Lumber Follows the Rails

In his colorful account of the American lumber industry, Oregon writer Stewart Holbrook commemorated the “pure logger strain” of American worker who “came into being on the grim wooded shores of Maine three hundred years ago...rose to fullest stature in the Lake States of the nineteenth century, and is now [in 1938] passing out of existence on the West Coast and in the Pacific Northwest.”

The progress of the national lumber industry through the nineteenth century was certainly colorful, but it also brought the worst excesses of laissez faire capitalism. Nearly a decade after the century’s end, in 1909, U.S. lumber production reached a crescendo of 44 billion board feet, a figure that was not exceeded until the late 1980s. In 1910, Congress asked the Bureau of Corporations to investigate the lumber industry and to report on its current state. The resulting publication in 1913 and 1914 of the Bureau’s report—simply titled The Lumber Industry—provided the details of a century of financial opportunism. Not surprisingly, the report identified several firms with holdings in central Oregon as perpetrators of land fraud and predatory business practices.

Herbert Knox Smith, Commissioner of Corporations, wrote in his Letter of Submittal that the Bureau’s investigation confirmed “the concentration of...our standing timber in a...few enormous holdings...vast speculative purchase of timberland...[and] an enormous increase in the value of this diminishing natural resource.” Lumbermen had plundered the public domain for decades, he argued, by accumulating public lands into private holdings and monopolizing the supply of timber. Smith blamed public lands policies for allowing this travesty and urged that they be revised.

The ponderosa pine forests of central Oregon, including portions of Deschutes, Klamath, Lake, Crook, and Jefferson counties attracted the attention of the pine lumber producers in the Great Lake states of Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin before the turn of the century. Many of these firms began acquiring timber lands in the western “pine states” as early as 1895, when the growing network of timber reserves threatened to place public lands beyond the reach of lumber companies.

In January 1910, the lumber industry journal, the Timberman, ran a feature on “The Invasion of Central Oregon by Hill and Harriman Lines.” According to the author of the article, central Oregon offered “the greatest body of standing pine timber now existing in America” and new railroads were making it accessible to lumber companies. The reporter estimated that federal forest lands in central Oregon held 27.6 billion board feet of pine. When the amount of merchantable timber on the reservations was added to the central Oregon total for public lands, the figure rose to more than 35 billion board feet. Private holdings north of the Klamath Divide were estimated at 9 billion board feet, and private timber south of the Klamath Divide was estimated at a similar figure. The total for the pine belt of central Oregon, then, was approximately 55 billion board feet of ponderosa timber still “on the stump.”

In 1910, the volume of timber on the Warm Springs and Klamath reservations was still unknown because the Indian Service had not yet made data from preliminary timber cruises public. Prior to 1910, the policy of the Department of the Interior’s Indian Service forbade the sale of green timber on Indian reservations throughout the United States. Fire-killed or beetle-infested trees could be sold, but these had little value at the time. After 1910, when the Indian Service began selling timber from reservation lands, forests on the Klamath Reservation attracted numerous bidders, while timber on the Warm Springs Reservation did not. One sale on the lower Metolius was contracted, but the timber was not logged. Commenting on early Indian Service sales, Chief Nelson Wallulatum of the Wascos remarked in 1982, “During the late 1920s and early 1930s...we had very little communication with the outside world...and, of course, there was no demand for timber at the time.”© Ward Tonsfeldt & Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

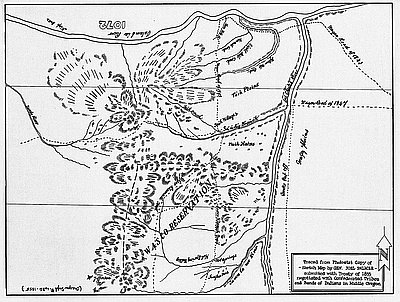

Wasco (Warm Springs) Reservation Map, 1855

From 1854 to 1855, Joel Palmer, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, negotiated nine treaties between Pacific Northwest Indians and the U.S. government. Many Indians agreed to …

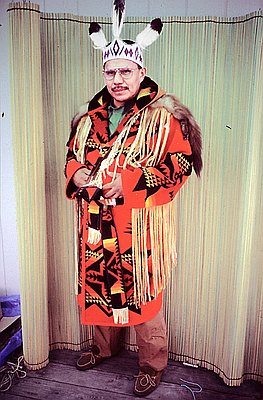

Tule Mats

This photograph of Taw Li Winch (“tule man” in English), posing in front of a large tule mat, was taken in 1995 during his participation in the Traditional Arts …

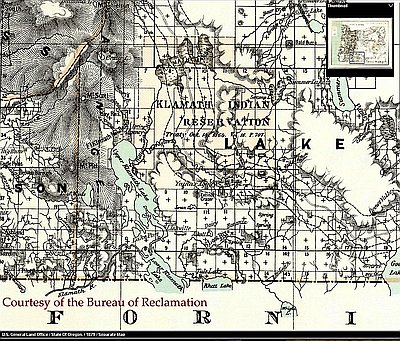

Klamath Indian Reservation

When white explorers entered the Klamath Basin in the 1820s, the Klamath Indians occupied the Upper Klamath Lake area, which included Klamath Marsh and the Sprague and Williamson …