The Great Depression

The lumber industry, buoyed by heavy orders and high prices during World War I, weathered the postwar economic decline, and remained the region’s predominant industry. By 1929, Northwest sawmills were cutting 11.7 billion board feet of lumber a year and supporting a million jobs. Then the economic crash of 1929 sent the nation’s economy into free fall. Not only timber, but fishing, farming, and mining—the extractive industries that were the backbone of the coastal economy—suffered from plummeting markets, as the nationwide malaise curtailed industrial production and domestic spending. Between 1929 and 1932, lumber exports were cut in half, and the salmon pack declined by 120 million pounds. Employment in production industries dropped by more than one-third: for every one hundred Oregon workers who had been employed in 1929, there were sixty-three in 1933.

The Oregon Coast, and indeed the whole state, became a place of idled mills, mines, and factories; unemployed workers; and families in need. Some Oregonians left to seek their fortunes elsewhere, even as refugees streamed in from the Dust Bowl, where the suffering was even more dire. An estimated ten thousand families came to the Northwest from the parched Great Plains in 1936. Still, for every three who came to Oregon, two left.

Tax delinquencies soared. By 1936, Oregon landowners were delinquent on $40 million in taxes. Huge acreages of timberlands reverted to counties, as their owners walked away rather than pay the taxes. The question of what to do with these lands set up a sequence of events that would propel the state of Oregon into the land and timber business in 1948, when Oregon passed a controversial bond issue to reforest the Tillamook Burn.

The Tillamook Burn began with a forest fire in August 1933, purportedly touched off by a careless logging operator. The fire, fanned by a hot east wind, burned 240,000 acres of mostly virgin Douglas-fir forest—an area one-third the size of Rhode Island—in Tillamook and Clatsop Counties on the northwestern Oregon Coast. Three more fires—in 1939, 1945, and 1951—left a massive blackened landscape and caused people to wonder if they would ever see trees growing in the Tillamook country again. Salvage operations, begun almost before the embers were cold, recovered a substantial fraction of the trees that were charred but not consumed. But what was to be done with the burned land?

Public concern over the fate of the Tillamook Burn led Governor Earl Snell to appoint a citizens’ committee to study the question. The committee recommended a huge reforestation effort, bigger than any ever tried, to restore the area to its “natural, wealth-producing status” and to turn it into “a 300,000-acre growing tree farm” in the words of one newspaper account.

Much of the burned land was owned by Tillamook and Clatsop Counties, delivered into their hands by owners who had defaulted on property taxes during the Depression. To accomplish the reforestation, the Oregon Department of Forestry proposed a deal: the counties would deed the land to the State of Oregon, and state foresters would rehabilitate the Burn. The payoff was the money that would eventually come to county coffers from logging the mature forest.

The controversial idea was not popular in Tillamook County, which might have expected to benefit the most. Nevertheless, with the help of a successful statewide vote on a bond issue in 1948, the reforestation effort became reality. Soon after the passage of the measure, Portland Public Schools, the Board of Forestry, and various businesses and civic organizations arranged for schoolchildren to assist in the replanting efforts. Between 1950 and 1970, more than twenty thousand schoolchildren participated in the Tillamook Burn Replanting Project. Proponents of the program believed that it taught future generations about forest conservation and built citizenship skills. By the early 1960s, the Tillamook was cloaking itself again in green.

Governor Tom McCall dedicated the new Tillamook State Forest in July 1973 with these words: “More than a million snags are gone...and in their place is a new stand of Oregon’s economic life blood. The trees will grow, and suffer our harvest, and grow again. The forest...again will feed us.”

The Tillamook is not Oregon’s first state forest—that distinction belongs to the Elliott State Forest near Coos Bay—but the unusual circumstances of its creation opened a new role for the state of Oregon in owning and managing timberlands. Since the 1970s, trees in the Tillamook State Forest have grown tall even as public enthusiasm about the commodity use of timber has cooled. State foresters, who have struggled to develop a balanced plan for the Tillamook and Clatsop state forests, now find themselves in a tug of war between the forest-products industry and county officials, who push for more logging, and environmentalists, who would prefer that the Tillamook State Forest be mostly reserved from logging.

Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

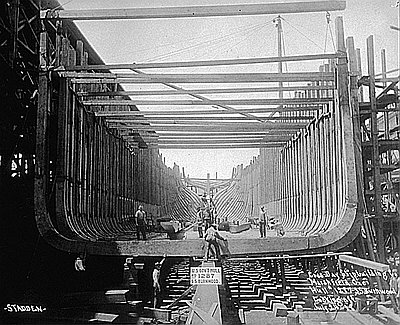

Shipbuilding, World War I

The shipyards at Grant-Smith-Porter Ship Co. still show considerable activity just after WWI. Wartime shipbuilding provided a bright exception to Portland’s otherwise lackluster economy during the First World …

Earl Snell (1895-1947)

This photograph of Earl Snell was taken in 1947. Snell served as Oregon’s secretary of state from 1934 to 1942 and as governor from 1942 to 1947. Earl …

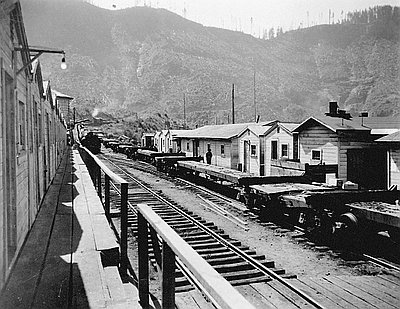

Salmonberry Burn, 1945

This photograph was taken in July 1945. It shows Governor Earl Snell looking on as State Forester Nelson Rogers describes the 5,000-acre Salmonberry fire. This blaze was one …