New Times, New People

Industry provided the elements that brought new settlements to central Oregon: economic growth, communication with the outside world, increased population, and increased community resources. As we have seen, the isolation and difficult climate of central Oregon made agriculture a chancy business. The first Euro-American settlers were unable to meet the Jeffersonian ideal of self-sufficient farming. When the Native Americans were moved from their ancient home on the Columbia and Deschutes to the Warm Springs Valley, the federal government encouraged them to take up farming and ranching. Although they did pursue these activities, they met with only modest success and relied on fishing, hunting, and gathering to supplement the meager output of their agriculture.

To survive, both the Native American and Euro-American settlers in central Oregon needed a cash income. Their farms did not produce large-enough surpluses and there was little opportunity to sell agricultural products because, until 1910, there was no transportation system to get the goods to market. Livestock ranching was less dependent on transportation than farming, but the capital and labor requirements for ranching were beyond the means of many immigrants.

As the regional industrial base grew, it brought with it a new population. Between 1910 and 1920, the population of Bend increased from less than 500 to more than 5,000. Scandinavian and Slavic emigrants came to work in the mills and forests. Italians and Greeks came to work on the railroads. Employment in the mills meant additional income to support marginal farms and ranches. Mill work and union membership also brought medical and disability benefits and pension plans that were not available on the farms and ranches. The forty-eight-hour work week in the mills was demanding, but it allowed for far more leisure than the sixty-hour work week required of successful farmers or ranchers. Leisure pursuits such as mountaineering and other outdoor sports took root in central Oregon during the industrial period, and the businesses based on recreation served the region well in the post-industrial years.

Nearly every successful community in central Oregon had railroad service and a lumber mill. Towns on the Oregon Trunk line included Maupin, Madras, Redmond, Bend, and La Pine. Prineville built its own municipal railroad when the Oregon Trunk passed it by. The Gilchrist Lumber Company mill was served by a private railroad, the Klamath Northern. The Warm Springs Tribal mill trucked its lumber a few miles from the mill in Warm Springs to the railroad at Madras. Sisters did not have regular rail service, although the Brooks-Scanlon logging railroad ran through Sisters from the late 1930s until the mid-1950s.

All of the larger central Oregon towns were to some degree “mill towns.” The first and largest of the industrial towns was Bend, with the Brooks-Scanlon and Shevlin-Hixon super-mills beginning business in 1915. During the 1920s, other smaller mills flourished throughout the area. After the national depression of the 1930s, the industry recovered and built a second generation of mills in Warm Springs, Maupin, Sisters, Redmond, Prineville, and Gilchrist. Then, as the industrial period waned through the 1960s and 1970s, secondary production mills made windows, doors, and millwork in Madras, Bend, Redmond, and Prineville.

As early as 1912, national lumber publications had recognized that central Oregon would be play an important role in the future of the American pine industry. During the next few decades, the industry press, as well as regional newspapers in Oregon and Washington covered the central Oregon scene. The American Lumberman and the Timberman ran frequent pieces about the industry in central Oregon, and the Timberman had a regular column devoted to Bend. The technology and the marketing practices developed in the pine mills in south-central Oregon and northern California were a model for the pine industry and were imitated by firms in other parts of the country. Labor relations and working conditions in the pine belt were also a national model, especially when compared to the grim conditions prevailing in the southern pine mills or the Great Lakes logging camps.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

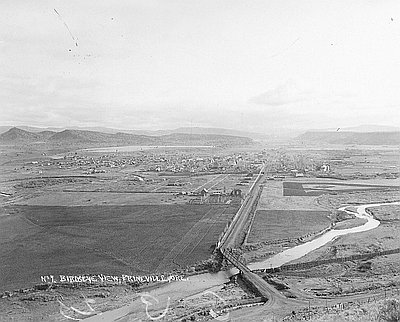

Bird’s-eye View of Prineville, c. 1915

This bird’s-eye view of Prineville, Oregon was taken by Charles Wesley Andrews (1875–1950) around 1915. The photograph looks east down Main Street. Ochoco Creek is visible passing through …

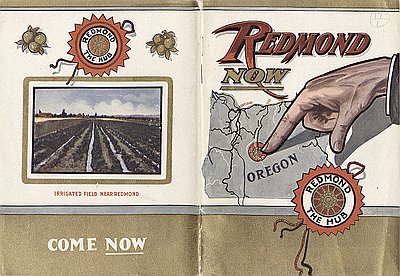

Redmond Now, Promotional Pamphlet

This promotional pamphlet of Redmond, Oregon was co-published by Southern Pacific and the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company in 1910. The railroad companies hoped to attract settlers to …

Shevlin-Hixon and Brooks-Scanlon Mills, Bend

This photo shows Bend, Oregon’s two largest lumber mills. The Brooks-Scanlon mill is on the far side of the Deschutes River, in the background of the photo; the …