Uneasy Settlement

With a sunny climate, a resort atmosphere, and skiing, golfing, hiking, and camping, central Oregon is a center of outdoor recreation. A population boom, beginning in the 1980s, made Bend the fasted-growing city in the state by 2006. Newcomers arriving from all parts of the United States. Many of these people are “urban refugees”—retirees seeking a quiet life in a secluded corner of the West. Beneath the ski resort and boutique surface, however, central Oregon has a vital regional history.

In some respects central Oregon’s past reflects broad national and regional patterns. This is true of such events as the relocation of Native American tribes from their homes on the Columbia River to the Warm Springs Reservation in the 1850s, the industrial depredations on the vast pine forests, and the recent demographic shift from a largely Native American and Euro-American population to one that is more ethnically diverse.

In other respects, central Oregon’s past is unique. Unlike other parts of the Pacific Northwest, central Oregon did not welcome settlement. The aridity and the short growing season kept pre-historic populations low and frustrated Euro-Americans who tried to farm the thin volcanic soil. For the tribes relocated to the Warm Springs Reservation, farming and ranching, as advocated by the Indian Service, were especially difficult. The history of central Oregon is a history of adaptation and compromise, as people found ways to live in an area that offered great promise but slender resources.

Although we do not know when the term “central Oregon” was first used, it must have been familiar by 1905, when the first account of the region’s history—An Illustrated History of Central Oregon—appeared in print. A.B. Shaver and the other authors of the Illustrated History defined “central Oregon” by taking a broad north-south slice out of the state’s middle. Beginning at the Columbia River and moving south, they included Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam, Wheeler, old Crook County, Lake, and Klamath counties. This was expedient, but a little over-inclusive. Klamath and Lake counties have their own history, as do the counties on the Columbia Plateau. As the term is most commonly used now, central Oregon refers to the center of Shaver’s central Oregon–the 10,000 square miles drained by the Deschutes River.

The great irony of the 1905 Illustrated History of Central Oregon is that the 1,097-page volume celebrated the history of Euro-Americans in a region that did not have much Euro-American history at the time. White settlement had begun a scant fifty years before 1905, and the cultural elements that were to pull the scattered settlements together were only beginning to emerge. In 1905, the rest of America was greeting the twentieth century. Portland was celebrating the Columbia Exposition and the Lewis and Clark centennial. Central Oregon, however, was a little behind the times.

The upper Deschutes country and the surrounding hills held a few hundred settlers who had sorted themselves into loose communities adjacent to water in 1905. Members of the Warm Springs tribes still traveled through the country on horseback, following their traditional subsistence rounds. The dominant activity for the settlers was stock-raising. Sheep, cows, and horses outnumbered people by several orders of magnitude. Farming was making a debut in 1905, but the irrigation systems that were to make farming viable were still in their infancy. Since there were no rail lines in central Oregon, people relied on horses or simply walked, and goods moved by freight teams.

Electricity came to Prineville, then the largest town of central Oregon, in 1905. The generator was hauled by team 175 miles from the end of the nearest railroad. The City of Bend was incorporated in 1905, but as recently as 1904 Frank and Josephine Redmond were still living in a tent near the townsite that would soon bear their name. The worst of the range wars were pretty well over by 1905, but in 1904 cattlemen east of Prineville shot 2,400 sheep. Telephone service connected Prineville, Bend, and Madras with the outside world in 1904. Hugh O’Kane, gambler and organizer of crude frontier entertainments, had just opened the Bend Hotel in 1905. Dr. Urling Coe, one of Bend’s first physicians, describes a central Oregon street scene at the time:

Freighters, stockmen, buckaroos, sheep herders, timber cruisers, gamblers, and transients of all kinds who had been attracted to the town by the boom thronged the bars or played at the gambling games, and the stores were doing a rushing business. The stores remained open in the evenings and the saloons remained open all night and all day Sunday, and many of the laborers from the construction camps spent the weekends in the town, drinking, gambling, carousing, and fighting.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

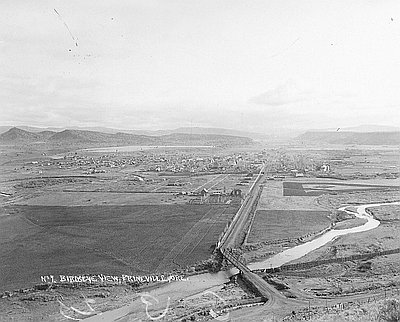

Bird’s-eye View of Prineville, c. 1915

This bird’s-eye view of Prineville, Oregon was taken by Charles Wesley Andrews (1875–1950) around 1915. The photograph looks east down Main Street. Ochoco Creek is visible passing through …

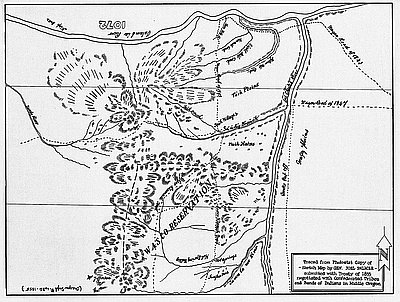

Wasco (Warm Springs) Reservation Map, 1855

From 1854 to 1855, Joel Palmer, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, negotiated nine treaties between Pacific Northwest Indians and the U.S. government. Many Indians agreed to …

Redmond Now, Promotional Pamphlet

This promotional pamphlet of Redmond, Oregon was co-published by Southern Pacific and the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company in 1910. The railroad companies hoped to attract settlers to …