ft. Rock Valley is central Oregon’s best example of a Euro-American story teller. Reub’s stories and anecdotes have been recorded in several sources. Included in the repertoire of any self-respecting central Oregon story teller would be several stories about the eccentricities of Bill Brown, a good rendition of the Lost Meek Party and Blue Bucket Gold, and—for telling beside a campfire—the story of Billy Quinn’s murder high in the Cascades.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

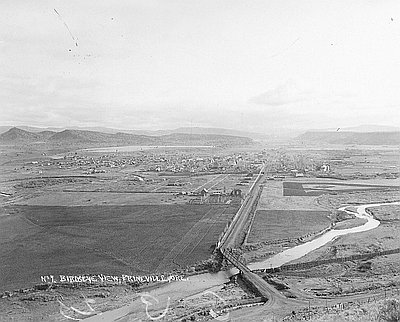

Bird’s-eye View of Prineville, c. 1915

This bird’s-eye view of Prineville, Oregon was taken by Charles Wesley Andrews (1875–1950) around 1915. The photograph looks east down Main Street. Ochoco Creek is visible passing through …

Farmer Receives Deschutes Irrigation Project Water

This photograph shows George Rodman spreading irrigation water over his farmland near Culver on May 18, 1946. Rodman was the first farmer to receive water from the Deschutes Irrigation …

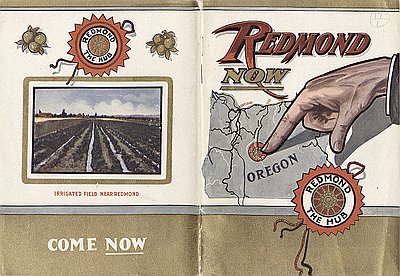

Redmond Now, Promotional Pamphlet

This promotional pamphlet of Redmond, Oregon was co-published by Southern Pacific and the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company in 1910. The railroad companies hoped to attract settlers to …