The pioneers who went west in the mid-nineteenth century found the Willamette Valley “about as Edenic as they had expected,” wrote Terence O’Donnell. The hundred-mile-long valley, a lush oak savannah, offered berries, hazelnuts, and other provisions; timber for houses; and ideal homesteading opportunities. The folk traditions that many carried with them from New England and the Midwest reflect the northern European roots of early U.S. settlement. Those “webfoots” who settled in the Willamette—so-called by the California miners in sunnier climes—bequeathed cultural forms that linger today as traces of a pioneer resourcefulness: quilts from scraps, woven willow baskets, hand-carved chairs and furniture, and vernacular housing styles that resembled their kindred structures in the Midwest and New England. The new settlers found indigenous cultures in the valley that predated their own arrival by thousands of years. Many settled in Portland as workers in the lumber and flour mills or as traders when this port city boomed after its 1851 incorporation.

In the twenty-first century, Oregon grows more diverse each year. In Portland’s schools, loudspeakers blare announcements in Russian, Spanish, and Vietnamese. In what was for a time a predominantly Caucasian Willamette Valley, one in four residents claims a racial identity other than white. Thirty-three languages are spoken in Oregon, most of them in the Willamette Valley. In Washington County, 23.3 percent of the population speaks a language other than English at home, including Spanish, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Korean. In Multnomah and Clackamas County households 19.6 percent and 11.8 percent respectively speak a language other than English, primarily Spanish, Russian, or Chinese. Though the indigenous population lost land, along with many material objects and cultural practices, Native Americans in the Willamette Valley today form a vital community.

Imagine you are a newcomer exploring the folklife at the mouth of the Willamette River in Portland, a place nicknamed for its most abundant flower. At a downtown office, political jokes fly around the water cooler as people into work. As folklore, jokes allow us to express what we cannot otherwise talk about—sex, natural disasters, and human foibles. Many jokes use artful phrasing, building metaphorically on folk speech such as “he’s not the sharpest knife in the drawer.” While jokes often pass word of mouth, they also move as what is known as xeroxlore in photocopies and emails, all outside the official world of work. What marks these as folk traditions is their communication of community beliefs or values.

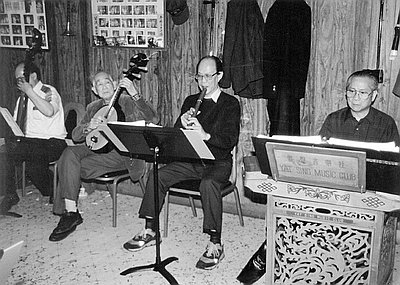

In the evening, the Yat Sing Music Club is warming up in a Chinatown restaurant. Most members are restaurant workers who learned in China to play the butterfly harp, hammer dulcimer, violin, or pe-pei for traditional Cantonese opera. The club formed in the 1940s to raise money to send to China’s war against Japan. The group performs for weddings and Chinese New Year events, their traditions reshaping to accommodate a new generation of bicultural Chinese Americans.

For years, on Northeast 103rd and Glisan Street, a sewing circle has met twice a month, sponsored by the Arts for New Immigrants Program at the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization. Women from all over the world have gathered to sew, knit, weave, and talk in Swahili, Arabic, Bosnian, French, Spanish, and English. They might discuss daughters’ schooling, sons’ weddings, or where to buy Mexican beans or Zimbabwean grains in their adopted home. Many of the group’s members came from cultures where women’s roles are less public than men’s, underscoring gender as a critical element in understanding folklife.

In Portland’s schools, a plentitude of languages are spoken and traditional arts featured. A Chinese immersion program was started at Woodstock Elementary School, and Shanghai-born Jean Qui Ye taught calligraphy, brush painting, paper cutting, and Chinese at the Spring Leaf Chinese Language School. Arts-in-education programs have featured such artists as Palestinian Feryal Abassai Ghnaim, who discovered after she moved to the United States that the traditional embroidery she had learned from her mother and grandmother were important to her identity. She arrived at a class in a floor-length dress embroidered with small red “missiles,” a design her mother used to express her resistance to British weapons in Palestine. For Feryal, folk arts were not “quaint and rural” or unrelated to social issues. While living in Massachusetts, she worked on a project called “A Passion for Life” through which Jewish and Palestinian women shared needlework and stories. Through the sharing of their arts, these traditional enemies became friends. As Feryal says, “Once you’ve heard their stories, how can you hate?”

On first Thursdays in Portland, galleries open late. The exhibits have included an Asian arts show at the Contemporary Crafts Gallery, featuring colorful Chinese rod puppets. An art form that dates back to the sixth-century B.C.E. in China, puppeteers taught children and conveyed news to the community. Yuqin Wang, a master puppeteer, and her husband Zhengli “Rocky” Xu, puppet maker and designer, are part of Dragon Art Studios. In 2004, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded the group a National Heritage Award.

On Friday nights, many in Portland’s Jewish community have a Shabbat to honor the Sabbath, which in Hebrew means “to cease.” Friday night at sunset often begins with a special meal and the lighting of Shabbat candles. Most of Portland’s Jewish community is Eastern European or Ashkenazi Jews, though some are Sephardic Jews, of Mediterranean origin. Others may come from Ethiopia, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Kurdistan, or central Asia. The Portland Jewish Academy and other community centers teach oral tradition, music such as Klezmer—the Yiddish word for “performing musician”—and rituals of Jewish life.

You might not think to look for folklife under the Morrison Bridge that crosses the Willamette River to link downtown Portland with the eastside industrial district. Teenagers riding skateboards under the bridge share a particular clothing style (extra-large t-shirts, baggy shorts, and backward baseball caps), identity (counter-authority), spaces (knowledge of sites such as bridge underpasses spread by word of mouth and in secret), material arts (painting their boards), and performance (the skating itself). On one hand, skateboarders are pop-culture icons; on the other, their work may appear in art museums. At heart, they are a folk group creating a culture of resistance. Like many communities at the edge, skateboarders offer insight into mainstream culture.

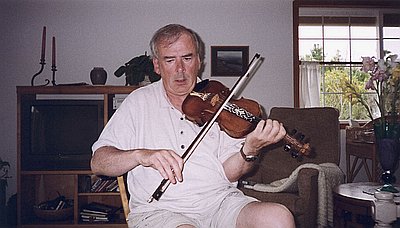

On Saturday nights, music fills the city’s clubs, streets, and concert halls. Any of those venues might support folk music, as the context for “folk” can shift. Internationally acclaimed Irish fiddler Kevin Burke, for example, might play at the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall or in a local bar. Burke, who received a National Heritage Award in 2002, was born and raised in London in a family originally from County Sligo in Ireland. When he settled in Portland, he was already widely recognized.

Sunday mornings give rise to quieter but equally vital musical traditions in Portland. There are a range of meeting places, including Catholic and Protestant churches and Mormon and Buddhist temples. Gospel music resonated from the Mount Olivet Baptist or Emmanuel Temple Church in north Portland. Gospel music emerged in the early twentieth century, when blues and jazz transformed traditional hymns and spirituals. In Portland, as in other communities, debate revolves around the proper place for gospel. Sacred feelings and strong voices follow singers from Mt. Olivet and other churches to the GospelFest at the secular Rose Festival each June.

Spiritual life is not relegated to Sabbath observance. Each religious group offers guidance for how to live. Spiritual practices are an essential aspect of folklife, often combining institutional and folk versions. Anthropologist Robert Redfield contrasted two types of traditions: “great”—the classical forms often associated with literacy, elites, and cities—versus “little”—vernacular, often oral forms associated with villages and neighborhoods. Mexican and Mexican-American women command the “little” tradition of altaristas (home altars) for their expressions of faith and cultural heritage. Often, el niño Jesus or La Virgen de Guadalupe forms the altarista’s center surrounded by votive candles, flowers, and images of family. There, women pray for health, family, and community—a direct communication outside churches.

For the Hmong community, qeej (pronounced gaeng) musicians similarly speak directly to the spirits through this reed wind instrument of bamboo pipes joined by a wooden chamber. Originally from China, the Hmong migrated to Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand to escape political oppression. Many arrived in Portland after 1975 when the U.S.-supported Royal Lao government collapsed. Yie Hue Vang is a qeej master, communicating with the other world about the soul of the deceased at funerals; without such intervention, the dead cannot trace their ancestral roots to find a resting place. Beliefs about life and death vary tremendously from culture to culture, finding form in folk arts and folklife. Different approaches to death underscore how essential and how “naturalized” our rituals and practices become.

© Joanne B. Mulcahy, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014