The southern Oregon Coast between Coos Bay and Gold Beach experienced an early and mostly unproductive mid nineteenth-century gold rush, which gave Gold Beach its name. The gold fever started in the winter of 1853, when hopeful panners flocked to the black sands of Whiskey Run Creek south of Coos Bay. Within a few weeks, a raggle-taggle town called Randolph had sprung up along the shoreline. According to a pioneer history of the area, “Miners, up from the sluices on the beach, warmed chilled bones in improvised saloons, the steam from their sodden garments mingling with the reek of whiskey, wood smoke and kerosene....against a somber background of densely-wooded hills, sprawled the town, a jumble of board and log houses with shake roofs, stone and mud chimneys, oiled-paper windows, and puncheon floors.” Randolph was washed away in a storm in the spring of 1854. Before long, someone made a strike farther up in the hills on a tributary of the Coquille River, and Whiskey Run was drained of all but its most dogged prospectors.

While mining for gold along the south coast never amounted to much, coal became an early and important industry. Coos Bay’s first coal was mined in the early 1850s, and the earliest shipments went to San Francisco in 1854. The first mines were small and locally owned, but by the 1870s most were owned by outside entrepreneurs.

The Beaver Hill mine at the head of Beaver Slough south of Coos Bay and the Newport-Libby mine on South Slough, named for the daughter of a Coos headman who lived nearby, were early successful mines in Coos County. These and other coal mines encountered hard times in the mid 1880s, when large quantities of coal came into San Francisco as ballast for ships. The coal was dumped onto the market and sent prices down. Miners at the Libby mine went on strike, closing the operated for weeks and bringing the company to its knees. Eventually, it was foreclosed and purchased by another owner. The Henryville mine on Isthmus Slough, also financed by San Francisco money, was called “the most colossal coal mining venture in Coos County to hang on for many years with never a penny of profit,” according to a 1952 history of Coos and Curry Counties.

In coal’s heyday, the Coos Bay area had seventy-four mines, prospects, and undeveloped outcrops. The value of Coos Bay coal exports in 1876-1877 was more than $300,000, and the industry employed several hundred miners. It also gave rise to a number of ephemeral towns, including Beaver Hill and Libby. Beaver Hill was incorporated in 1896 with eighty-five registered voters on the poll book. When the town’s citizens voted to disincorporate in 1926, only sixteen voters were left; fifteen of them voted in favor of disincorporation. The town then vanished from the landscape, to be succeeded by second- and third-growth Douglas-fir plantations. The coal industry around Coos Bay lasted until the coal market started to wane in the 1920s, although at least one mine was still operating in 1953.

Perhaps more than anything else, lumber has been the economic mainstay of the Oregon Coast, as well as its cultural hallmark. Most new settlers along the coast felled their own trees and sawed their own lumber, although some lumber was imported by ship from San Francisco. The 1849 California gold rush sent the lumber market into a boom, and sawmills sprang up all over western Oregon. In the spring of 1848, eighteen water-powered sawmills were operating on the Willamette and lower Columbia; three years later, Oregon had one hundred sawmills. Even before the mining boom, the export market made a difference in local prices. A newspaper article reported in 1848: “Oregon lumber is shipped to California and the Sandwich [Hawai‘ian] Islands—and its value for shipment controls its price at home.”

The first sawmill at the mouth of the Columbia opened in 1851 at Astoria, near the site of Fort Clatsop. The first on the South Coast was built at Port Orford in 1854 from parts brought in by steamship; another one opened on the Coquille River soon after. The Port Orford mill employed twenty-five men and had a capacity of five thousand board feet per day. The lumber, an aromatic wood of an unfamiliar species, was shipped green to San Francisco, where it brought $125 per thousand board feet. It came from a tree that grows bountifully along that small area of the southern Oregon coast but virtually nowhere else. One of the mill’s managers christened the tree Port Orford cedar.

The first sawmill in Coos County was built in 1853 or 1854 at Bullard’s Ferry (present-day Bullard’s Beach), north of the Coquille River. It had a “muley” sash saw (a saw with a reciprocating blade) powered by a water wheel. Logs were hauled to the mill by bull team, the first in Coos County.

A year or two later, two of the Coos Bay area’s most noted entrepreneurs, H.H. Luse and Asa Meade Simpson, raced each other to get their mills up and running—Luse’s at Empire City, Simpson’s at North Bend. Luse won the race. “Simpson might have won had the machinery not been delayed by the wrecking of the schooner Quadratus just after it had passed over the Coos Bay bar,” according to a 1952 local history. “Simpson reportedly made his first shipment to San Francisco in 1858; Luse in 1857.” Simpson went on to build mills at Gardiner, Port Orford, and Crescent City, California, as well as at Astoria and Knappton on the Columbia River and at Grays Harbor, Washington.

Steam power came to the coastal lumber industry in the 1850s, a few years behind Portland. In 1867, John Pershbaker built a steam sawmill and store on the Coos River estuary in the new town of Marshfield. J.C. Tolman named the town in 1854 after his hometown in Massachusetts. In 1873, a group of California businessmen, E.B. Dean and Co., built a sawmill in Marshfield that could handle fifty thousand board feet a day, more than the Luse and Simpson mills combined. E.B. Dean also built a shipyard and acquired extensive timberland holdings in the hills around Coos Bay.

Farther south, Bandon’s lumbering industry was slower to develop. Bandon was founded in 1874 by George Bennett, an Irish immigrant who named it after his hometown in County Cork. Bennett is also credited, or blamed, for importing a prickly, oily-sapped leguminous shrub, known in Ireland as furze and in Oregon as gorse. The shrub spread rapidly along the South Coast, and its presence in and around Bandon contributed to the devastation of the 1936 fire that swept in from the east and burned the town to the ground.

New York native Ralph Hewitt Rosa built Bandon’s first sawmill in 1883. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers then built two jetties at the entrance to the Coquille River harbor, giving Bandon access to markets in San Francisco and Portland. In 1896, the Coquille River lighthouse was built. Bandon became an exit port for milk, potatoes, coal, and other products from up the Coquille River and a point of entry for food and retail products from San Francisco.

With its port activity, three sawmills, two shipyards, a woolen mill, a creamery, and two canneries, Bandon enjoyed a spurt of growth at the turn of the twentieth century. The town’s population almost tripled between 1900 and 1910, increasing from 645 to 1,803 people. In 1909, the Moore mill burned down and was rebuilt, and a major fire destroyed the town’s waterfront business district in 1914.

The town of Brookings was created in 1913 by the Brookings Timber and Lumber Company, which owned mills and forestland in California. They bought some twenty-seven thousand acres of timberland between the Pistol and Chetco Rivers and built a sawmill on the Chetco’s north bank. To design their new town, the company hired California architect Bernard Maybeck, who rejected a rectilinear grid in favor of curving streets that followed the contours of the land. This and the designs he used for workers’ houses gave the town a pleasing appearance that was uncharacteristic of company towns.

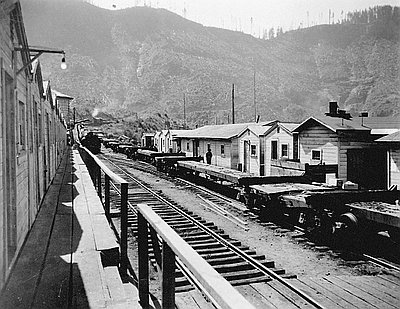

Despite a lull in the market in the 1860s, the timber industry continued to grow. By 1888, it was “the wheel which sets all other wheels in motion,” according to the Oregonian. Six or seven large sawmills on the lower Columbia exported a combined 75 to 100 million board feet of lumber a year during the 1880s and 1890s.

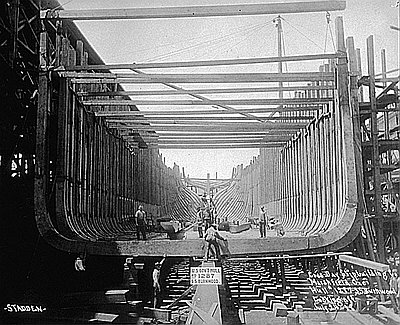

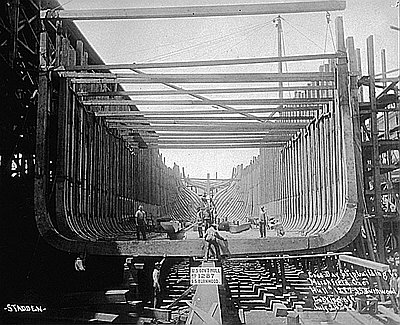

All early industries on the coast depended on water transportation to move goods to markets. Shipbuilding became a major industry along Coos Bay, the largest deep-water harbor between Seattle and San Francisco. The natural harbor and the ready availability of timber attracted early infusions of both capital and skilled immigrant labor to build ships. The concurrent discovery of coal in marketable quantities helped push the south coast’s shipbuilders into the steam age and strengthened the shipping capacity that later allowed Coos Bay to boast that it was the largest lumber-shipping port in the world.

This early constellation of natural resources, money, and muscle set the south coast on its path of becoming a supplier of raw materials to the rest of the world. It also ensured that the sea, not the interior, would be the area’s most important gateway to the outside world until the railroads arrived in the early twentieth century.

Lumber entrepreneur Asa Meade Simpson started the bay’s first shipyard in North Bend in the late 1850s and the first ship launched from the yard was the 103-foot brig Arago in 1859. By the time Simpson’s yard closed in 1902, it had produced fifty-eight sailing ships. Many of them were used for transporting Simpson lumber out of the bay, but not all. Danish master shipbuilder John Kruse, for example, built the graceful three-masted barkentine Tropic Bird for Simpson in 1882 for the South Sea Islands trade between San Francisco and Tahiti.

Simpson’s most famous ship was the three-masted brig Western Shore, also built by Kruse and considered to be the only true clipper ship built on the West Coast. In 1876, the Western Shore sailed from Portland to Liverpool in 101 days, one of several record-breaking voyages. The Western Shore's fame lasted longer than she did: she was wrecked on Duxbury Reef, north of San Francisco, in 1878.

The last sailing ship produced in the Simpson yard was the Marconi, launched in 1902. After many successful voyages, the Marconi ran aground in 1909 on the south end of Coos Bay’s North Spit, bound for Valparaiso with a full load of lumber. Much of the lumber was salvaged and used to build the Shore Acres estate of Louis B. Simpson, Asa Simpson’s son, a couple of miles down the coast.

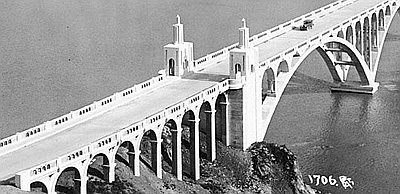

Around the turn of the twentieth century, with the help of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, cities with harbors began to develop their port facilities by building jetties, dredging, and deepening shipping channels.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.