World War II

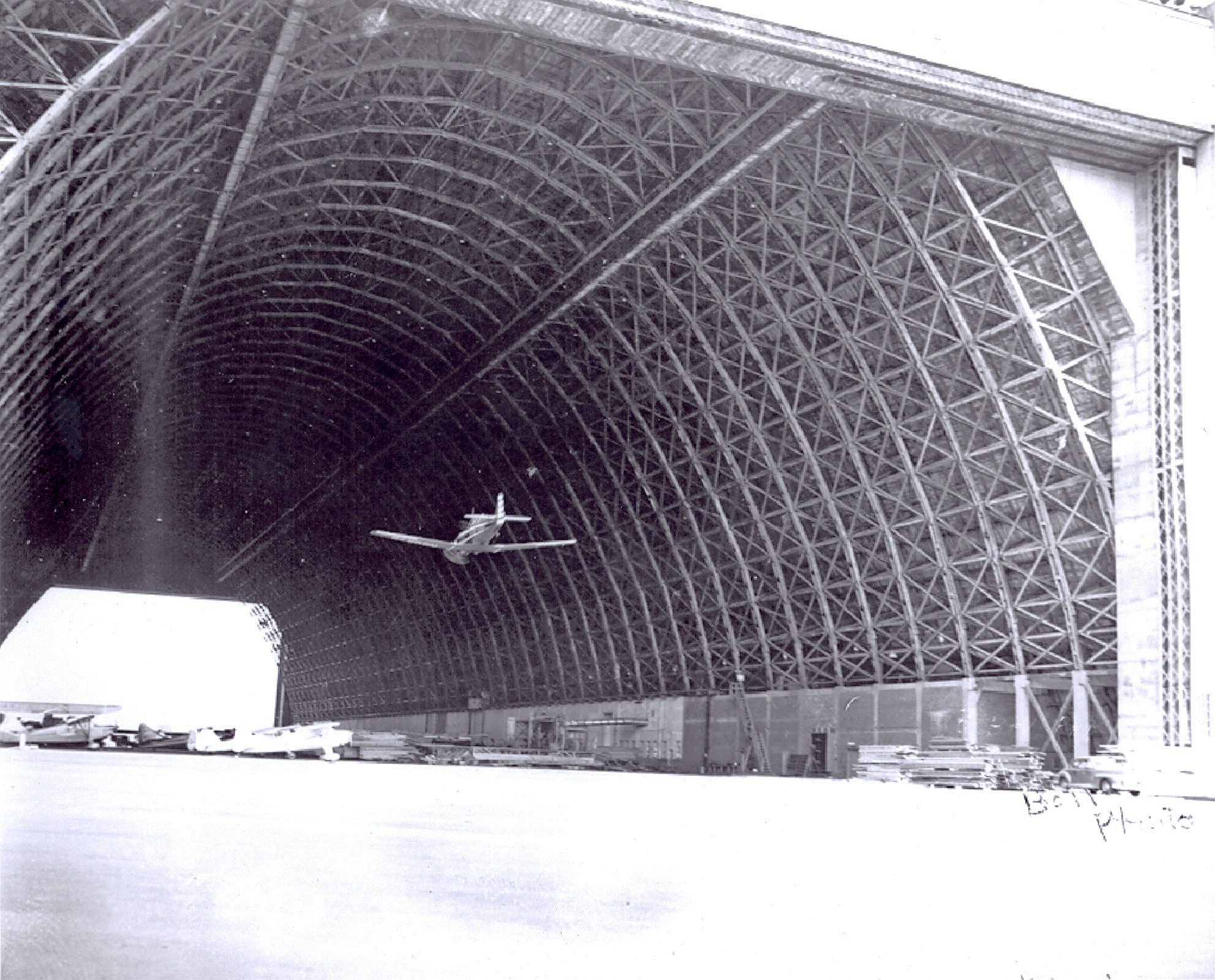

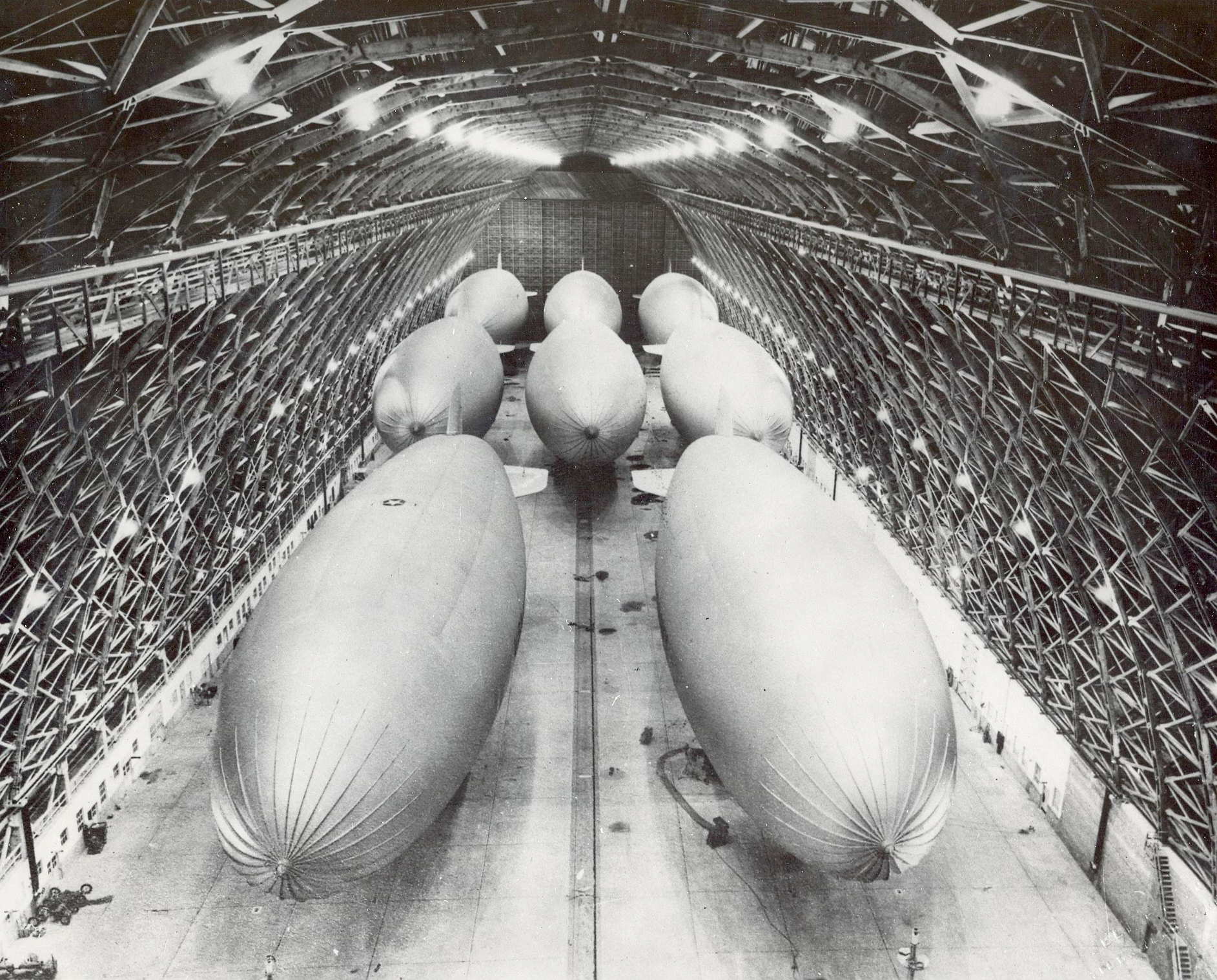

Eight K-class airships of Squadron ZP-33 in hangar at Naval Air Station Tillamook

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the war in the Pacific was even near at hand for those living on the West Coast. A wartime mentality set in immediately, as coastal residents were commanded to black out their homes at night by covering windows with shades and blankets. Block wardens patrolled neighborhoods, looking for telltale lights and reprimanding offenders. Volunteers watched for airplanes, soldiers and the Coast Guard patrolled offshore waters, and coast watchers and their dogs walked the beaches. Men, women, and children collected scrap metal and paper for the war effort, and men and women in Lincoln County staffed beach lookout towers twenty-four hours a day. Other communities, working with the Army Air Corps’ Second Interceptor Command, built strategic lookouts along the coast, including one in Taft Heights. Among the defense groups formed during the war was the Oregon Women’s Ambulance Corps, initially organized by women in Oceanlake.

The U.S. Naval Air Station near Tillamook was commissioned almost exactly a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It consisted of two of the largest wood-frame buildings ever built in the area, perhaps the largest in the world—hangars for blimps that patrolled the coast looking for enemy ships and submarines.

There was reason for vigilance. On the night of June 21, 1942, a Japanese submarine fired seventeen shells at Fort Stevens, near Astoria. Most of the shells landed in a swampy area at the edge of the fort, and some exploded on the beach or buried themselves in the sand. The shelling caused no damage, and soldiers were ordered not to return fire. Because of the incident, Fort Stevens has the distinction of being the only military installation in the continental United States to be fired on since the War of 1812.

Later that year, on September 9, a small plane carrying a pilot and copilot was catapulted off the deck of a Japanese submarine near Brookings on the south coast. The men flew over the Siskiyou National Forest and dropped incendiary bombs, but they did not succeed in igniting anything. The devices were a Japanese strategy to set forest fires along the West Coast to divert American attention from the war. In May 1945, a Japanese incendiary balloon exploded at a church picnic near the eastern Oregon town of Bly, killing the minister’s pregnant wife and five children. The balloon had reportedly floated 6,200 miles on air currents before coming to earth near the Klamath County town. Oregon was the only American state to suffer civilian casualties during World War II, and one of the very few states to be both shelled and bombed by a wartime enemy.

Those who objected to war on principle also had a base on the Oregon Coast. Civilian Public Service Camp No. 56 at Waldport, operated by the Mennonite Church, was one of about 150 such camps established during World War II where conscientious objectors could work off their service obligation. Writers and poets at Camp No. 56 formed a “fine arts group” and established the Untide Press, which issued two periodicals and published volumes of poetry.

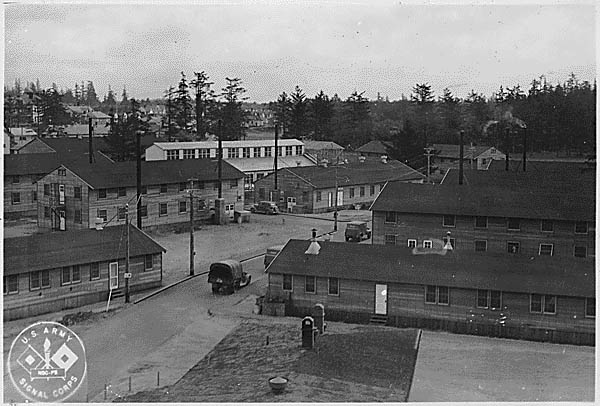

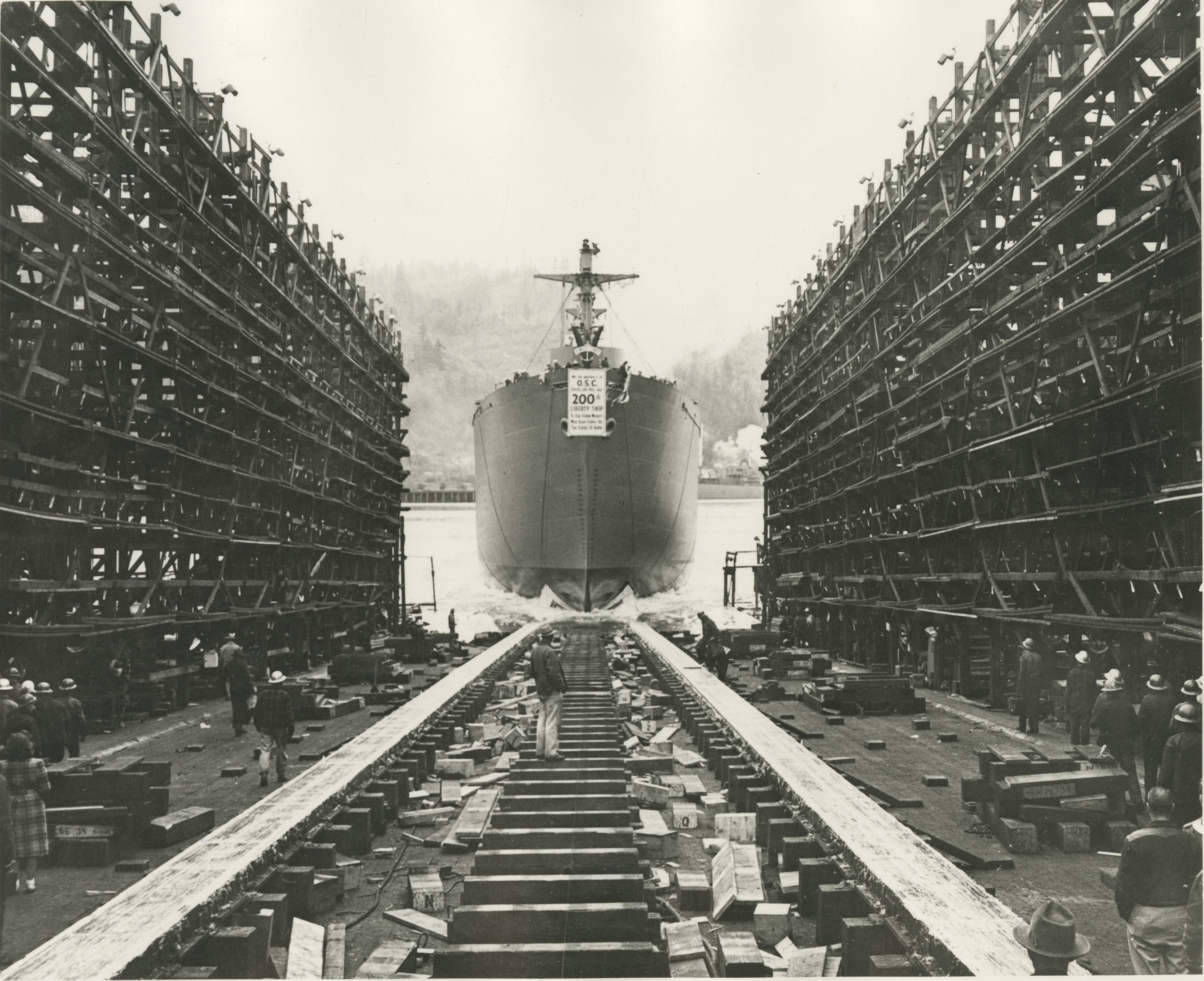

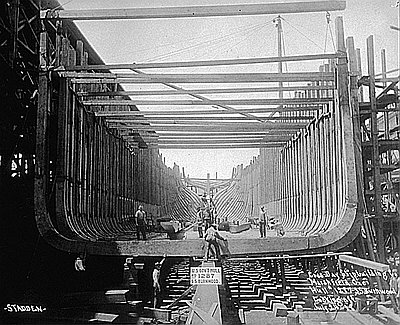

In general, war brought good economic times to Oregon. Jobs were plentiful and workers were scarce, and coastal communities enjoyed full employment and regular paychecks. The war effort needed military bases, barracks, officer quarters, civilian housing, airplane hangars, PT boats, minesweepers, boxes, crates, pallets, ship decking, and railroad ties. All of these required lumber and plywood, boosting demand at a time when many men of working age had left their jobs in the mills and the woods to fight in the war.

By the spring of 1942, labor was in severely short supply. War work tended to pay better than woods work, and so some workers left the coast for jobs in defense plants, including the Kaiser shipyards in Portland that employed an estimated one hundred thousand workers by 1943. The federal government tried its best to lure experienced loggers back to the woods. According to historian William Robbins, “On one occasion, more than 300 loggers left their jobs in the Kaiser shipyards in Portland to go back to camps in the Columbia River country. The men reportedly left the shipyards at the request of War Manpower Commission chairman Paul McNutt, who declared that logging was the ‘Number 1 manpower problem in the West.’” There is no evidence, Robbins writes, that shipyard workers returned in large numbers until the war ended.

The wartime labor shortage brought significant numbers of women into the labor force, working on factory assembly lines, typing and filing in offices, driving buses, clerking in shops, and operating telephone switchboards. In coastal timber towns that were suffering from manpower shortages, women were accepted, if not always welcomed, into all-male domains such as millwork and logging. The workforce at the Evans Products battery-separator plant in Coos Bay was two-thirds female during the war years. Because of union pressure, the women earned the same pay as men doing equivalent jobs.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.