Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon

In June 1855, Joel Palmer, Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, met at The Dalles with representatives of the various Upper Chinookan and Sahaptin peoples of the mid-Columbia River in order to negotiate a treaty between them and the Unites States. These groups included the Tygh, Wyam, Tenino, and Dock-Spus bands of the Walla Walla, and the Dog River, Dalles, and Ki-Gal-Twal-La bands of the Wasco. In the final agreement, titled the Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon, these groups ceded to the U.S. government approximately 10 million acres of land south the Columbia River between the Cascade and Blue Mountain ranges. The groups that became the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation also reserved 578,000 acres south of the Columbia on the Deschutes, Warm Springs, and Metolius rivers for their exclusive use. The treaty also preserved the groups’ traditional practices of traveling to various off-reservation sites for fishing, hunting, and gathering.

The treaty proposed by Palmer was advantageous to the U.S. government because it largely removed the Upper Chinookan and Sahaptin peoples from the Columbia River corridor. The river was destined to become a major east-west route connecting the Pacific slope and the western valleys to the inland regions of the Pacific Northwest. The land that the Warm Springs tribes reserved for their own use was a remote corner of their territory. Mark, a Wasco elder, is quoted as telling Palmer: “The place you have mentioned, I have not seen. There [are] no Indians or Whites there yet, and that is the reason I say I know nothing about that country. If there were Whites and Indians there then I would think it was a good country.” The tribal members themselves did not perceive the reserved land as “real estate”—as a commodity to be bought and sold.

After the treaty was ratified in 1859, the tribes moved onto the reservation, but continued to fish at Celilo and travel throughout the upper Deschutes country for hunting, gathering, trading, and visiting distant friends and relations. In September 1912, Alberta McCabe described groups from Warm Springs near Sisters: “The Indians are thick everywhere you go. Parties of them camp by our ditch here nearly every night. Some of them look very prosperous and all are gaudily dressed. They have so many horses, ten or twelve extra ones with each crowd.”

In the years after the signing of the 1855 treaty, there were several infringements on the original understanding that constituted bad faith on the part of the federal government. The first of these was the so-called Huntington Treaty of 1865, which ostensibly limited tribal members’ freedom of movement off the Warm Springs Reservation. As the 1969 Belloni decision and subsequent court decisions have held, the terms of the 1865 treaty were not legal and they were not honored in practice. The second and more serious was the Dawes Act, passed by Congress in 1887. This legislation sought to commodify the Indian reservations in the United States, transforming the land into ordinary real estate by allotting individuals separate tracts. After twenty-five years of residence, the allottee would receive title in fee simple and could sell the land. The Dawes Act devastated the smaller reservations in Oregon, including the Grande Ronde and Siletz reservations on the coast. The larger reservations fared better. On the Warm Springs and Klamath reservations, the necessary government surveys of the land took more than fifteen years to complete. Because the number of potential allotments far exceeded the number of tribal members, relatively little land went into allotments—only 20 percent on Warm Springs—and very few allotments reached title status. As a consequence, few allotments were ever sold. The Wheeler-Howard Act repealed the Dawes Act in 1934.

After the Upper Chinookan and Sahaptin peoples of the mid-Columbia were relocated to the Warm Springs Reservation, Paulina, the well-known Northern Paiute leader, became concerned about encroachments on traditional Paiute territory. He led his band in raids against the Warm Springs tribes, white settlers in the Crooked River valley, and miners on the roads to the John Day country. By the mid-1860s, Paulina had a formidable reputation and few friends on or off the reservation. Volunteers from Warm Springs enlisted in the U.S. Army to form the elite Warm Springs Scouts. They joined with regular army units in pursuing Paulina around the middle Deschutes country from 1864 until 1867. That year, Paulina was shot by a rancher in the Trout Creek country. Later, under the leadership of “Daring” Donald McKay, the Warm Spring Scouts distinguished themselves fighting in the Modoc War in southern Oregon and northern California.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

Chief Paulina

This photograph of Chief Paulina was likely taken in 1865 when Paulina was living on the Klamath Reservation. Paulina was a well-known war leader associated with the Hunipuitöka, …

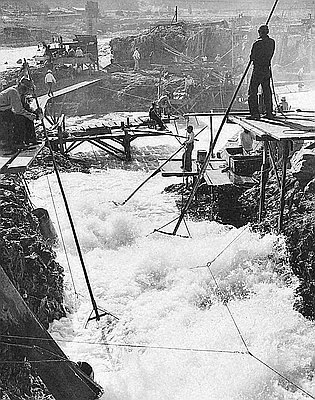

Indians Fish at Celilo Falls

Celilo Falls was an important center for native trade, culture, and ceremony. For at least 11,000 years, tribes throughout the region, and from as far away as the …

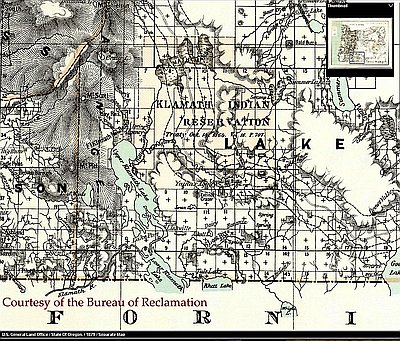

Klamath Indian Reservation

When white explorers entered the Klamath Basin in the 1820s, the Klamath Indians occupied the Upper Klamath Lake area, which included Klamath Marsh and the Sprague and Williamson …